false

0001472012

0001472012

2024-02-13

2024-02-13

iso4217:USD

xbrli:shares

iso4217:USD

xbrli:shares

UNITED STATES

SECURITIES

AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

Washington, D.C.

20549

FORM 8-K

CURRENT REPORT

Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d)

of the

Securities Exchange Act of 1934

Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported):

February 13, 2024

Immunome,

Inc.

(Exact name of registrant as specified in its

charter)

| Delaware |

|

001-39580 |

|

77-0694340 |

(State or other jurisdiction

of incorporation) |

|

(Commission

File Number) |

|

(IRS Employer

Identification

No.) |

665

Stockton Drive, Suite 300

Exton, Pennsylvania |

|

19342 |

| (Address of principal executive offices) |

|

(Zip

Code) |

Registrant’s

telephone number, including area code: (610)

321-3700

Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K

filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions:

| ¨ | Written

communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) |

| ¨ | Soliciting

material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) |

| ¨ | Pre-commencement

communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) |

| ¨ | Pre-commencement

communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) |

Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b)

of the Act:

| Title

of each class |

|

Trading

Symbol(s) |

|

Name

of each exchange

on which registered |

| Common

Stock, $0.0001 par value per share |

|

IMNM |

|

The Nasdaq

Capital Market |

Indicate by check mark

whether the registrant is an emerging growth company as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act of 1933 (§230.405 of this chapter)

or Rule 12b-2 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (§240.12b-2 of this chapter).

Emerging growth company x

If an emerging growth

company, indicate by check mark if the registrant has elected not to use the extended transition period for complying with any new or

revised financial accounting standards provided pursuant to Section 13(a) of the Exchange Act.

| Item 2.02 |

Results of Operations and Financial Condition. |

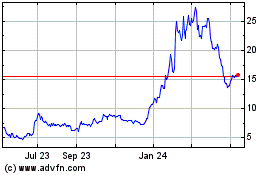

On February 13, 2024, Immunome, Inc.

(the “Company”) announced the commencement of an underwritten public offering of its common stock (“the Offering”).

The Company will file with the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) a preliminary prospectus supplement (the “Preliminary

Prospectus Supplement”) to its automatic shelf registration statement on Form S-3 (which was filed earlier today with the SEC)

pursuant to Rule 424(b)(5) under the Securities Act of 1933, as amended (the “Securities Act”), relating to the

Offering. The Company will include the following disclosure in the Preliminary Prospectus Supplement:

“Based upon preliminary estimates and information available to us as of the date of this prospectus supplement, we expect to report that

we had approximately $138.1 million of cash, cash equivalents and marketable securities as of December 31, 2023.”

Our actual financial statements as of and

for the year ended December 31, 2023 are not yet available. The actual amounts that we report will be subject to our financial closing

procedures and any final adjustments that may be made prior to the time our financial results for the year ended December 31, 2023

are finalized and filed with the SEC. Our independent registered public accounting firm has not audited, reviewed, compiled, or applied

agreed-upon procedures with respect to the preliminary financial data. This estimate should not be viewed as a substitute for financial

statements prepared in accordance with accounting principles generally accepted in the United States and it is not necessarily indicative

of the results to be achieved in any future period.

The information in this Item 2.02 shall not

be deemed “filed” for purposes of Section 18 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended (the “Exchange

Act”), or otherwise subject to the liabilities of that section, nor shall it be deemed incorporated by reference in any filing under

the Securities Act or the Exchange Act, except as expressly set forth by specific reference in such a filing.

The Company is filing

certain information for the purpose of updating descriptions of the Company’s business and risk factors contained in the Company’s

other filings with the SEC. Copies of the additional disclosures are attached as Exhibits 99.1 and 99.2 to this report and incorporated

herein by reference.

Item 9.01 Financial Statements and Exhibits.

(d) Exhibits.

This Current Report on

Form 8-K contains forward-looking statements about the Company and its industry that involve substantial risks and uncertainties.

All statements other than statements of historical facts contained in this report, including statements regarding the Company’s

expectation that its pending asset acquisitions will close and, if closed, will complement the Company’s development pipeline, the

expected benefits of pending asset acquisitions, the Company’s strategy, future financial condition, future operations, research

and development, planned clinical trials and preclinical studies, technology platforms, the timing and likelihood of regulatory filings

and approvals for the Company’s product candidates, its ability to commercialize its product candidates, the potential benefits

of collaborations, projected costs, prospects, plans, objectives of management and expected market growth, are forward-looking statements.

In some cases, you can identify forward-looking statements by terminology such as “aim,” “anticipate,” “assume,”

“believe,” “contemplate,” “continue,” “could,” “design,” “due,”

“estimate,” “expect,” “goal,” “intend,” “may,” “objective,” “plan,”

“positioned,” “potential,” “predict,” “seek,” “should,” “target,”

“will,” “would” and other similar expressions that are predictions of or indicate future events and future trends,

or the negative of these terms or other comparable terminology.

The Company has based

these forward-looking statements largely on its current expectations and projections about future events and financial trends that the

Company believes may affect its financial condition, results of operations, business strategy and financial needs. These forward-looking

statements are subject to a number of known and unknown risks, uncertainties and assumptions described in the Company’s filings

with the SEC, including the section titled “Risk Factors” in Exhibit 99.2 attached to this report. Moreover, the Company

operates in a very competitive and rapidly changing environment. New risk factors emerge from time to time, and it is not possible for

the Company’s management to predict all risk factors nor can the Company assess the impact of all factors on its business or the

extent to which any factor, or combination of factors, may cause actual results to differ materially from those contained in, or implied

by, any forward-looking statements.

In light of the significant

uncertainties in these forward-looking statements, you should not rely upon forward-looking statements as predictions of future events.

Although the Company believes that it has a reasonable basis for each forward-looking statement contained in this report, the Company

cannot guarantee that the future results, levels of activity, performance or events and circumstances reflected in the forward-looking

statements will be achieved or occur at all. You should refer to the section titled “Risk Factors” in Exhibit 99.2 attached

to this report for a discussion of important factors that may cause the Company’s actual results to differ materially from those

expressed or implied by the Company’s forward-looking statements. Furthermore, if the Company’s forward-looking statements

prove to be inaccurate, the inaccuracy may be material. Except as required by law, the Company undertakes no obligation to publicly update

any forward-looking statements, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise.

SIGNATURES

Pursuant to the requirements of the Securities

Exchange Act of 1934, the registrant has duly caused this report to be signed on its behalf by the undersigned thereunto duly authorized.

| |

|

IMMUNOME, INC.

|

| |

|

|

|

| Date: February 13, 2024 |

|

By: |

/s/ Clay Siegall |

| |

|

|

Clay Siegall, Ph.D. |

| |

|

|

President and Chief Executive Officer |

Exhibit 99.1

IMMUNOME’S BUSINESS

Overview

We are a biopharmaceutical company focused on the development of targeted

oncology therapies. We believe that the pursuit of novel or underexplored targets will be central to the next generation of transformative

therapies. For that reason, we pursue therapeutics that we believe have best-in-class or first-in-class potential. Our goal is to establish

a broad pipeline of preclinical and clinical assets which we can efficiently develop to value inflection points. To support that goal,

we pair business development activity with significant investment in our internal discovery programs.

Our pipeline is centered on three preclinical assets: IM-1021, a ROR1

ADC; IM-4320, an anti-IL-38 immunotherapy candidate; and a currently undisclosed candidate that is a FAP radioligand therapy, or RLT,

candidate. We anticipate submitting investigational new drug applications, or INDs, for each of these programs in the first quarter of

2025. We are not aware of any active development programs targeting IL-38 and believe that IM-4320, if successfully developed and approved,

would be a first-in-class immunotherapy. We believe that each of these drugs has the potential to improve outcomes for patients across

multiple indications.

