Supreme Court weighs levies on third-party goods sold on Amazon

and other marketplaces

By Richard Rubin and Laura Stevens

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (April 16, 2018).

Billions of dollars of goods sold each year by independent

merchants on Amazon.com and other online marketplaces would be

vulnerable to state sales taxes for the first time if justices

decide to reverse a quarter-century-old precedent in a case before

the Supreme Court this week.

In the case, South Dakota is seeking to overturn a longtime

precedent under which states can't require retailers to collect

sales taxes unless the companies have a physical presence in the

state. While Amazon.com Inc. itself collects sales taxes on its own

products, it does not on most others' sales through its

platform.

Justices on Tuesday will hear arguments in the case, South

Dakota v. Wayfair Inc., and a decision is expected by the end of

June.

The current tax rules -- from the era of mail-order catalogs --

helped fuel the rise of internet commerce and spurred frustration

among brick-and-mortar retailers, shopping-mall owners and state

governments.

Tax and legal experts expect the court to overturn the

precedent, freeing states to collect levies on future cross-state

transactions. It isn't clear what new standard might take its place

or what rules states might impose.

President Donald Trump recently put the issue of sales-tax

collection in the spotlight as part of his repeated attacks on

Amazon, which people close to the White House attribute largely to

his dislike of coverage of his administration by the Washington

Post, owned separately by Amazon Chief Executive Jeff Bezos. Mr.

Trump said that Amazon avoids taxes and that its growing dominance

is "putting many thousands of retailers "out of business."

The biggest effects would be felt on online marketplaces, where

between $3.9 billion and $6.2 billion in taxes could have been

collected on goods sold by smaller vendors in 2017, according to

the Government Accountability Office. On such marketplaces, run by

Amazon, eBay Inc. and others, independent sellers give the

platforms a cut of their sales.

Merchants selling goods on Amazon's global marketplace last year

made up nearly two-thirds of gross merchandise volume, which

totaled $313.4 billion, according to Factset analyst estimates.

Half of all items sold come from those small or midsize businesses,

according to Amazon.

A few states, including Washington and Pennsylvania, have

already started trying to tax third-party online marketplace sales,

and those efforts could accelerate after a Supreme Court

decision.

"It could be read as a green light to 'Go for it, states,' and

they will go for it," said Richard Pomp, a law professor at the

University of Connecticut.

The 1992 opinion, in the case of Quill Corp. v. North Dakota,

held that the Constitution's commerce clause limited interstate tax

enforcement without congressional assent. Justice John Paul Stevens

said it was up to Congress to set nationwide rules for cross-border

sales-tax enforcement, but Congress hasn't done so.

State governments and brick-and-mortar shops argue the 1992

precedent harms state treasuries and disadvantages taxpaying

homegrown businesses. In a related case three years ago, Justice

Anthony Kennedy, who voted for the Quill ruling in 1992, filed a

concurring opinion suggesting the time had come to reconsider the

question. South Dakota quickly enacted a tax statute designed to

give the high court such an opportunity.

The state sued Wayfair, an online home-goods retailer, and other

larger internet-based sellers. The South Dakota Supreme Court sided

with Wayfair under the 1992 precedent, and the state then appealed.

Wayfair says it collects and remits taxes on about 80% of its

sales.

States, large retailers, shopping-center owners and the Trump

administration want the court to let states extend sales-tax

collections to online merchants based elsewhere. They argue that

technological advances made the physical-presence standard set out

in the 1992 precedent obsolete and that the ruling has left holes

on Main Streets and in government budgets.

South Dakota asks the court to extend state authority over

merchants with an "economic presence" in their territory, arguing

that it is a better reflection of business ties to a state than the

20th century "physical presence" standard. The South Dakota law

would extend the collection mandate to sellers doing at least

$100,000 of business or conducting more than 200 transactions with

state residents.

"It is clearly a competitive disadvantage if you are required to

collect sales tax and some competitor isn't," said Tom McGee,

president and CEO of the International Council of Shopping

Centers.

States say software can help online sellers comply with multiple

taxing jurisdictions and definitions and that small-business

exceptions could soften the compliance burden.

Conservatives and online retailers warn about expanded state

power and fear states would reach outside their borders to audit

sellers with no representation.

In the early days of e-commerce, Amazon prospered by lacking a

physical presence in many states. The company could ship goods from

a few places and most consumers wouldn't pay sales taxes, giving

Amazon a discount over in-state companies. States, retailers and

shopping mall owners pressed Congress for a federal standard for

taxing out-of-state sellers. Congress hasn't acted.

As states started getting more aggressive in defining physical

presence, Amazon built a network of distribution and fulfillment

centers that allow faster delivery. Now, the company collects taxes

on its own sales in all 45 states with sales taxes and has some

voluntary agreements for tax collection with municipalities. In

most cases, however, it doesn't collect taxes on sales by other

parties on its marketplace.

Amazon declined to comment. The company supports federal

legislation but hasn't weighed in on the court case.

"A world in which state tax power is unbounded by geography is

undoubtedly a world that is bad for Amazon," said Andrew Moylan,

executive vice president at the National Taxpayers Union

Foundation, which wants the court to preserve the physical-presence

standard.

Amazon typically collects a roughly 15% cut for items sold by

outside vendors on its site, plus warehousing and logistics fees.

In addition, it doesn't have to take inventory risk while

increasing its selection. In its most recent quarter, its

seller-services revenue grew 41% to $10.52 billion.

Other online retailers with a stake in the Supreme Court case

include eBay and the Trump Organization's own e-commerce operation,

TrumpStore.com, which doesn't collect taxes for the vast majority

of states. As of earlier this month, TrumpStore.com collected sales

tax for merchandise shipped to Louisiana and Florida, and the

website now indicates that it also collects sales taxes for

products shipped to Virginia.

--Jess Bravin contributed to this article.

Write to Richard Rubin at richard.rubin@wsj.com and Laura

Stevens at laura.stevens@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 16, 2018 02:47 ET (06:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

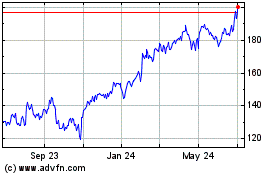

Amazon.com (NASDAQ:AMZN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Nov 2024 to Dec 2024

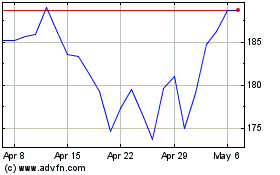

Amazon.com (NASDAQ:AMZN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Dec 2023 to Dec 2024