By Alex Leary

WASHINGTON -- At a June 2016 Business Roundtable meeting of 100

of the nation's top executives, a speaker asked for a show of hands

from those who had dealt with Donald Trump, who would officially

become the Republican presidential nominee the following month. Not

a single hand was raised.

Today, nearly two years after Mr. Trump took office, the

business community is still trying to figure out how to work with

the businessman-turned-president. Progress is being made, in fits

and starts.

Chief executive officers early on were eager to join various

councils created by the White House -- a head-on approach that

collapsed after Mr. Trump's controversial response to a

white-supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Va., last year that

resulted in the death of a peaceful counterprotester.

Since then, individual companies and trade groups have employed

a mix of quiet diplomacy and occasional splashy displays of support

to create an alliance that has produced broad regulatory rollbacks

and curbs on new rule making, as well as the biggest one-time drop

in the corporate tax rate, now the lowest since 1939. Those gains

have come against the backdrop of a booming economy and stock

market, though the latter has wobbled in recent months.

That alliance, however, is being tested anew with Mr. Trump's

provocative moves on trade, tariffs and immigration.

"The uncertainty is terrible," says Carlos Gutierrez, former CEO

of Kellogg Co. and commerce secretary under President George W.

Bush. "Sure, we need to have serious discussion with China, but do

we need to get in a trade war that is going to impact U.S.

companies and consumers?" CEOs, he says, "are on the edge."

Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, a Yale School of Management professor who

conducts regular CEO surveys, sums up the business leaders'

political journey this way: "In the course of two years, CEOs have

moved from skepticism, to fearful concern, to cautious optimism, to

widespread enthusiasm, to disappointment, to guarded fear with

lingering targeted hope."

Fresh whiplash came last week when General Motors Co. said it

would end production at several U.S. factories next year. CEO Mary

Barra, once a member of a presidential advisory council, took the

news directly to Mr. Trump a day before the news became public. The

next day, she attributed the move to shifting consumer taste and a

bet on electric and self-driving vehicles. GM's stock jumped.

But Mr. Trump lashed out, telling The Wall Street Journal that

GM "better damn well open a new plant" in Ohio -- a crucial

election battleground -- and stop making vehicles in China. The

flogging continued the next day, with Mr. Trump threatening on

Twitter to cut off electric-vehicle and other subsidies. This time,

GM's shares fell.

A promising start

At first, CEOs discovered an ally in President Trump, who in

meetings with executives made personal requests for lists of

problem regulations and solicited advice on policies. He charmed

guests with impromptu invitations to visit the Oval Office.

During a meeting in February 2017, Mr. Trump turned to David

Farr, CEO of Emerson Electric Co., and asked him to come up with a

list of regulations the industry found onerous. Within a month, the

National Association of Manufacturers, which Mr. Farr chairs,

submitted a 42-page report.

"That's what most Americans don't get to see, how great our

president is at listening. He's dealing with innumerable issues and

crises and truly values input of U.S. business leaders," Harold

Hamm, chief executive of shale-oil producer Continental Resources

Inc., said last month. "I was drawn to Mr. Trump much like the rest

of the American people. He was not a politician seeking to advance

his career, but rather a businessman who was more interested in

solutions than the political norm."

But the unconventional aspect of his presidency quickly cut both

ways. Mr. Trump's freewheeling Twitter feed, for example, has

complicated relations. In December 2016, before being sworn in, Mr.

Trump shocked Boeing Co. with a complaint about the cost of a

replacement Air Force One, tweeting "Cancel order!"

Meanwhile, CEOs who have publicly praised the president, such as

Under Armour Inc.'s Kevin Plank, stepped into a minefield of

polarized consumer reaction. Mr. Plank called Mr. Trump a "real

asset" to business, amid an uproar over the president's attempts to

impose a targeted travel ban. The company faced boycott calls and

rebukes from customers and its contract athletes. A year later,

after Charlottesville, Mr. Plank was the second executive to resign

from the president's American Manufacturing Council -- eliciting a

new wave of calls for boycotts, this time from Trump

supporters.

Business leaders soon decided that new tactics were needed.

Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg called up Mr. Trump almost

immediately after the Air Force One tweet and sought a face-to-face

meeting. Amid negotiations over the price, Mr. Muilenburg explained

how government security requirements drove the costs, but also

publicly flattered the president as a "tough negotiator" and "a

good businessman."