On February 5, 2024, we signed a definitive asset purchase agreement

to acquire AL102, an investigational gamma secretase inhibitor, or GSI, currently under evaluation in a Phase 3 trial for the treatment

of desmoid tumors. We expect the purchase of AL102 (which also includes AL101, a related asset) to close in late Q1 or early Q2 2024.

Following the closing of that deal, we will become a clinical stage company. Based on our evaluation of Phase 2 data, we believe that

AL102 has the potential, if approved, to establish a new standard of care for patients with desmoid tumors.

Immunome’s business model is built upon our expertise in discovering

and developing targeted therapies as well as its ability to evaluate and acquire high-potential assets. We believe that the successful

track record of the leadership team will make the Company more attractive to companies selling assets, especially early-stage biotechnology

companies that lack resources to efficiently develop their assets.

Our perspective is that the most important considerations when acquiring

an asset are the quality of its preclinical or clinical data and the economic terms it can be acquired on. Accordingly, we are willing

to consider assets across multiple modalities, including antibody drug conjugates, or ADCs, RLTs, naked antibodies, small molecules and

more. We believe that effectively pursuing a novel target requires selecting a modality that is appropriate to the target biology.

At present, our internal discovery efforts are centered on ADCs and

RLTs. We believe that a broad toolbox of linkers and payloads is necessary to design and develop a broad pipeline of ADCs, as different

targets may require different payloads to achieve optimal efficacy and therapeutic index. The novel linker-effector unit we exclusively

licensed from Zentalis is an important component of this toolbox, and we have efforts underway to develop additional linkers and payloads.

We also believe that the incorporation of albumin binders into radioligand therapies provides a differentiated approach that can increase

the dose of radiation absorbed by patient tumors.

Immunome’s Discovery Platform utilizes proprietary hybridoma

technology to immortalize memory B cells isolated from oncology patient samples. This enables the production of sufficient quantities

of antibodies to perform high-throughput functional screening, allowing for the recognition of antibodies and targets whose role in cancer

was not previously appreciated. In January 2023, we announced an agreement with AbbVie under which AbbVie paid $30 million upfront

for access to up to 10 targets identified by the Discovery Platform.

Immunome is led by Clay Siegall, PhD, President and Chief Executive

Officer. Dr. Siegall previously served as CEO of Seagen, which he co-founded in 1997 and led for nearly 25 years. During his tenure,

Seagen earned FDA approvals for four cancer therapies. Pfizer purchased Seagen in December 2023. Dr. Siegall joined Immunome

in connection with Immunome’s acquisition of Morphimmune, a preclinical biotechnology company led by Dr. Siegall, in October 2023.

In addition to Dr. Siegall, three members of our current management

team joined Immunome from Morphimmune in October 2023. Jack Higgins, PhD, Immunome’s Chief Scientific Officer, held the

same role at Morphimmune, He was previously the Chief Development Sciences Officer at Molecular Templates, where he led discovery and

development efforts for multiple clinical candidates and co-invented the company’s Engineered Toxin Body platform. Bruce Turner,

MD, PhD, Immunome’s Chief Strategy Officer, held the same role at Morphimmune and previously founded several biotechnology

companies including Xanadu Bio and Gennao Bio. Max Rosett, Executive Vice President, Operations, and Interim Chief Financial Officer at

Immunome, served as Acting Chief Operating Officer at Morphimmune. Mr. Rosett previously served as Principal at Research Bridge Partners,

where he led Research Bridge Partners’ investment in Morphimmune’s Series A financing.

Bob Lechleider, MD, serves as the Chief Medical Officer of Immunome.

Dr. Lechleider was most recently the Chief Medical Officer of OncoResponse and previously worked with Dr. Siegall at Seagen,

where he was responsible for directing the development of early and late-stage portfolios. Phil Roberts, serves as the Chief Technical

Officer of Immunome. Dr. Roberts previously served as SVP, Technical Operations at Mirati Therapeutics, where he led the CMC development

of Krazati, Mirati’s first approved product. Sandra Stoneman, JD, serves as Chief Legal Officer of Immunome. She joined Immunome

from Duane Morris LLP, where she was an equity partner. Kinney Horn serves as our Chief Business Officer. He previously served in the

same role at Olema Oncology and spent more than 15 years at Genentech.

Immunome’s Pipeline

ROR1 ADC (IM-1021)

On January 8, 2024, we announced that we had entered into an exclusive,

worldwide license agreement under which we licensed from Zentalis ZPC-21 (now IM-1021), a preclinical-stage ADC targeting the receptor

tyrosine kinase like orphan receptor 1, or ROR1. ROR1 has an oncofetal expression pattern, with little or no expression in healthy tissue,

and is expressed on solid and liquid tumors. We believe ROR1 has been clinically validated as an ADC target through clinical trials of

a competitor ADC in multiple B-cell malignancies.

The expression pattern of ROR1 suggests that it may have clinical utility

as a therapeutic target in multiple solid and liquid tumor indications, including diseases with large patient populations and high unmet

need (Figure 1). However, the moderate-to-low expression and slow internalization of ROR1 present challenges to developing a successful

ADC for the treatment of ROR1-positive solid tumors. Our approach to overcoming these challenges is focused on pursuing development of

IM-1021, which incorporates an ROR1 antibody that is designed to promote internalization; uses a linker-payload combination that we believe

provides a potentially improved therapeutic index and may allow for higher clinical dosing; and contains a payload that is designed to

maximize the potential bystander effect and supports a drug-antibody ratio, or DAR, of 8.

IM-1021 incorporates a cleavable, undisclosed linker that is used to

conjugate a camptothecin derivative (a topoisomerase I inhibitor) to the ROR1 antibody via cysteine conjugation, and provides a DAR of

8. In preclinical studies, IM-1021 showed sustained tumor regression in a mouse model triple-negative breast cancer, or TNBC. In

this model, IM-1021 dosed weekly for three weeks at 2.5 mg/kg or 5.0 mg/kg demonstrated superior reductions in tumor volume compared

with the same respective dose of a competitor, vedotin payload ROR1 ADC, with no meaningful weight loss observed (Figure 2).

Figure 2. IM-1021 showed favorable activity and safety findings

in a TNBC mouse model

We expect to submit an IND for the IM-1021 program to the FDA in the

first quarter of 2025. Subject to obtaining an IND, our IM-1201 clinical strategy is designed to efficiently evaluate dose escalation

in patients with solid tumors or lymphoma, followed by potential expansion of the solid tumor clinical program into targeted indications,

potentially including non-small cell lung cancer, breast prostate, pancreatic, and gastric cancer, and expansion of the lymphoma program

into diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma. Concurrent with the dose escalation and expansion studies, we plan to conduct

non-clinical studies evaluating IM-1021 in combination with other therapies, particularly in B-cell malignancies, and to evaluate and

develop potential companion diagnostics that could help identify patients most likely to respond to IM-1021. Our strategy is to pursue

pivotal clinical studies in indications that have shown compelling clinical outcomes in earlier-stage trials, present significant commercial

opportunities, have the potential for enhanced outcomes using a companion diagnostic, and offer potential for accelerated approval.

177Lu-FAP Radioligand Therapy

Through our merger with Morphimmune, we acquired a FAP-targeted Lu-177

radiotherapy development candidate for the treatment of solid tumors. FAP, or fibroblast activation protein, serves as a tumor-specific

marker due to its broad expression on cancer associated fibroblasts. Cancer-associated fibroblasts are the most common tumor stromal cell,

with expression in 75% of solid tumors. Our FAP-Lu RLT candidate is designed to deliver radioactive 177Lu directly to FAP-expressing

cells, where the “bystander” effect of the radiation may target nearby tumor cells. We believe this RLT approach could overcome

the limitations, such as poor internalization and low expression on tumor cells, that make FAP an unsuitable target for ADCs.

