By Catherine Stupp

Governments and companies are planning to introduce mobile

applications that use Bluetooth to track coronavirus infections.

Researchers say the technology keeps users' identifying data

private, but the complexity of working with Bluetooth raises

cybersecurity concerns.

Bluetooth, a widely used technology for connecting devices, has

emerged as the technology of choice for tracking the spread of the

coronavirus, as the U.S. and European countries decide how to

safely reopen businesses in the coming weeks and months. European

governments including France, the U.K. and Germany said in recent

weeks that they are developing Bluetooth-based mobile apps to

notify individuals who came close to someone who has the virus.

Singapore and Australia are already using Bluetooth-based

tracing apps. Apple Inc. and Alphabet Inc.'s Google said this month

they are working on a Bluetooth system that developers can use to

build tracing apps while protecting users' privacy.

Security and privacy researchers say there are advantages, along

with potential risks, to using Bluetooth. It reveals less detailed

information about a person's location than other technologies, such

as GPS. Bluetooth's specifications are several thousand pages long,

and that complexity can lead to mistakes by developers, said Ben

Seri, vice president for research at cybersecurity firm Armis

Inc.

In November, a researcher from the Technical University of

Darmstadt in Germany found a vulnerability in how Bluetooth was

implemented on devices using Google's Android operating system.

Google issued a patch in February. The problem could have allowed

hackers to launch remote cyberattacks.

In 2017, Mr. Seri discovered a security problem in how mobile

devices handled Bluetooth signals. Hackers could have exploited the

bug to move between devices using Bluetooth connections. Apple,

Google and other companies issued patches to fix the problem in

devices' operating systems. Such flaws are becoming less common as

companies improve how they implement Bluetooth, said Mr. Seri.

If many people start using tracing apps, there could be more

devices that enable Bluetooth all the time. Creative hackers might

look for devices with Bluetooth turned on in their vicinity and try

to launch remote cyberattacks, said Eliot Bendinelli, a

technologist at London-based nonprofit Privacy International.

Apple and Google have said app developers that use their

technology must comply with their privacy and security criteria.

For example, users must opt in to share their data. Public health

authorities would receive a list of Bluetooth beacons showing

devices that were in contact with users who have coronavirus.

The app that France plans to deploy by May 11 won't be able to

work on iPhones the way the government intended because Apple

appears to prevent the transfer of data collected by Bluetooth

coronavirus apps from a device to centralized servers, the

country's Digital Minister Cédric O told Bloomberg last week. He

said he asked Apple to change the policy.

Apple and Google declined to comment on France's complaint. A

Google spokesman referred to the two companies' publication last

week of updates to their system that they say will protect privacy

and make it more difficult to identify individuals. This includes

encrypting the Bluetooth metadata that phones share when they

connect using the technology.

Representatives of the companies said Wednesday their technology

will let public-health authorities assign users different risk

levels and tailor the notifications they send to people

accordingly. The risk level will be based on users' proximity and

duration of exposure to known coronavirus carriers, and will be

calculated on users' devices for privacy and security reasons.

Bluetooth connects devices by changing signals periodically to

hide users' unique addresses. The feature is designed to protect

privacy, but it could be possible for data to be exposed when a

mobile phone connects with other devices nearby, according to a

paper published last year by Boston University researchers.

It is unclear whether other apps installed on a phone could

collect data from a coronavirus tracing app, David Starobinski, a

Boston University professor in electrical and computer engineering

who wrote the research, said in an interview. The 2019 paper was

published before the coronavirus outbreak and didn't refer to

contact-tracing apps.

Individuals would be more secure using a second phone for

contact tracing, he said. "Ideally, we'd have a different device

that's more isolated from other services," he said.

Technical limitations

Aside from potential security risks, Bluetooth may not be a

perfect technology for tracing which people have come close enough

to transmit the coronavirus.

Developers of the original Bluetooth protocol said the

technology wasn't designed to generate detailed, reliable data

about proximity between devices. "The accuracy is limited," said

Sven Mattisson, one of the engineers who designed the concept for

Bluetooth in 1995 when he worked at Ericsson AB.

"You might interpret a false contact in a parking lot because

you get such a strong signal back, even though the contact is far

away. But if you're in an office space, you might not receive a

signal," said Mr. Mattisson, who is now an adjunct professor in

microelectronics at Lund University in Sweden. Signals might be

strong in an open space with few people even if they are far apart,

but they may be weaker in a crowded enclosed area.

A Bluetooth-based contact-tracing app that sends a signal when

two users are close to each other might not recognize when they are

separated by a window or walls, the Australian law firm Maddocks

wrote last week in a privacy assessment of the country's app. The

Australian health ministry said in response that it is seeking

advice about the use of Bluetooth from the country's cybersecurity

agency.

But the ubiquity of Bluetooth is an advantage amid a pandemic,

said Jaap Haartsen, who developed the technology with Mr.

Mattisson. It could take years to roll out mobile technology that

could be better suited to tracing contacts, he said. Mr. Haartsen

is now chief scientist for wireless technologies at Plantronics

Inc.'s Poly, a communications services company.

"It was not made for tracing, but at least it can give an

indication [of] which other phones have been in close range," he

said in an email.

Write to Catherine Stupp at Catherine.Stupp@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 30, 2020 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

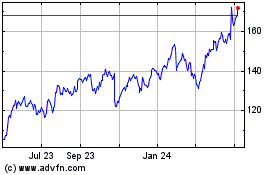

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOGL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Oct 2024 to Nov 2024

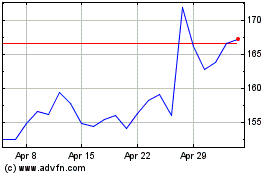

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOGL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Nov 2023 to Nov 2024