By Rachel Louise Ensign and Andrew Ackerman

Washington has claimed its second Wells Fargo & Co. chief

executive.

John Stumpf quit the bank 13 days after a brutal appearance

before Congress. His successor, Timothy Sloan, lasted 16 days

before stepping down.

When Mr. Stumpf went to Congress in 2016 after a sales scandal

erupted at Wells Fargo, he blamed low-level employees and gave

evasive responses. Eager to avoid his predecessor's missteps, Mr.

Sloan prepared for his most recent appearance before Congress by

sounding out lawmakers and showcasing the bank's efforts to regain

customer trust.

But it was too late. By the time Mr. Sloan took his seat before

the House Financial Services Committee earlier this month, Wells

Fargo was on the outs with Washington. Problems had emerged across

the bank's other businesses, setting off a flurry of government

investigations. The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and

the Federal Reserve, the bank's main regulators, were losing

patience.

The OCC was debating the rare step of forcing changes to Wells

Fargo's senior management or board, The Wall Street Journal has

reported. The Federal Reserve was showing no signs it was ready to

lift an unprecedented cap on the bank's growth put in place a year

earlier.

By stepping into the spotlight, Mr. Sloan invited a series of

public condemnations from the OCC and Fed. It was an unusual, if

indirect, show of force that effectively ended his career.

When Mr. Sloan entered the hearing room in the Rayburn office

building on March 12, he shook hands with House Financial Services

Committee members before taking his seat before the microphone.

In the weeks leading up to the hearing, Mr. Sloan had waged a

charm offensive on lawmakers from both parties. He traveled from

office to office, armed with presentations that showed improving

customer-service and employee-satisfaction metrics.

All the big-bank CEOs had been summoned to the Hill after the

Democrats gained control of the House of Representatives in

November. But Mr. Sloan was the only one testifying alone; his

counterparts were all set to appear together at a hearing in

April.

The committee -- led by California Democrat Maxine Waters --

initially asked the CEOs of the six biggest U.S. banks to testify

on March 12, people familiar with the matter said. A number of the

banks declined, saying a date in April, when they planned to be in

Washington for other meetings, would be better, the people

said.

Wells Fargo said Mr. Sloan was available. The bank was eager to

repair its relationship with Washington.

Rep. Waters had made it clear Wells Fargo would be a priority on

her watch. A hearing date was set.

During the hearing, Mr. Sloan faced a barrage of tough questions

from both sides of the aisle. He appeared worn but never lost his

composure, saying repeatedly that the bank was trying hard to

change its ways.

Rep. Waters got the last word, calling on the OCC to consider

removing Mr. Sloan. Dogged by protesters in the audience, Mr. Sloan

approached the dais to shake her hand.

Some lawmakers who had met with Mr. Sloan in the days before the

hearing were frustrated by his answers.

Rep. Brad Sherman (D., Calif.) became irritated during the

hearing after Mr. Sloan declined to take a position on legislation

to protect consumers against unreasonable overdraft fees. "He

bobbed and weaved and filibustered and wouldn't give us a straight

answer," Mr. Sherman said in an interview.

Still, Mr. Sloan had avoided a repeat of Mr. Stumpf's disastrous

appearance before the Senate Banking Committee in 2016. But it

didn't move the needle with regulators.

Minutes after the hearing ended, the OCC released a rare

statement rebuking the bank, saying it was "disappointed with

[Wells Fargo's] performance under our consent orders and its

inability to execute effective corporate governance and a

successful risk management program."

A week later, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell took aim at

the bank's system meant to prevent problems that could harm

customers. The risk-management framework, he said, had experienced

a "remarkably widespread series of breakdowns."

Mr. Powell said the Fed wouldn't lift the bank's asset cap

"until Wells Fargo gets their arms around this, comes forward with

plans, implements those plans, and we're satisfied with what

they've done. And that's not where we are right now."

The harsh words from regulators left Mr. Sloan with little

option but to resign, according to people familiar with the matter.

He stepped down Thursday, and the bank's board is looking for an

outsider to take his place.

"I could not keep myself in a position where I was becoming a

distraction." Mr. Sloan said Thursday.

Within the bank, Mr. Sloan's announcement was met with mixed

emotions. Some took it as a sign that Wells Fargo was finally

moving on from the fake-account scandal, people familiar with the

matter said. In an internal note reviewed by the Journal, the

bank's top wealth-management executive advised employees to stay

"calm and strong."

Others were disturbed, the people said. Washington, they were

convinced, had taken out the CEO of a private-sector company.

Write to Rachel Louise Ensign at rachel.ensign@wsj.com and

Andrew Ackerman at andrew.ackerman@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 30, 2019 09:14 ET (13:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

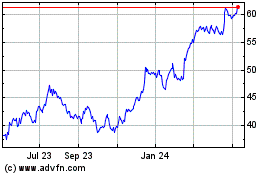

Wells Fargo (NYSE:WFC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Oct 2024 to Nov 2024

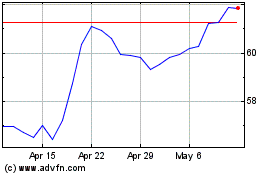

Wells Fargo (NYSE:WFC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Nov 2023 to Nov 2024