Our FAP-targeted radiotherapy candidate has four functional domains:

| • | A small molecule FAP-specific ligand |

| • | A linker tuned to drive tumor-specific uptake |

| • | An albumin-binding domain to improve tumor retention |

| • | A chelator to deliver the radionuclide |

We have conducted preclinical studies demonstrating that incorporating

albumin binders into RLTs improved biodistribution and in vivo pharmacokinetic profiles. Strong albumin binding resulted in higher total

absorbed doses in tumor compared with liver and kidney (Figure 4) and also led to increased and prolonged FAP-RLT levels in serum when

administered intravenously (Figure 5).

We are evaluating a series of potential drug

candidates that explore options for each of the four domains in order to select the combination that we believe may be most likely to

deliver therapeutic benefits in cancer patients. Several candidates have shown substantial tumor regression in an animal model of

glioblastoma (Figure 6A), with no weight loss observed (Figure 6B).

We believe our growing body of preclinical

data for these candidates demonstrates desirable characteristics that support the further development of a FAP RLT. These preclinical

characteristics include sub-nanomolar affinity, high specificity, radiostability, superior dose retention and tumor absorbed dose, and

preclinical activity and tolerability.

We expect to submit an IND for this program to the FDA in Q1 2025.

Anti-IL-38 Immunotherapy (IM-4320)

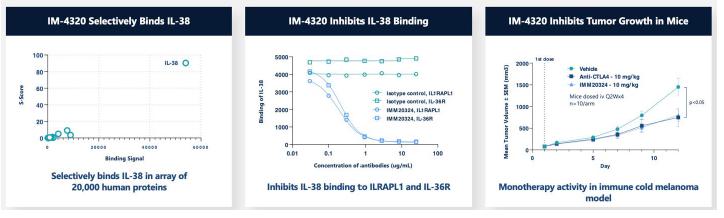

Our lead oncology program targets IL-38, which we believe is a novel,

negative regulator of inflammation capable of promoting tumor evasion of the immune system. IL-38 was identified as the target of an antibody

isolated from a hybridoma library generated from the memory B cells of a patient with squamous head and neck cancer.

Our query of public and proprietary databases of cancer gene expression

revealed over-expression of IL-38 in multiple solid tumors. Further, a correlation with low levels of tumor-infiltrating immune effector

cells, a hallmark of immune suppression in some of these patients’ tumors, and high IL-38 expression was also observed, suggesting

a role for IL-38 as an immune modulator.

Data obtained from preclinical testing showed that blocking IL-38 function

using inhibitory antibodies increased the immune response to the tumor and resulted in anti-tumor activity in select animal models, suggesting

that anti-IL-38 antibodies could have therapeutic utility as single agents or in combination with other therapeutic modalities. Our recent

analysis further showed IL-38 expression was frequently elevated in samples of select patient tumor subtypes, in cancers such as head

and neck, lung and gastroesophageal.

IM-4320 is our lead anti-IL-38 antibody. Our data indicates that IM-4320

bound to IL-38, inhibiting its binding ILRAPL1 and IL-36R. Furthermore, it inhibited tumor growth in an immune cold melanoma model. We

believe IM-4320 has shown preclinical activity consistent with an active immunotherapy agent.

We expect to submit an IND for this program to the FDA in Q1 2025.

AL102

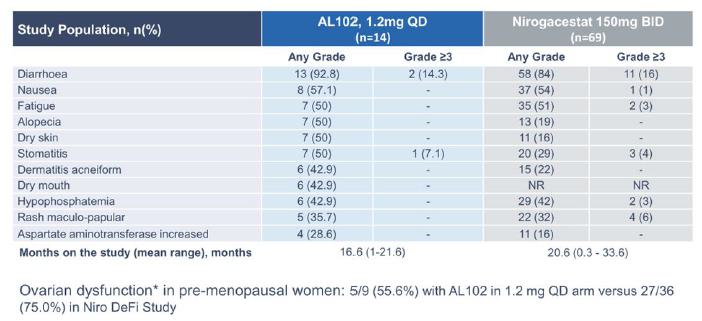

On February 5, 2024, we signed

an Asset Purchase Agreement with Ayala Pharmaceuticals, Inc. or Ayala, for AL102, a gamma secretase inhibitor, or GSI, currently

under evaluation in a Phase 3 trial for the treatment of desmoid tumors. We expect the purchase of AL102 (which also include AL101, a

related asset) to close in late Q1 or early Q2 2024.

Desmoid tumors are painful, aggressive

soft-tissue tumors that can lead to significant disability if left untreated. They are most commonly diagnosed in young adults, and they

are more common in women than in men. An estimated 1,000-1,650 patients are diagnosed with desmoid tumors each year in the US, and an

estimated 5,500 to 7,000 patients have desmoid tumors that are actively managed. In November 2023, OSGIVEO (nirogacestat) became

the first FDA-approved systemic treatment for desmoid tumors. Like AL102, nirogacestat is a gamma secretase inhibitor.

Our interest in AL102 was largely

a response to Phase 2 data, as shared by Ayala at ESMO in October 2023. Ayala’s data showed an objective response rate of 64%

in the intent-to-treat population and 75% among evaluable patients. Other measures of response including tumor volume, as measured by

MRI and cellularity as estimated via T2 imaging, also showed deep responses.

We believe the data published at

that time suggests that AL102’s safety results were similar to nirogacestat.

ADC Strategy

We are pursuing a target-driven development strategy intended to establish

a broad pipeline of next-generation ADCs focused on oncology indications with high unmet need. We are working to identify novel or under-explored

targets that we believe will enable the development of first-in-class ADCs. We also are working to identify clinically validated ADC targets

for which competitor programs have shown suboptimal efficacy and/or safety, with the goal of advancing best-in-class ADCs against these

targets that overcome these limitations. Our ability to achieve these goals is predicated on our deep understanding of ADC target biology

and our ability to deploy a broad toolbox of antibodies, linkers, and payloads in combinations that best match this biology.

Our development process is intended to efficiently advance ADC pipeline

candidates through clinical proof-of-concept. We believe that key steps in this process include:

| • | Optimize the antibody portion of the ADC for binding and internalization |

| • | Incorporate proven or novel linkers |

| • | Select payloads that provide consistent cytotoxic effects |

| • | Optimize ADC pharmacology for clinical activity |

| • | Enable early go/no-go decisions via well-designed clinical trials |

We believe that identifying appropriate targets is a key challenge

of ADC development. One piece of evidence for this is the concentration of current ADC development activity, with 54% of active ADC clinical

programs focused on the same ten targets (Figure 7).

We believe there are several downsides to pursuing these targets, including:

| • | Potential difficulty in overcoming limitations of existing ADCs against these targets due to heterogeneity of target expression on

tumor cells and/or the likelihood that changes in payload and/or linker technology will yield only incremental gains in efficacy. |

| • | Challenging development and commercialization pathways |

| • | Lower unmet patient need |

Given these downsides, we are systematically evaluating novel targets

that we believe will have first-in-class potential using multiple target and antibody sources. Our Immunome Discovery Platform (described

above) has already identified more than 30 novel targets and, subject to satisfaction of the closing terms of the definitive asset purchase

agreement with Atreca, Inc. announced December 26, 2023 (discussed below) we will have access to more than 25 antibodies that

may support the development of ADCs against novel or underexplored targets. We also screen public and proprietary expression databases

to identify other potential targets for ADC development. Potential targets identified through this systematic approach are evaluated for

differential expression on tumor cells compared with normal cells and additional factors.

