What's Driving Everything From a Market Frenzy to an Embrace of U.S. Deficits? Magical Thinking.

January 30 2021 - 11:04AM

Dow Jones News

By Greg Ip

The Wall Street bulls embracing sky-high stock values and the

Washington pols embracing big deficits may be ideological

opposites, but they have something important in common. Both draw

sustenance from near-zero interest rates which make stocks more

valuable and debt more supportable. And both risk taking this

basically sound logic to extremes.

The rally in everything from big tech stocks to Tesla Inc. to

bitcoin are all manifestations of what Wall Street calls "TINA" for

"there is no alternative": when bank deposits pay nothing and

government bonds next to nothing, investors will grasp at almost

anything in search of a return.

Directionally, this is not wrong. The value of an asset is its

future income, discounted to the present using interest rates, plus

a "risk premium" -- the extra return you expect for owning

something riskier than a government bond. A declining interest rate

or risk premium boosts the present value of that future income.

This can certainly justify some of the market's rally. The ratio

of the S&P 500 to expected earnings has jumped from 18 in 2019

to 22 now, lowering the inverse of that ratio, the "earnings

yield," from about 5.5% to 4.6%. That happens to closely track the

decline in the 10-year Treasury yield from 1.9% to around 1%. Low

rates also help explain the outperformance of big growth companies

like Apple Inc. and Amazon.com Inc., for whom the bulk of profits

lie far in the future.

Has this gone too far? In a blog post Aswath Damodaran, a New

York University finance professor, worked out the intrinsic value

of the S&P 500 assuming bond yields at 2% over the long run and

an equity risk premium of 5%. The result: The S&P on Friday was

roughly 11% overvalued.

Maybe that's not bubble territory, but it's definitely

expensive. And while you can justify the overall market level with

moderately bullish assumptions, you need ever more contrived

arguments as the spotlight moves to individual sectors and

stocks.

To justify Apple's current value, you need a lot of confidence

about how the next few years will turn out. To justify Tesla's, you

need a lot of confidence about the next few decades. To justify

GameStop's -- well, has anyone who bought it recently thought

beyond the next few days?

The same low-rate logic fueling the everything rally has now

found its way into the fiscal debate in Washington. Congress in the

last year has borrowed roughly $3.4 trillion to combat the pandemic

and its economic fallout, and President Biden has proposed

borrowing $1.9 trillion more. These sums would together equal

roughly 25% of gross domestic product -- the largest burst of

national borrowing since World War II.

In advocating for this package, Mr. Biden and Treasury Secretary

Janet Yellen note that interest rates are historically low. Despite

this added debt, interest expense won't be much higher as a share

of GDP than a few years ago. The Federal Reserve says it will keep

short-term rates near zero for several years to get unemployment

down and inflation up. If it succeeds, that's great news for stock

bulls and debt doves.

In her confirmation hearing, Ms. Yellen cautioned that the U.S.

debt trajectory is a "cause for concern." Budget deficits must be

brought down to levels that stabilize the debt in the "longer

term," she said, meaning that's a problem to address another

day.

As with the stock market, the problem here isn't with Ms.

Yellen's fairly conventional take on interest rates and debt, but

with others who go even further. They argue there is no limit to

how much the U.S. can borrow: It can always repay the debt by

printing more dollars, and dispute that more debt must lead to

higher rates, noting rates have fallen as debts have risen in the

last decade. Thus, they argue, Mr. Biden must not let alarmist

rhetoric about the debt hold back funding for his priorities on

inequality, climate, and health care, nor worry if some spending

isn't particularly effective such as $1,400 checks to affluent

families who will simply save it.

Yet this logic assumes interest rates are somehow independent of

the level of debt. In fact, there is some level of borrowing that

would eventually push up inflation and interest rates. No one knows

what that level is, though it has clearly risen because private

borrowing has been depressed. But if the U.S. proceeds as if no

limit exists, it is more likely to hit it. "Inflation might be a

greater danger precisely because it's no longer perceived as such,"

former Federal Reserve official Bill Dudley wrote last year.

Finally, how much debt the U.S. can carry depends not just on

interest rates but on GDP. Indeed rates were low even before the

pandemic because GDP growth had been trending down, perhaps due to

aging populations world-wide. To be sure, well targeted stimulus

now should speed up recovery, helping the economy's debt-carrying

capacity. On the other hand, the U.S. has also experienced two

economic disasters within 12 years of each other, which pushed down

the path of GDP and pushed up debt. However much fiscal space the

U.S. has, responding to those disasters has consumed quite a bit of

it: Federal debt has risen from 35% to over 100% of GDP since

2007.

It might want to keep some fiscal space in reserve in case of

another disaster.

Write to Greg Ip at greg.ip@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

January 30, 2021 10:49 ET (15:49 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2021 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

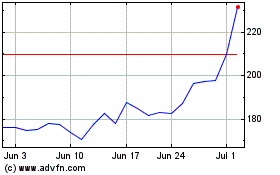

Tesla (NASDAQ:TSLA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Dec 2024 to Jan 2025

Tesla (NASDAQ:TSLA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jan 2024 to Jan 2025