By Saabira Chaudhuri

MUSSOORIE, India -- A generation of Indians has grown up on

instant noodles brand Maggi, which accounts for one in every four

dollars Nestlé SA makes in India. But its nonrecyclable packaging

has become a big problem -- for both India and Nestlé.

Yellow Maggi packets and other plastic waste increasingly blight

this verdant town in the foothills of the Himalayas and are strewn

across India. Now, Maggi packets -- along with chip bags, candy

wrappers and shampoo pouches from the world's biggest brands -- are

the target of new laws in India, forcing consumer-goods companies

to grapple with the waste their products generate.

The daily plastic waste generated by the average Indian -- while

much lower than the average American -- climbed 69% between 2015

and 2018, according to government estimates. Across the country,

dumps are overflowing and drains are clogging with plastic, while

cows -- considered sacred -- are getting sick after eating

packaging.

To get a grip, India has instituted some of the world's

strictest rules on single-use plastic, forcing companies to collect

packaging that is often left as litter. The country's environment

minister even launched a Bollywood-style song -- complete with

dance moves -- to persuade Indians to reject single-use

plastics.

India's stance is part of a broader crackdown by regulators the

world over on plastic that is used just once but can inflict

lasting damage on marine life and the environment.

Consumer goods companies for decades have focused on marketing

and sales, pumping out billions of nonrecyclable packets of

everything from shampoo to coffee, with little regard for their

disposal. Now the threat of fines or an outright ban on packaging

that has been crucial to their success here is a major concern.

Companies are counting on growth in India -- on track to overtake

China as the world's most populous nation by 2022 -- to help offset

slowing sales in the West.

"The narrative on plastic has changed dramatically," Sanjiv

Mehta, head of Unilever PLC's South Asia business, told investors

in December. India is Unilever's second-biggest market, with

plastic pouches of its Sunsilk shampoo and Bru instant coffee

hanging from tiny shop fronts across the country.

Nonrecyclable packaging is a problem globally, but particularly

acute in countries with poor waste management. Many Indian

households lack regular collection services so they burn trash or

dump it on the side of the road. Much of the waste ends up in

waterways. Of plastic found in the world's oceans, 90% is traced to

10 rivers, according to a 2017 study published in the journal

Environmental Science & Technology. Eight of the rivers are in

Asia and two flow through India.

In emerging markets, products like shampoo and detergent are

often sold in single-serve pouches similar to the ketchup packets

that come with an order of fries. The resilient "multilayer"

pouches protect against extreme temperatures and contamination,

and, most important, are affordable for poor consumers.

Single-serve packets make up over 80% of shampoo sales in India,

Indonesia and the Philippines, according to Euromonitor.

But like Maggi, this type of packaging combines different types

of plastic with materials like aluminum. That makes it

nonrecyclable and of no interest to India's waste pickers who trawl

through trash looking for recyclables to sell.

Three years ago, India's government said it would ban multilayer

packaging by 2018, setting off alarm bells through the

industry.

"We didn't want the government to phase this out and put the

whole consumer-goods industry into jeopardy," says Samir Pathak,

PepsiCo's sustainability chief for Asia, the Middle East and North

Africa.

A consortium -- including Nestlé, Pepsi and Mentos-maker

Perfetti Van Melle SpA -- tried for months to develop a recyclable

alternative. After little success, they decided on a different

approach.

Through street plays and workshops, the companies trained 1,500

waste pickers across eight cities to identify and collect

multilayer packaging, paying them for what they brought in.

The pilot program amassed 680 metric tons of material in three

months. In March 2018, New Delhi changed the law to allow the sale

of multilayer packaging. The caveat is that companies must collect

back the equivalent volume of what they sell and find other uses

for it, like sending it to cement plants as fuel.

That is prompting Nestlé and others to hire businesses,

nongovernmental organizations and local governments to collect back

packaging. Companies must collect 100% of their multilayer

packaging by the end of next year. Half the battle is getting

households to sort the garbage rather than throwing it all in one

bin.

In Mussoorie, Nestlé is sending people door to door to educate

residents about proper disposal and funding plastic-packaging

cleanups, moves it hopes to replicate elsewhere.

On a recent morning, 21-year-old Kiran accompanied Poonam, a

waste picker, on her rounds in the town. Both women go by just

their first names as is common in much of India. Kiran, whose work

is funded by Nestlé, asked homemakers who answered her knock to

separate packaging from "wet" waste. Only then can it be recycled,

composted or used as fuel.

"You should have at least two bins, one for wet and one for dry

waste," Kiran told a woman who was handing over a bag of mixed

trash.

She unfurled a cement bag repurposed to serve as an educational

poster, with a Maggi packet, snack bag and plastic bottle stapled

to one end and crayon drawings of fruits and vegetables on the

other to illustrate different kinds of waste.