We believe that our proprietary camptothecin derivative/topoisomerase

I inhibitor payload provides a significant opportunity to develop ADCs. This payload, which is in the same class as another camptothecin

derivative (deruxtecan) used in an FDA-approved ADC targeting HER2, was developed by Zentalis and is exclusively licensed by us. This

proprietary payload is designed to have enhanced ADME properties, including the potential for greater in vivo potency, increased

permeability that may lead to superior bystander effects, and faster clearance that may improve tolerability after cleavage. We have conducted

studies in the JIMT-1 breast cancer model demonstrating that a HER2 ADC constructed with our proprietary payload provided improved activity

compared with a deruxtecan-containing HER2 ADC when dosed intravenously weekly for three weeks.

We believe that camptothecin derivatives are well-suited for ADCs targeting

solid tumor because they achieve a higher DAR and higher clinical doses. Additionally, a third-party comparison of two FDA-approved HER2

ADCs that contain the same antibody (trastuzumab) but different payloads showed that percentage of patients with progression-free survival

was significantly higher for the ADC containing the camptothecin derivative.

In addition to our portfolio of targets, antibodies, and payloads,

we also have access to novel linker technologies under our exclusive worldwide license agreement with Zentalis (discussed below).

Immunome Discovery Platform

Immunome’s Discovery Platform provides a proprietary approach

to identifying cancer-associated targets. Although many of these targets are known in scientific literature, many of them were not previously

known to be associated with cancer.

The workflow for our platform is as follows:

Patient

Sampling: Our discovery process begins with obtaining a patient’s lymph node, tumor or blood sample

and then purifying and expanding the memory B cell population. In oncology, patients sampled include those who are treatment naïve,

treated with standard regimens, or have been treated with immunity enhancing therapies.

Patient

Response: We fuse and immortalize thousands of these patient-derived memory B cells using proprietary methods,

capturing them as hybridomas, each of which typically express an individual antibody in quantities sufficient for extensive functional

screening.

Antibody

Screening: For oncology, we screen individual antibodies by assessing their binding to intact cancer cells

or normal cells, or by assessing their binding to a large number of different extracts of authentic tumor samples and cancer cell lines.

Using our proprietary approach, we can screen up to 18,400 antibodies on a single array. Hybridomas producing antibodies that show both

high-affinity binding, by typically binding at single digit nanomolar concentrations, and specific binding, by showing much higher binding

to a subset of tumor cells compared to normal cells, are designated as screening “hits.” Hybridomas producing those hits can

be sequenced, their immunoglobulin genes can be cloned into expression vectors, and the individual antibodies can then be produced recombinantly.

Antibody

Validation: The next step in our process is to identify the specific antigen to which the antibody appears to bind with high

affinity and specificity. We use one of two complementary approaches for this activity: the first method involves an assessment of antibody

binding to known human proteins spotted on a protein microarray with high selectivity. If the target is not represented on the array or

no specific binding is seen, we attempt to use the antibody to “pull out” the antigen from its source using immunoprecipitation,

and then identify the antigen sequence using mass spectrometry. Using these two approaches we are largely successful in identifying the

antigen to which newly identified antibodies are binding. We then conduct experiments to assess whether the binding of the antibody to

the specific antigen can produce a change in the biology of a cancer cell expressing the target, which we refer to as target validation.

Additional tests, such as measurements of changes in cell growth, cell survival, cell migration, or internalization of the antigen after

it has been bound by the antibody, are used to further assess the potential that the antibody could be of therapeutic interest.

Strategic Transactions

Transactions Subject to Completion

Acquisition of Assets from Ayala Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

On February 5, 2024, the Company and

Ayala Pharmaceuticals, Inc., or Ayala, entered into an Asset Purchase Agreement, or the Ayala Purchase Agreement, pursuant to which

the Company will acquire Ayala’s AL101 and AL102 programs and assume certain of Ayala’s liabilities associated with the acquired

assets, or the Ayala Asset Purchase. Pursuant to the Ayala Purchase Agreement, at the closing of the Ayala Asset Purchase (the Closing),

the Company will (i) pay Ayala $20,000,000, subject to certain adjustments, (ii) issue Ayala 2,175,489 shares of Company common

stock, or the Ayala Shares, and (iii) assume specified liabilities. The Company is obligated to pay Ayala up to $37,500,000 in development

and commercial milestones.

Each

party’s obligation to consummate the Ayala Asset Purchase is subject to customary closing conditions, including the accuracy of

the other party’s representations and warranties as of the Closing, subject, in certain instances, to certain materiality and other

thresholds, the performance by the other party of its obligations and covenants under the Ayala Purchase Agreement in all material respects,

the Company’s receipt of the Stockholder Consents (defined below) from the Ayala stockholders with the requisite vote to approve

a sale of substantially all of the assets of Ayala and the lapse of at least twenty (20) calendar days from the date Ayala mails a definitive

information statement to its stockholders in accordance with Rule 14c-2 promulgated under the Exchange Act of 1934, as amended, receipt

of certain third party consents, the delivery of certain related ancillary documents by the other party, and the absence of any injunction

or other legal prohibitions preventing consummation of the Ayala Asset Purchase.

The Ayala Purchase Agreement also provides

that until the six-month anniversary of the Closing, Ayala will hold and not sell 50% of the Ayala Shares, subject to certain exceptions.

Further, Ayala has agreed, subject to certain exceptions, that until the one-year anniversary of the Closing, any transfer of the Ayala

Shares by Ayala that exceed 15% of the average daily trading volume of the Company’s stock over the five-trading day period ending

on the trading day immediately prior to such trading date shall be made pursuant to a block trade or other disposition through a market

participant designated by the Company.

The Company has agreed to use its commercially

reasonable efforts to (x) file a resale registration statement with the SEC registering the Ayala Shares for resale on or before

the date seven days following the earlier of (i) April 1, 2024 and (ii) the date the Company files its annual report on

Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2023 and (y) cause such resale registration statement to be declared effective

as soon as practicable after the filing thereof but no later than 90 calendar days after the filing thereof or by five trading days from

when the Company is notified that the SEC will not review the resale registration statement or that it will not be subject to further

review.

Acquisition of Assets from Atreca, Inc.

On December 22, 2023, the Company entered

into an asset purchase agreement with Atreca, Inc, or Atreca, pursuant to which the Company will acquire certain antibody-related

assets and materials for an upfront payment of $5.5 million and up to $7.0 million in clinical development milestones. The closing of

the transaction is subject to customary conditions, including the approval of Atreca’s stockholders.

Completed Transactions

Merger with Morphimmune

On October 2, 2023, the

Company completed its merger with Morphimmune Inc., or Morphimmune. Under the terms of the Agreement and Plan of Merger and Reorganization

dated as of June 28, 2023, or the Merger Agreement, among the Company, Morphimmune and Ibiza Merger Sub, Inc., a wholly owned

subsidiary of the Company, or Merger Sub, Morphimmune merged with and into Merger Sub, with Morphimmune surviving as a wholly-owned subsidiary

of Immunome, or the Merger. In connection with the Merger, on October 2, 2023, the Company issued and sold 21,690,871 shares

of its common stock pursuant to the subscription agreements in a Private Investment in Public Equity, or PIPE, transaction which provided

the Company with gross proceeds of $125.0 million.

Strategic Collaborations, License Agreements and Other Material

Agreements

We believe that our technology has broad utility and could enable us

to organically expand our pipeline by internal discovery. We are also dedicated to expanding our pipeline through disciplined mergers

and acquisitions. We believe our approach provides us the flexibility needed to maintain a pipeline of potential product candidates and

to maximize their value through internal development and strategic collaborations. The material asset collaborations, licensing and other

related agreements entered into by us to date are described in greater detail below.

