By Christopher Alessi

Imagine an elevator that moves without attached cables, and can

travel horizontally or vertically, sharing a shaft with several

other cabs.

That is the vision of German industrial conglomerate

Thyssenkrupp AG, which aims to use magnetic-levitation technology

to revolutionize a business that has essentially delivered the same

product for over a century.

Thyssenkrupp hopes by adapting maglev technology used in

high-speed trains, it could elbow aside rivals including United

Technologies Corp.'s Otis unit, the world's largest and oldest

elevator maker.

Otis and Thyssenkrupp's two other global competitors, Finland's

Kone Corp. and Switzerland's Schindler Group, are taking

incremental approaches to innovation for their people-movers.

Kone offers carbon-fiber elevator cables that have higher

tensile strength than traditional metal, permitting taller shafts.

Otis and Schindler have focused on improving the computers that

manage how banks of elevators operate, seeking to cut passengers'

waiting times and improve efficiency. Thyssenkrupp offers similar

systems.

Only the storied German steel and engineering company is

proposing to eliminate the elevator cable altogether, fashioning a

kind of hyperloop for commercial buildings. Thyssenkrupp already

runs a scaled-down mock-up and later this year aim to demonstrate a

full-size working prototype. If all goes well, sales could begin as

soon as next year.

"It will definitely take some years to filter through, but it's

a start, " said Andreas Schierenbeck, chief executive of

Thyssenkrupp's elevator division. He predicted the technology,

dubbed Multi, would ultimately make elevators faster and more

efficient while transforming the way buildings are constructed.

Rivals are skeptical.

"So far, these kinds of concepts have not been commercially

viable," said Kone Chief Executive Henrik Ehrnrooth.

Silvio Napoli, Schindler's former chief executive and now a

director, said horizontal elevator concepts are "not that new for

the industry."

"Competitors were working on this years ago but found problems,"

including high energy consumption, he said.

Otis in the 1990s designed a system to run both vertically and

sideways, but its intricate system of pulleys and cables proved too

complex to install, according to Dario Trabucco, a researcher at

the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, a nonprofit

standards organization.

Otis declined to comment for this article.

James Fortune, an expert at Fortune Shepler Saling Inc., an

elevator consultancy that works with developers and architects,

said Thyssenkrupp's biggest challenges will be "to develop a

working system that would be cost-competitive" and to convince

developers they should take the risk of using its unique and

proprietary system.

Today's high-speed single elevators typically cost between

$400,000 and $600,000 a shaft, he said. A Thyssenkrupp spokesman

said pricing estimates for Multi aren't yet available but "the

savings in reduced footprint for super-tall and mega-tall buildings

is enormous and pays off easily."

Replacing an installed elevator system could cost millions of

dollars, and in some structures could be impossible. So developers

shun risk.

"This will be a very niche market," said Andre Kukhnin, an

equity analyst at Credit Suisse, noting that buildings would need

to be designed entirely around Thyssenkrupp's system. Mr. Kukhnin

said an evolutionary technology like Kone's carbon-fiber rope may

have a bigger impact on the industry.

Kone's Mr. Ehrnrooth said its synthetic belts, which are already

in use, are much lighter than traditional steel cables, so its

system consumes less energy and costs less to maintain. Kone says

its "UltraRope" will allow elevators to double today's maximum

shaft height of about 500 meters.

Longer shafts reduce the need for elevator transfer lobbies on

high floors, boosting rentable space, experts say.

Still, Thyssenkrupp's Multi is the first big break from cables

in 160 years. Rather than operating like a yo-yo, it hovers each

cab vertically or horizontally with magnetic fields.

Floating up a tower might make some elevator riders skittish but

the average passenger is "absolutely ignorant" about how elevators

work, said Mr. Trabucco at the Council on Tall Buildings. Enticing

riders shouldn't be hard if the system is fast, he said.

Thyssenkrupp said it is still developing safety features in

coordination with consultants and building developers. It said all

Multi elevators will employ a "multistep braking system" to handle

"all possible scenarios of operation."

Thyssenkrupp started actively developing the technology in the

1970s with German engineering group Siemens AG for a high-speed

train project that was canceled in Germany, though one of their

Transrapid trains runs in Shanghai.

"But the technology is there...the patents are there," said

Thyssenkrupp's Mr. Schierenbeck. Rivals, he noted, "don't have

access to that technology."

Albert So, an elevator expert at the Asian Institute for Built

Environment, predicted magnetic-levitation elevators would

eventually spread because it is the only available technology that

could allow more than two cars in a shaft. Such sharing would

significantly boost efficiency.

Thyssenkrupp since 2003 has offered a more traditional cable

system that runs two independent cabins in one shaft. The system

ensures the cars stay safely separated. It operates in several tall

buildings, including the new European Central Bank headquarters in

Frankfurt.

Write to Christopher Alessi at christopher.alessi@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

July 18, 2016 17:17 ET (21:17 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

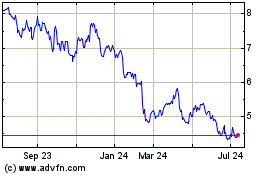

Thyssenkrupp (PK) (USOTC:TKAMY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jun 2024 to Jul 2024

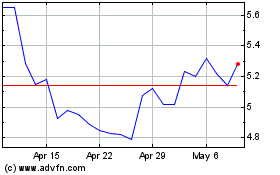

Thyssenkrupp (PK) (USOTC:TKAMY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jul 2023 to Jul 2024