In Bangalore, Unilever has started paying a waste-management

firm, Saahas, to collect multilayer plastic from offices and

apartment buildings.

In a sprawling office complex where 60,000 people work for

companies like Morgan Stanley and Capgemini, Saahas staff trawl

through bags of dry waste each morning. After pulling out bulky

items like bottles, cans and big pieces of cardboard, the waste is

sent to a factory on the city outskirts where conveyor-belt workers

pick out multilayer packaging by hand. It is then trucked to a

cement kiln 600 kilometers away for fuel.

Trucking plastic long distances to be burned hurts the

environment, says Madhavi Purohit, Unilever's senior

packaging-sustainability manager for Asia. But she adds that it is

still better than adding to landfills.

Unilever declined to disclose how much the process costs but

says it pays for transportation and even pays the kilns to accept

its packaging.

Collecting from office and apartment buildings that already

separate waste is low-hanging fruit. The bigger challenge is how to

reduce litter and improve household waste separation.

Unilever has developed a four-week course for schools called

Plastic Safari to explain the merits of separating waste and

recycling. It is also lobbying education officials to include waste

segregation and recycling in the regular curriculum, hoping

children will influence their parents.

Despite such efforts, some government officials have accused

companies of moving too slowly. E. Ravendiran of the Maharashtra

Pollution Control Board says companies only swung into action after

being threatened with bans or having to pay a deposit on multilayer

packaging sold.

Executives say the target of collecting 100% of multilayer

plastic by 2020 is unrealistic and that details on how the rule

will be implemented are scarce.

Hassan, a former waste picker who manages a small team of waste

collectors in Bangalore, says pickers aren't financially motivated

to bend down hundreds of times to collect a kilogram of multilayer

plastic from piles of mixed waste or just off the street. Saahas

pays him 27 rupees (around 39 U.S. cents) for one kilogram of

plastic bottles, compared with just 4 rupees for one kilogram of

multilayer packaging, which is much harder to collect.

As volumes ramp up and costs rise, companies are looking to

monetize what they collect. Some are researching other uses for

discarded packaging, like in roads or furniture, or are trying to

make packaging with just one type of plastic so it can be recycled.

Unilever has opened a plant in Indonesia to test recycling pouches

that borrows technology used to recycle plastic components for

electronic devices. Nestlé on Tuesday launched a recyclable paper

wrapper for one of its snack bars in Europe, which previously came

in a plastic wrapper.

Fixing Mussoorie's trash problem won't be easy. Collecting waste

from houses cut into the steep hillside is punishing work.

Torrential rain means plastic litter gets buried and is tough to

extract. Bands of monkeys overturn bins and tear open flimsy bags

of waste. During the summer, Mussoorie's cool temperatures are a

magnet for tourists, doubling waste and straining the resources of

a town that doesn't have a regulated landfill or incineration

facility.

Nestlé's education effort -- which began in January -- spans

1,800 homes. It plans to eventually reach all 13,000 in the town,

along with hundreds of hotels and businesses. It has also run radio

and newspaper campaigns to discourage littering and encourage the

separation of waste.

"We are looking at this project as a model for a city," says

Tulika Shukla, Nestlé's manager for packaging sustainability in

India.

Critics say the Mussoorie program is a drop in the bucket and

that in most Indian cities a door-to-door campaign isn't

viable.

Nestlé estimates it collected the equivalent of more than 20% of

the multilayer plastic packaging it sold across India last year. To

hit the government-mandated target of 100% by next year it has to

scale up significantly.

In Mussoorie, Nestlé's Maggi packets are the biggest source of

multilayer plastic waste, according to a study by the nonprofit

Gati Foundation. It says 1,000 Maggi packets are used each day

across 60 roadside stalls called "Maggi Points."

Gati and town officials have asked the company to ditch

single-serve packets in favor of bulk packaging. Nestlé says it

can't because of food-safety concerns once a packet is opened. In

May, the company said it would start running a yearlong

waste-collection service for the stalls.

"You feel like crying," said Sanjeev Chopra, who runs the

Mussoorie-based national training institute for civil servants.

"The Himalayas are polluted all over with Maggi packets."

Write to Saabira Chaudhuri at saabira.chaudhuri@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

July 05, 2019 07:14 ET (11:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

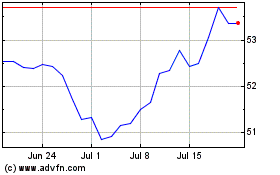

Unilever (EU:UNA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Nov 2024 to Dec 2024

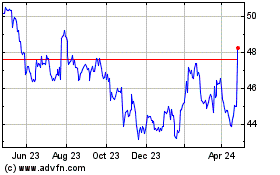

Unilever (EU:UNA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Dec 2023 to Dec 2024