License Agreement with Zentalis Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

In January 2024, the Company entered

into a license agreement, or the Zentalis License Agreement, with Zentalis Pharmaceuticals, Inc., or Zentalis, pursuant to which

the Company received an exclusive, worldwide, royalty-bearing, sublicensable license under certain intellectual property relating to Zentalis’

proprietary ADC platform technology, ROR1 antibodies and ADCs targeting ROR1 to exploit products covered by or incorporating the licensed

intellectual property rights. Under the Zentalis License Agreement, the Company is required to use commercially reasonable efforts to

develop an ADC targeting ROR1, two additional ADCs, and commercialize any product that has received regulatory approval.

Under the Zentalis License Agreement, the

Company paid to Zentalis upfront consideration totaling $35 million in cash and shares of Company common stock. The Company is obligated

to pay Zentalis up to $150 million in development and regulatory milestones for the first product containing an ADC targeting ROR1 (a

ROR1 ADC Product) to achieve such milestones and commercial milestones on ROR1 ADC Products. The Company is also obligated to pay to Zentalis

mid-to-high single digit royalties on ROR1 ADC Products. In addition, the Company is obligated to pay Zentalis $25 million in development

and regulatory milestones for the first product from each of the first five additional development programs using the licensed platform

technology to generate products, and mid-single digit royalties on products from each such program. The Company’s royalty payment

obligation will commence, on a product-by-product and country-by-country basis, on the first commercial sale of such product in such country

and will expire on the latest of (a) the ten (10)-year anniversary of such first commercial sale for such product in such country,

(b) the expiration of regulatory exclusivity for such product in such country, and (c) the expiration of the last-to-expire

valid claim of a licensed patent covering such product in such country.

The Zentalis License Agreement will continue

until the expiration of all royalty payment obligations. The Zentalis License Agreement may be terminated early by (a) either party

in its entirety upon (i) the other party’s uncured material breach, subject to a notice and cure period, (ii) any insolvency

event of the other party or (iii) prolonged force majeure, (b) the Company, either in its entirety or in part, for convenience

upon a specified period prior written notice, or (c) Zentalis (i) in its entirety if the Company challenges one of the licensed

patents or (ii) fails to meet certain development activity benchmarks within specified time periods.

Collaboration with AbbVie

On January 4, 2023, the Company entered into a collaboration and

option agreement, or the Collaboration Agreement, with AbbVie Global Enterprises Ltd., or AbbVie, pursuant to which the Company will use

its proprietary discovery engine to discover and validate targets derived from patients with three specified tumor types, and antibodies

that bind to such targets, which may be the subject of further development and commercialization by AbbVie. The research term is at least

66 months, subject to extension in certain circumstances by specified extension periods. Pursuant to the terms of the Collaboration Agreement,

with respect to each novel target-antibody pair that the Company generates that meets certain mutually agreed criteria (each, a Validated

Target Pair or VTP), the Company granted to AbbVie an exclusive option (up to a maximum of 10 in total) to purchase all rights in and

to such Validated Target Pair, for all human and non-human diagnostic, prophylactic and therapeutic uses throughout the world, including

without limitation the development and commercialization of certain products derived from the assigned Validated Target Pair and directed

to the target comprising such VTP (Products). No rights are granted by the Company to AbbVie under any of Company’s platform technology

covering the Company’s discovery engine. Until the expiration of the research term, the Company is not permitted to conduct any

activities in connection with targets or antibodies derived from patients with the specified tumor types, whether independently or with

other third parties, except in limited circumstances with respect to certain target-antibody pairs that are no longer subject to the collaboration

with AbbVie. In addition, during the term of the Collaboration Agreement, the Company is not permitted to develop products directed to

targets that are included in VTPs purchased by AbbVie, or to which AbbVie still has rights under the Collaboration Agreement, whether

independently or with other third parties.

Under the Collaboration Agreement, AbbVie will pay the Company an upfront

payment of $30.0 million, plus certain additional platform access payments in the aggregate amount of up to $70.0 million based on the

Company’s use of our discovery engine in connection with activities under each stage of the research plan, and delivery of VTPs

to AbbVie. AbbVie will also pay an option exercise fee in the low single digit millions for each of the up to 10 VTPs for which it exercises

an option. If AbbVie progresses development and commercialization of a Product, AbbVie will pay the Company development and first commercial

sale milestones of up to $120.0 million per target, and sales milestones based on achievement of specified levels of net sales of Products

of up to $150.0 million in the aggregate per target, in each case, subject to specified deductions in certain circumstances. On a Product-by-Product

basis, AbbVie will pay the Company tiered royalties on net sales of Products at a percentage in the low single digits, subject to specified

reductions and offsets in certain circumstances. AbbVie’s royalty payment obligation will commence, on a Product-by-Product and

country-by-country basis, on the first commercial sale of such Product in such country and will expire on the earlier of (a) (i) the

ten (10)-year anniversary of such first commercial sale for such Product in such country, or (ii) solely with respect to a Product

that incorporates an antibody comprising a VTP (or certain other antibodies derived from such delivered antibody), the expiration of all

valid claims of patent rights covering the composition of matter of any such antibody (whichever out of (i) or (ii) is later),

and (b) the expiration of regulatory exclusivity for such Product in such country. The Company is potentially eligible to receive

up to $2.8 billion from AbbVie under the Collaboration Agreement from the sources described above.

The Collaboration Agreement will expire upon the expiration of the

last to expire royalty payment obligation with respect to all Products in all countries, subject to earlier expiration if all option exercise

periods for all Validated Target Pairs expire without AbbVie exercising any option. In addition, the research term will terminate if AbbVie

does not elect to make certain platform access payments at specified points during the research term, in order for the Company to continue

the target discovery activities under the collaboration. The Collaboration Agreement may be terminated by (a) either party upon the

other party’s uncured material breach, or upon any insolvency event of the other party, (b) AbbVie for convenience upon a specified

period prior written notice, or (c) AbbVie for the Company’s breach of representations and warranties with respect to debarment

or compliance with anti-bribery and anti-corruption laws. If AbbVie has the right to terminate the Collaboration Agreement for the Company’s

uncured material breach or a breach of representations and warranties with respect to debarment or compliance with anti-bribery and anti-corruption

laws, AbbVie may elect to continue the Collaboration Agreement, subject to certain specified reductions applicable to certain of AbbVie’s

payment obligations (with a specified floor on such reductions).

Whitehead Patent License Agreement

In June 2009, we entered into an exclusive patent license agreement,

or the Whitehead Agreement, with the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, or Whitehead, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology,

or MIT, as licensing agent for Whitehead, pursuant to which we obtained from MIT and Whitehead a royalty-bearing exclusive license under

certain patent rights of Whitehead and a royalty-bearing non-exclusive license under certain biological and chemical material of Whitehead

that relate to our antibody screening platform, in each case to develop, manufacture, use, and commercialize licensed products and to

develop and perform licensed processes and perform licensed services for all purposes in the United States. The foregoing license grant

included the right to grant sublicenses with certain restrictions. Pursuant to the Whitehead Agreement, we are obligated to pay Whitehead

up to $725,000 in the aggregate for certain development, regulatory and commercial milestones and up to $275,000 for each product or derivative

that we discover using the licensed product or processes or Discovered Products. We are also obligated to pay Whitehead a low single digit

royalty on net sales of licensed products and licensed processes when sold as a therapeutic or diagnostic product, a mid-single digit

royalty on net sales of such licensed products or processes when sold as a research reagent, and a less than one percent royalty

on net sales of Discovered Products when sold as a therapeutic or diagnostic product. Our obligation to pay royalties on net sales of

Discovered Products is limited to a period of seven years from the first commercial sale of each Discovered Product. We are obligated

to pay Whitehead a high single digit royalty on service income received in connection with the provision of licensed services the provision

of which, absent the license granted under the Whitehead Agreement, would infringe a claim of a licensed patent. We are obligated to pay

Whitehead a high first decile percentage of certain payments received from sublicensees, subject to certain reductions to single-digit percentages,

and we are obligated to pay Whitehead a mid-teen percentage royalty on certain payments received from non-sublicensee corporate partners.

