By Eliot Brown and Aaron Tilley

For much of the past decade, the San Francisco Bay Area has

strained to absorb the torrid growth of the tech sector. As head

counts of highly paid engineers swelled, housing costs soared,

traffic gridlock rose and homeless tents spread on city

streets.

Now a small-but-prominent roster of tech companies and investors

are doing something about it: leaving.

The region's latest emigrant is database giant Oracle Corp., a

fixture of Silicon Valley for decades that last year signed a

20-year deal to put its name on the San Francisco Giants' stadium,

Oracle Park. The $180 billion tech giant on Friday said it had

changed its headquarters location to Austin from Redwood City,

Calif.

Oracle provided few details, saying it is implementing more

flexible remote-work policies but wouldn't move staff. It follows

an announcement earlier this month by Hewlett Packard Enterprise

Co., another business-technology company with deep roots in Silicon

Valley, that it is moving its headquarters to Houston -- as well as

similar moves by a number of well-known venture capitalists

announced in recent months. Elon Musk, who had long lived in Los

Angeles and commuted to Tesla Inc.'s operations near San Francisco,

last week said he had moved to Texas. And he criticized the

policies of the state as restrictive -- echoing the arguments of

many of those leaving the Bay Area.

These high-profile departures are causing some soul searching in

Silicon Valley -- taking some sheen off the area's reputation as

the unparalleled tech capital. While reasons vary, many moves

appear to have been sparked by the Covid-19 pandemic that has

reshaped notions of where and how we work, and companies, investors

and employees are generally moving to places that are warmer, with

lower taxes and cost of living.

"Covid basically encouraged people to work remotely and

experiment with other places to live," said Keith Rabois, a

well-known San Francisco-based venture capitalist moving to

Miami.

Mr. Rabois, a Republican often at odds with policies enacted by

San Francisco's liberal government, said he was frustrated with

declining quality-of-life issues like homelessness and the state's

relatively high taxes, among other issues, and he realized he could

do his job well from afar.

"It became clear there were much better places to live," he

said.

Despite the moves, Silicon Valley's place in global technology

is still unrivaled. Five of the eight most valuable U.S. companies

are based in the region. Major employers like Facebook Inc. and

Google parent Alphabet Inc. have added office space in the region

even during the pandemic. And the Bay Area has continued to churn

out major new companies that captivate investors. The week of

Oracle's announcement, delivery-company DoorDash Inc. and

home-sharing company Airbnb Inc. went public with soaring

valuations.

Venture-capital funding this year has continued to go to Bay

Area startups at disproportionate levels, even though the pandemic

has made in-person meetings with investors there uncommon.

Once offices reopen, even if a large chunk of workers stay

remote, many investors and executives say the value of proximity is

so high that they expect the region's prominence to continue.

Patrick Eggen, co-founder of the venture-capital firm

Counterpart Ventures, says his firm's location in San Francisco's

South Park neighborhood has been critical to its success -- and

will be after the pandemic.

"My business is all relationship oriented. In-person meetings

are the artery of that existence," he said. "It gives me an edge

being here."

Even if the Bay Area's dominance is reduced, "you still have the

highest concentration of talent, companies and capital," he said.

"The cluster is still here."

That clustering is considered a major reason for Silicon

Valley's dominance. Large companies grow off each other, with

engineers leaving established companies to create their own

startups, and rivals constantly poaching from one another.

Investors often say they are more comfortable funding companies in

their backyards.

Still, as the tech sector has gone from a niche to America's

dominant industry, the region has strained to keep up, leading to

growing discomfort.

Between 2005 and 2019, employment in the five counties that make

up the bulk of the Bay Area grew by 29%, adding 674,000 jobs,

according to California's Employment Development Department. Yet

construction permits were issued for just 211,000 units, according

to the U.S. Census Bureau. Planners say the ratio of new jobs to

new housing units should be around 1.5 to one.

The result has been soaring prices for housing and cost of

living, which in turn fuels ever higher costs for paying

employees.

Well before the pandemic, tech companies began adding offices in

places like Seattle, Nashville and Austin. Salesforce.com Inc.,

whose Salesforce Tower headquarters dominates San Francisco's

skyline, has in recent years put the same name on buildings in

Indianapolis, New York and Chicago. Financial-tech company Stripe

Inc., which had been hiring engineers to work remotely before the

pandemic, this year offered employees $20,000 to move elsewhere --

and accept a reduced salary based on the location.

"There's a finite space in the Valley, and there's a need to

scale and continue to expand," said Aaron Levie, CEO of Box Inc., a

Redwood City, Calif.-based cloud company.

Six years ago, Mr. Levie opened up a small office in Austin.

Now, it is Box's largest outside of Silicon Valley, with several

hundred employees. Given the growing size of the tech sector, he

said, it will need "to attract talent wherever it can."

With a sizable tech workforce, plus lower housing costs and no

state taxes on income or capital gains, Austin has been a popular

destination. Apple Inc. last year said it was adding a large new

facility in the area, and Tesla is building its second U.S. factory

there.

Austin Mayor Steve Adler said in an interview that many of the

tech companies come without being courted. He said he was unaware

of Oracle's plan until Friday, when the company announced it. "As

you start building a critical mass, it feels like there are more

and more people expressing an interest," he said.

Write to Eliot Brown at eliot.brown@wsj.com and Aaron Tilley at

aaron.tilley@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

December 13, 2020 16:29 ET (21:29 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

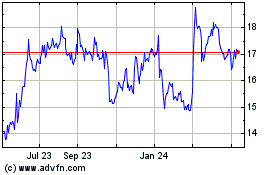

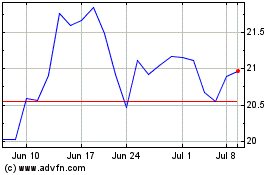

Hewlett Packard Enterprise (NYSE:HPE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Oct 2024 to Nov 2024

Hewlett Packard Enterprise (NYSE:HPE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Nov 2023 to Nov 2024