He opened Boeing's doors for Mr. Trump, throwing a

campaign-style event in February 2017 in South Carolina in which

workers held signs touting American jobs, and he continued to

attend the president's industry roundtables on national-security

matters.

That has afforded Mr. Muilenburg room to pursue other issues --

he played a role in the president's reversal of a campaign pledge

to kill the Export-Import Bank. Mr. Trump's posture toward China, a

rapidly growing market for Boeing, remains problematic for the

company, but Mr. Muilenburg has maintained a positive profile,

extolling the value of a "seat at the table."

Lockheed Martin Corp. CEO Marillyn Hewson has been similarly

nimble, saying she welcomed a discussion about the F-35 fighter-jet

program costs after Mr. Trump complained about them. She has joined

with the White House on attempts to crack down on Chinese theft of

intellectual property. This summer, when the White House held a

showcase of American-made products, Lockheed delivered an F-35 and

an Orion spacecraft to the South Lawn.

"She's tough," the president has said of Ms. Hewson. Mr. Trump

the critic has since become the salesman, helping curry favor for

the F-35 program on Capitol Hill, where costs have been a

bipartisan issue for years. In November, Lockheed was awarded a

contract worth up to $23 billion from the Defense Department to

deliver 255 F-35 jets.

Worker prep

Ms. Hewson has also ensured a role for Lockheed in the White

House's focus on workforce development, pledging millions of

dollars for vocational and trade programs. Businesses are

increasingly concerned about a lack of skilled employees, and

dozens of companies, from Amazon.com Inc. to FedEx Corp. and

Raytheon Co., have been eager participants in the push, spearheaded

by Mr. Trump's daughter, Ivanka. Similarly, many companies joined

efforts to combat the opioid crisis, which has had a ruinous effect

on workers across the country.

Boeing and Lockheed Martin declined to make executives available

for interviews, as did a number of other top corporations, which

have courted Vice President Mike Pence as well.

In August, a year after Charlottesville, Mr. Trump gathered a

group of about 15 CEOs for a dinner at his Bedminster, N.J., golf

resort that served as a sort of reset.

Among those in attendance were Mr. Muilenburg, Fred Smith of

FedEx, Michael Manley of Fiat Chrysler Automobiles NV, Jim Koch of

Boston Beer Co., Mark Weinberger of Ernst & Young and Indra

Nooyi, then CEO of PepsiCo.

Mr. Koch brought Sam Adams beer and toasted the president for

the tax bill, saying a lower corporate tax rate improved

competition with foreign companies. Then came the hangover: Boston

Beer faced its own customer revolt.

Apple Inc.'s Tim Cook has had good results from his interaction

with the president. Mr. Cook, who endured candidate Trump's calls

for a consumer boycott of Apple over its refusal to unlock an

iPhone used by a terrorist attacker in San Bernardino, Calif., has

visited the president at the White House and dined with Mr. Trump

in Bedminster. In these meetings Mr. Cook has pressed an array of

issues, including immigration, something he and the president don't

agree on.

Tariff reprieve

For Mr. Cook, the alliance has resulted in Apple being spared

from tariffs on products made in China, though Mr. Trump floated

possible levies in an interview last week with The Wall Street

Journal.

Other executives have had less success in moving Mr. Trump off

his trade position. Robert Lighthizer, the U.S. trade

representative, visited the Business Roundtable last year and

delivered a tough-luck message, telling the group that its

interests didn't always line up with the interests of the American

worker and that the two sides would be at loggerheads.

After seeing little chance to avoid a trade fight, the business

community pivoted focus and helped persuade the White House to

forestall it until they could get the tax bill through the narrow

Republican majorities in Congress. Their argument: Their coalition

wasn't strong enough to fight on two fronts.

Mr. Leary is a Wall Street Journal reporter in Washington. He

can be reached at alex.leary@wsj.com. Doug Cameron, the Journal's

Chicago deputy bureau chief, contributed to this article.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

December 03, 2018 22:14 ET (03:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

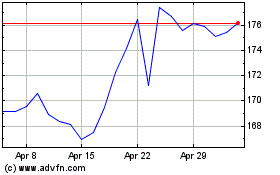

PepsiCo (NASDAQ:PEP)

Historical Stock Chart

From May 2024 to Jun 2024

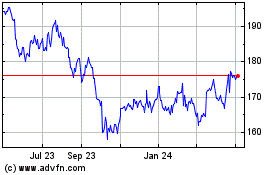

PepsiCo (NASDAQ:PEP)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jun 2023 to Jun 2024