On November 17, 2022, the Company entered into a Letter Agreement,

or Letter Agreement, with Whitehead, which became effective on January 4, 2023, upon the satisfaction of the conditions described

therein. The Letter Agreement supplements the Whitehead Agreement. Pursuant to the Letter Agreement, Whitehead and the Company agreed

that certain payments received by the Company from the Collaborator (as defined in the Letter Agreement) (i.e., a corporate partner, as

defined in the License Agreement) would be excluded from the Company’s payment obligations to Whitehead. The Company and Whitehead

further agreed, among other things, that the Company will make certain payments to Whitehead (i) as Net Sales (as defined in the

License Agreement) as long as the Company receives those payments from the Collaborator on a specified number of products purchased by

the Collaborator and (ii) upon the achievement of certain milestones whether by the Company or the Collaborator.

We have the right to terminate the Whitehead Agreement upon specified

prior written notice to Whitehead. Whitehead may terminate the Whitehead Agreement in the event of our uncured material breach or insolvency.

Additionally, Whitehead may terminate the Whitehead Agreement if we or any of our affiliates or sublicensees challenges the validity,

patentability, enforceability or non-infringement of the licensed patents.

License Agreement with Purdue Research Foundation

In January 2022, Morphimmune entered into a Master License Agreement

(Purdue License Agreement) with Purdue Research Foundation, or PRF. Under the Purdue License Agreement, PRF granted Morphimmune a royalty-bearing,

transferable, worldwide, exclusive license, sublicensable through multiple tiers, under certain patents and technology owned by PRF relating

to, among other subject matter, drugs to target Fibroblast Activation Protein (FAP), to research, develop, manufacture, and commercialize

products covered by the licensed patents in all fields of use with limited exceptions. The license is subject to certain rights of the

U.S. government and rights retained by PRF (i) to practice and to license any government agencies, universities or other educational

institutions to practice, make, and use the intellectual property licensed to Morphimmune on a royalty-free basis for non-commercial uses,

(ii) to conduct activities required under sponsored research agreements with Morphimmune, and (iii) to disseminate and publish

materials and scientific findings from PRF’s research related to the intellectual property licensed to Morphimmune. Morphimmune

is obligated to use commercially reasonable efforts to develop and commercialize the licensed products in accordance with a development

and commercialization plan and to achieve agreed development milestones according to a specified timeline. PRF is obligated to prosecute

and maintain the licensed patents at Morphimmune’s cost and expense.

Under the Purdue License Agreement, Morphimmune paid PRF a one-time

upfront payment of $200,000 upon execution and $100,000 on each of the first and second anniversary of the effective date of the Purdue

License Agreement. During the period commencing on the date of first commercial sale of a licensed product and ending upon the date of

expiration of the last valid claim of the licensed patents covering such licensed product in a country, referred to as the royalty term,

Morphimmune will pay PRF an earned unit royalty of a low single-digit percentage on gross receipts from sale of the licensed product,

and beginning with the first sale of a licensed product, a tiered minimum annual royalty from the low to mid six-digit figure range less

the unit royalties due for the annual period. Upon the achievement of specified development and commercialization milestones, Morphimmune

will pay PRF the milestone payments as specified in the Purdue License Agreement, which may be up to $3.75 million in the aggregate. Morphimmune

is also required to pay PRF an annual maintenance fee ranging from a low five-digit figure to a low six-digit figure prior to first sale

of a licensed product and a low double-digit percentage of sublicense income received for sublicenses of licensed intellectual property,

with such percentage depending upon the timing of execution of the sublicense.

The Purdue License Agreement expires on a licensed product-by-licensed

product and country-by-country basis, upon expiration of the royalty term for such licensed product for the applicable country. Morphimmune

may terminate the Purdue License Agreement upon at least one month’s prior written notice to PRF. PRF may terminate the Purdue License

Agreement and the licenses granted thereunder if Morphimmune fails to cure a payment default or other material breach of the Purdue License

Agreement after written notice from PRF, or if Morphimmune becomes insolvent.

Manufacturing

We produce our lead antibodies at the laboratory scale necessary for

early research and development activities and some preclinical assessments. For later stage preclinical assessment, such as IND-enabling

studies and safety assessment and early-stage clinical assessment, we use third-party manufacturers to produce our antibodies, antibody

drug conjugates and drug substance for our FAP program, and any other necessary intermediates or reagents. We do not have, and we

do not currently plan to acquire or develop the infrastructure, facilities or capabilities to conduct these manufacturing activities ourselves.

We intend to continue to utilize third-party manufacturers to produce, package, label, test and release product for clinical and non-clinical

testing and for future commercial use, as needed. We expect to continue to rely on such third parties to manufacture our products for

the foreseeable future. Our expected future contractual manufacturing organizations will each have successful track records of producing

products for other companies under applicable compliance regulations, such as cGMP compliance in case of the FDA.

Competition

The development and commercialization of new product candidates is

highly competitive. We compete in the segments of the pharmaceutical, biotechnology and other related markets that develop therapies for

the treatment of cancer, which is highly competitive with rapidly changing standards of care. As such, our commercial opportunity could

be reduced or eliminated if our competitors develop and commercialize products that are safer, more effective, have fewer or less severe

side effects, are more convenient, or are less expensive than any products that we may develop or that would render any products that

we may develop obsolete or non-competitive. Our competitors also may obtain marketing approval for their products more rapidly than we

may obtain approval for ours, which could result in our competitors establishing a strong market position before we are able to enter

the market.

In oncology, we expect to compete with companies advancing antibodies,

antibody drug conjugates, or ADCs, small molecules, targeted radiotherapies, and other therapeutic modalities. We are aware of competitors

who are pursuing antibody-based discovery approaches, including, but not limited to, AbCellera Biologics, Inc.; Adaptive Biotechnologies

Corporation, or Adaptive; AIMM Therapeutics B.V.; IGM Biosciences, Inc.; OncoReponse, Inc. We also expect to compete with companies

pursuing targeted radiotherapies, including, but not limited to, RayzeBio, Fusion Pharmaceuticals, POINT Biopharma, Aktis Oncology, Actinium

Pharmaceuticals, and Yantai LNC Biotechnology. In addition, we expect to compete with large, multinational pharmaceutical companies that

discover, develop and commercialize antibodies, ADCs, small molecules, targeted radiotherapies, and other therapeutics for use in treating

cancer such as Immunogen (acquired by AbbVie Inc.), AstraZeneca; Amgen; Bayer AG, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; Eli Lilly and Company;

Genentech, Inc. (a member of Roche group); Merck & Co. Inc.; Novartis; Seagen (acquired by Pfizer) and Johnson &

Johnson. If any future product candidates identified through our current lead programs are eventually approved for sale, they will likely

compete with a range of treatments that are either in development or currently marketed for use in those same disease indications.

Subject to the closing of the Ayala Transaction and our acquisition

of AL102, we expect to compete with companies advancing treatment of desmoid tumors, including but not limited to, SpringWorks Therapeutics, Inc.

In November 2023, Springworks received FDA approval for its oral gamma secretase inhibitor, OGSIVEOTM (nirogacestat), for the treatment

of adult patients with progressing tumors who require systemic treatment. Desmoid tumors treatments also include surgery, hormonal therapy,

targeted therapy and chemotherapy.

