By Jeff Horwitz and Keach Hagey

Google for years operated a secret program that used data from

past bids in the company's digital advertising exchange to

allegedly give its own ad-buying system an advantage over

competitors, according to court documents filed in a Texas

antitrust lawsuit.

The program, known as "Project Bernanke," wasn't disclosed to

publishers who sold ads through Google's ad-buying systems. It

generated hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue for the

company annually, the documents show. In its lawsuit, Texas alleges

that the project gave Google, a unit of Alphabet Inc., an unfair

competitive advantage over rivals.

The documents filed this week were part of Google's initial

response to the Texas-led antitrust lawsuit, which was filed in

December and accused the search giant of running a digital-ad

monopoly that harmed both ad-industry competitors and publishers.

This week's filing, viewed by The Wall Street Journal, wasn't

properly redacted when uploaded to the court's public docket. A

federal judge let Google refile it under seal.

Some of the unredacted contents of the document were previously

disclosed by MLex, an antitrust-focused news outlet.

The document sheds further light on the state's case against

Google, along with the search giant's defense.

Much of the lawsuit involves the interplay of Google's roles as

both the operator of a major ad exchange -- which Google likens to

the New York Stock Exchange in marketing documents -- and a

representative of buyers and sellers on the exchange. Google also

acts as an ad buyer in its own right, selling ads in its own

properties like search and YouTube via these same systems.

Texas alleges that Google used its access to data from

publishers' ad servers -- where more than 90% of large publishers

use Google to sell their digital ad space -- to guide advertisers

toward the price they would have to bid to secure an ad

placement.

Google's use of bidding information, Texas alleges, amounted to

insider trading in digital ad markets. Because Google had exclusive

information about what other ad buyers were willing to pay, the

state says, it could unfairly compete against rival ad-buying tools

and pay publishers less on its winning bids for ad inventory.

The unredacted documents show that Texas claims Project Bernanke

is a critical part of that effort.

Google acknowledged the existence of Project Bernanke in its

response and said in the filing that "the details of Project

Bernanke's operations are not disclosed to publishers."

Google denied in the documents that there was anything

inappropriate about using the exclusive information it possessed to

inform bids, calling it "comparable to data maintained by other

buying tools."

Peter Schottenfels, a Google spokesman, said the complaint

"misrepresents many aspects of our ad tech business. We look

forward to making our case in court." He also referred the Journal

to an analysis conducted by a U.K. advertising group that concluded

Google didn't appear to have had an advantage.

The Texas attorney general's office didn't immediately respond

to requests for comment.

Google's outsize role in the digital-ad market is both

controversial and at times murky.

In some instances, "we're on both the buy side and the sell

side," Google chief economist Hal Varian said at a 2019 antitrust

conference held by the University of Chicago's Booth School of

Business. Asked how the company managed those roles, Mr. Varian

said the topic was "too detailed for the audience, and me."

In the filing, Google said Project Bernanke used data about

historical bids made through Google Ads to adjust its clients' bids

and increase their chances of winning auctions for ad impressions

that would have otherwise been won by rival ad tools. The company

also acknowledged as accurate an internal 2013 presentation showing

that the project was expected to generate $230 million in revenue

that year; Texas has cited that presentation as proof that Google

benefited from its advantage.

The document also sheds more light on a once-secret deal between

Facebook Inc. and Google, dubbed Jedi Blue, that allegedly

guaranteed Facebook would both bid in -- and win -- a fixed

percentage of ad auctions.

"The agreement was signed by, among other individuals, Philipp

Schindler, Google's Senior Vice President and Chief Business

Officer, and Sheryl Sandberg, Facebook's Chief Operating Officer,"

an unredacted section of Google's filing states.

Google acknowledged in its responses that it had agreed to make

"commercially reasonable efforts" to ensure Facebook was able to

identify 80% of mobile users and 60% of desktop users, excluding

users of Apple's Safari web browser, in ad auctions. The Texas

complaint alleges that this activity appears "to allow Facebook to

bid and win more often in auctions."

Google further acknowledged in the filing that Jedi Blue

required Facebook to spend $500 million or more in Google's Ad

Manager or AdMob auctions in the fourth year of the agreement, and

that Facebook committed to making commercially reasonable efforts

to win 10% of the auctions in which it had bids.

Facebook didn't immediately comment on the new information in

the documents. The company has said it doesn't believe it was given

special treatment compared to other Google partners.

Write to Jeff Horwitz at Jeff.Horwitz@wsj.com and Keach Hagey at

keach.hagey@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 10, 2021 19:51 ET (23:51 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2021 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

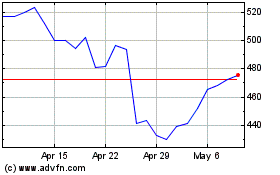

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jan 2025 to Feb 2025

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Feb 2024 to Feb 2025