There are several other companies developing FAP-targeted radioligand

therapies which may represent the most direct competition to our 177Lu-FAP program. Novartis is advancing a FAP-targeted radioligand therapy

(177Lu-FAP-2286) that was acquired from Clovis Oncology and is currently in Phase 1/2. Clovis previously presented Phase 1 data for FAP-2286

(June 2022.) In December 2023, Eli Lilly and Company acquired POINT Biopharma, which is developing a FAP-targeted radioligand

therapy (PNT2004) that is currently in Phase 1. POINT presented a trial-in-progress poster discussing trial design (June 2023) and

expects to release data from that trial in the first half of 2024. In addition, POINT has disclosed two preclinical radioligand programs

targeting FAP. Yantai LNC Biotechnology has also initiated a Phase 1 trial for another FAP-targeted radioligand therapy (LNC1004.) Additionally,

our 177Lu-FAP program faces competition from competitors who may have superior access to a consistent supply of radioactive isotopes.

In January 2023, we exclusively licensed a preclinical ROR1

ADC program from Zentalis with the potential to address hematologic and solid tumor indications. There are several other companies

developing antibodies, antibody-drug conjugates, and CAR-T therapies targeting ROR1, and they may represent the most direct

competition to our ROR1 ADC program. Merck has an ADC program (Zilovertamab vedotin) in a Phase 2/3 clinical trial for B-cell

lymphoma. Boehinger Ingelheim has an ADC program in a Phase 1/2 clinical trial (NBE-002) in solid tumors, and Legochem Biosciences

has an ADC program (LCB71) in a Phase 1 trial in solid tumors. Companies advancing clinical ROR1-CAR T therapy programs include

Octernal Therapeutics (ONCT-808) in a Phase 1/2 in B-cell malignancies, and Lyell Immunopharma (LYL797) in a Phase 1 trial.

Many of our competitors have significantly greater financial resources

and expertise in research and development, manufacturing, preclinical studies, conducting clinical studies, obtaining regulatory approvals

and marketing approved products than we have. These competitors also compete with us in recruiting and retaining qualified scientific

and management personnel and establishing clinical study sites and patient registration for clinical studies, as well as in acquiring

technologies complementary to, or necessary for, our programs. In addition, these larger companies may be able to use their greater market

power to obtain more favorable supply, manufacturing, distribution and sales-related agreements with third parties, which could give them

a competitive advantage over us.

Further, as more product candidates within a particular class of drugs

proceed through clinical development to regulatory review and approval, the amount and type of clinical data that may be required by regulatory

authorities may increase or change. Consequently, the results of our clinical trials for product candidates in that class will likely

need to show a risk benefit profile that is competitive with or more favorable than those products and product candidates in order to

obtain marketing approval or, if approved, a product label that is favorable for commercialization. If the risk benefit profile is not

competitive with those products or product candidates, or if the approval of other agents for an indication or patient population significantly

alters the standard of care with which we tested our product candidates, we may have developed a product that is not commercially viable,

that we are not able to sell profitably or that is unable to achieve favorable pricing or reimbursement. In such circumstances, our future

product revenue and financial condition would be materially and adversely affected.

Mergers and acquisitions in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries

may result in even more resources being concentrated among a smaller number of our competitors. Smaller and other early stage companies

may also prove to be significant competitors, particularly through collaborative arrangements with large and established companies. These

third parties compete with us in recruiting and retaining qualified scientific and management personnel, establishing clinical study sites

and subject enrollment for clinical studies, as well as in acquiring technologies complementary to, or necessary for, our current or future

products or programs.

Intellectual Property

Intellectual property is of vital importance in our field and in biotechnology

generally. We seek to protect and enhance proprietary technology, inventions, and improvements that are commercially important to the

development of our business by seeking, maintaining, and defending patent rights, whether developed internally, acquired or licensed from

third parties. We will also seek to rely on regulatory protection afforded through orphan drug designations, inclusion in expedited development

and review, data exclusivity, market exclusivity and patent term extensions where available.

We utilize various types of intellectual property assets to provide

multiple layers of protection. For example, we seek a variety of patents to protect our inventions including, for example, compositions

of matter and uses in treatment and diagnostic and methods for novel antibodies, including methods of treatment for diseases expressing

novel targets. We believe our current layered patent estate, together with our efforts to develop and patent next generation technologies,

provides us with substantial intellectual property protection.

As of February 8, 2024, we own or exclusively in-license 1 issued

U.S. patent, 6 pending U.S. non-provisional patent applications, 1 pending U.S. provisional patent application, and 53 pending patent

applications in Australia (3), Brazil (3), Canada (4), China (4), Europe (5), Hong Kong (1), Israel (3), India (3), Japan (4),

Korea (3), Mexico (3), New Zealand (3), Russia (3), Singapore (3), Taiwan (3), South Africa (3), and the UAE (2) , in total 6 patent

families, covering our IM-4320 (IL-38), IM-1021 (ROR1), and IM-3050 (177Lu-FAP) products. Our portfolio includes issued

and/or pending claims directed to the composition of matter and methods of use for IM-4320, IM-1021 and IM-3050. Patent applications

covering IM-4320, if issued, are expected to expire between 2040 and 2042, absent any patent term extensions or adjustments and without

accounting for terminal disclaimers. Patent applications covering IM-1021, if issued, are expected to expire in 2042, absent any patent

term extensions or adjustments and without accounting for terminal disclaimers. Patent applications covering IM-3050, if issued, are expected

to expire in 2045, absent any patent term extensions or adjustments and without accounting for terminal disclaimers. However, we recognize

that the area of patent and other intellectual property rights in biotechnology is an evolving one with many risks and uncertainties,

which may affect those rights.

Our commercial success will depend in significant part upon obtaining

and maintaining patent protection and trade secret protection for our targeted effector-based therapeutics and the methods used to develop

and manufacture them, as well as successfully defending these patents against third-party challenges and operating without infringing

on the proprietary rights of others. Our ability to stop third parties from making, using, selling, offering to sell or importing our

products depends on the extent to which we have rights under valid and enforceable patents or trade secrets that cover these activities.

We cannot be sure that patents will be granted with respect to any of our pending patent applications or with respect to any patent applications

filed by us in the future, nor can we be sure that any of our existing patents, or any patents granted to us in the future will be commercially

useful in protecting our targeted effector-based therapeutics, current programs and processes. For this and more comprehensive risks related

to our intellectual property, please see the section titled “Risk Factors — Risks Related to Our Intellectual

Property.”

The term of individual patents depends upon the legal term of the patents

in the countries in which they are obtained. In most countries in which we file, including the United States, the patent term is 20 years

from the earliest date of filing a non-provisional patent application. In the United States, a patent’s term may potentially be

lengthened by patent term adjustment, or PTA, which compensates a patentee for administrative delays by the USPTO in examining and granting

a patent. In the United States, the patent term of a patent that covers an FDA-approved drug may also be eligible for patent term extension, or PTE,

which permits patent term restoration as compensation for the patent term lost during the FDA regulatory review process. The Hatch-Waxman

Act permits PTE of up to five years beyond the expiration of the patent. The length of the PTE accorded a patent is related to the

length of time the drug is under regulatory review by the FDA. PTE cannot extend the remaining term of a patent beyond a total of 14 years

from the date of product approval. Further, only one patent applicable to an approved drug may be extended, and only those claims covering

the approved drug, a method for using it, or a method for manufacturing it may be extended. Similar provisions for extending the term

of a patent that covers an approved drug are available in multiple European countries and other foreign jurisdictions. In the future,

if and when our products receive FDA approval, we expect to apply for patent term extensions on patents covering those products. We expect

to seek patent term extensions to all of our issued patents in any jurisdiction where these are available; however, there is no guarantee

that the applicable authorities, including the FDA in the United States, will agree with our assessment of whether such extensions should

be granted, and if granted, the length of such extensions. Patent term in the U.S. may be shortened if a patent is terminally disclaimed

over an earlier-filed patent.

In some instances, we file provisional patent applications directly

in the USPTO. Provisional patent applications are designed to provide a lower-cost first patent filing in the United States. Corresponding

non-provisional patent applications must be filed not later than 12 months after the provisional application filing date. The corresponding

non-provisional application benefits in that the priority date(s) of the non-provisional patent application is/are the earlier provisional

application filing date(s), and the patent term of the finally issued patent is calculated from the earliest non-provisional application

filing date. This system allows us to obtain an early priority date, obtain a later start to the patent term and to delay prosecution

costs, which may be useful in the event that we decide not to pursue examination in a subsequent non-provisional application. While we

intend, as appropriate, to timely file non-provisional patent applications relating to our provisional patent applications, we cannot

predict whether any such non-provisional patent applications will result in the issuance of patents that provide us with any competitive

advantage.

We intend to file U.S. non-provisional applications and/or international

Patent Cooperation Treaty, or PCT, applications that claim the benefit of the priority date of earlier filed provisional or non-provisional

applications, when applicable. The PCT system allows for a single PCT application to be filed within 12 months of the priority filing

date of a corresponding priority patent application, such as a U.S. provisional or non-provisional application, and to designate all of

the 157 PCT contracting states in which national phase patent applications can later be pursued based on the PCT application. The PCT

International Searching Authority performs a patentability search and issues a non-binding patentability opinion which can be used to

evaluate the chances of success for the national applications in foreign countries prior to having to incur the filing fees. Although

a PCT application does not issue as a patent, it allows the applicant to establish a patent application filing date in any of the member

states and then seek patents through later-filed national-phase applications. No later than either 30 or 31 months from the earliest

priority date of the PCT application, separate national phase patent applications can be pursued in any of the PCT member states, depending

on the deadline set by individual contracting states. National phase entry can generally be accomplished through direct national filing

or, in some cases, through a regional patent organization, such as the European Patent Organization. The PCT system delays application

filing expenses, allows a limited evaluation of the chances of success for national/regional patent applications and allows for substantial

savings in comparison to having filed individual countries rather than a PCT application in the event that no national phase applications

are filed.

For all patent applications, we determine claiming strategy on a case-by-case

basis. Advice of counsel and our business model and needs are always considered. We file patent applications containing claims for protection

of all commercially-relevant uses of our proprietary technologies and any products, as well as all new applications and/or uses we discover

for existing technologies and products, assuming these are strategically valuable. We may periodically reassess the number and type of

patent applications, as well as the pending and issued patent claims to ensure that coverage and value are obtained for our processes,

and compositions, given existing patent law and court decisions. Further, claims may be modified during patent prosecution to meet our

intellectual property and business needs.

We recognize that the ability to obtain patent protection and the degree

of such protection depends on a number of factors, including the extent of the prior art, the novelty and non-obviousness of the invention,

and the ability to satisfy subject matter, written description, and enablement requirements of the various patent jurisdictions. In addition,

the coverage claimed in a patent application can be significantly reduced before the patent is issued, and its scope can be reinterpreted

or further altered even after patent issuance. Consequently, we may not obtain or maintain adequate patent protection for any of our targeted

effector-based therapeutics. We cannot predict whether the patent applications we are currently pursuing will issue as patents in any

particular jurisdiction or whether the claims of any issued patents will provide sufficient proprietary protection from competitors. Any

patents that we hold may be challenged, circumvented or invalidated by third parties.

In addition to patent protection, we also rely on trademark registration,

trade secrets, know how, other proprietary information and/or continuing technological innovation to develop and maintain our competitive

position. We seek to protect and maintain the confidentiality of proprietary information to protect aspects of our business that are not

amenable to, or that we do not consider appropriate for, patent protection. Although we take steps to protect our proprietary information

and trade secrets, including through contractual means with our employees and consultants, third parties may independently develop substantially

equivalent proprietary information and techniques or otherwise gain access to our trade secrets or disclose our technology. Thus, we may

not be able to meaningfully protect our trade secrets. It is our policy to require our employees, consultants, outside scientific collaborators,

sponsored researchers and other advisors to execute confidentiality agreements upon the commencement of employment or consulting relationships

with us. These agreements provide that all confidential information concerning our business or financial affairs developed or made known

to the individual during the course of the individual’s relationship with us is to be kept confidential and not disclosed to third

parties except in specific circumstances. Our agreements with employees also provide that all inventions conceived by the employee in

the course of employment with us or from the employee’s use of our confidential information are our exclusive property. However,

such confidentiality agreements and invention assignment agreements can be breached, and we may not have adequate remedies for any such

breach. In addition, our trade secrets may otherwise become known or be independently discovered by competitors. To the extent that our

consultants, contractors or collaborators use intellectual property owned by others in their work for us, disputes may arise as to the

rights in related or resulting trade secrets, know-how and inventions.

The patent positions of biotechnology companies like ours are generally

uncertain and involve complex legal, scientific and factual questions. Our commercial success will also depend in part on not infringing

upon the proprietary rights of third parties. It is uncertain whether the issuance of any third-party patent would require us to alter

our development or commercial strategies, or our products or processes, obtain licenses or cease certain activities. Our breach of any

license agreements or our failure to obtain a license to proprietary rights required to develop or commercialize our future products may

have a material adverse impact on us. If third parties prepare and file patent applications in the United States that also claim technology

to which we have rights, we may have to participate in interference or derivation proceedings in the USPTO to determine priority of invention.

When available to expand market exclusivity, our strategy is to obtain,

or license additional intellectual property related to current or contemplated development platforms, core elements of technology and/or

programs and targeted effector-based therapeutics.

For more information regarding the risks related to our intellectual

property, see the section titled “Risk Factors — Risks Related to Our Intellectual Property.”

Government Regulation

The FDA and other regulatory authorities at federal, state, and local

levels, as well as in foreign countries, extensively regulate, among other things, the research, development, testing, manufacture, quality

control, import, export, safety, effectiveness, labeling, packaging, storage, distribution, record keeping, approval, advertising, promotion,

marketing, post-approval monitoring, and post-approval reporting of drugs and biologics. We, along with our third-party contractors, will

be required to navigate the various preclinical, clinical and commercial approval requirements of the governing regulatory agencies of

the countries in which we wish to conduct studies or seek approval or licensure of our programs and development candidates.

U.S. Government Regulation of Drugs and Biologics

In the United States, the FDA regulates drugs under the Federal Food,

Drug, and Cosmetic Act, or FDCA, and its implementing regulations and biologics under the FDCA, the Public Health Service Act, or PHSA,

and their implementing regulations. Both drugs and biologics also are subject to other federal, state and local statutes and regulations.

The process of obtaining regulatory approvals and the subsequent compliance with appropriate federal, state and local statutes and regulations

requires the expenditure of substantial time and financial resources. Failure to comply with the applicable U.S. requirements may subject

an applicant to administrative or judicial sanctions, such as FDA refusal to approve pending new drug applications, or NDAs, or biologics

license applications, or BLAs, or the agency's issuance of warning letters, or the imposition of fines, civil penalties, product recalls,

product seizures, total or partial suspension of production or distribution, injunctions and/or criminal prosecution brought by the FDA

and the U.S. Department of Justice or other governmental entities.

Nonclinical and Clinical Development

Nonclinical studies include laboratory evaluation of product chemistry

and formulation and may involve in vitro testing or in vivo animal studies to assess the potential for toxicity,

adverse events, and other safety characteristics of the program or development candidate, and in some cases to establish a rationale for

therapeutic use. The conduct of nonclinical studies is subject to federal regulations and requirements, including good laboratory practice regulations for

safety/toxicology studies.