In this month’s employment report, the two different surveys seem

to be telling two diametrically opposed stories. The establishment

survey paints a picture of fairly robust -- and certainly

better than expected -- job growth. The Household survey is much

more downbeat and shows increasing levels of unemployment for

almost every major demographic group.

A divergence between the two surveys is hardly unprecedented, and

for the first three months of the year, the household survey was

noticeably more upbeat than the establishment survey. Over the

longer term the two do tend to converge, and the differences tend

to come out in the wash.

Demographics of Joblessness

This recession has hit men harder than it has hit women. However,

over the past year, things seem to be “evening out” between the

genders, and this month both slipped back. In April, the

unemployment rate for adult men (over 20) rose to 8.8% from 8.6% in

March, but down from 9.9% as recently as November. It is down from

10.0% a year ago.

A bit of the year-over-year decline is an illusion though as the

participation rate for men fell from 74.6% a year ago to 73.4% in

April, unchanged since February (for a fuller discussion of the

importance of the participation and employment rates see "Jobs

Report in Depth, Part 1"). The employment rate for men fell to

66.9% from 67.0% in March, and down from 67.1% a year

ago.

For women, the unemployment rate rose to 7.9% in April, up from

7.7% in March, but down from 8.2% a year ago. The participation

rate was 60.0%, since January, but down from 60.6% a year ago. The

employment rate fell to 55.3% from 55.4% in March, and is below the

55.7% rate a year ago. For both sexes, there has been a real

year-over-year improvement in the employment situation, but it is

not as big as just looking at the unemployment rates would

indicate.

In the overall big picture, men have fared far worse than women in

this downturn. There are two possible reasons for that. The first

is that the industries that have been particularly hard hit in this

downturn tend to be far more male dominated than the industries

that have skated though this recession more or less unscathed.

The most glaring example of this would be the construction industry

versus the health care industry (more on the industry breakdowns

below). The second explanation is that on average, women tend to

still be paid far less than men do, and employers might be more

prone to let their relatively high priced male employees go first

before their cheaper female employees. The industry effect is

probably the bigger one, but the two are not mutually exclusive and

both might be playing a role.

Teen Employment

Teens, regardless of gender have had a very hard time of it in this

recession. Just go to a

McDonald's (MCD) and you

will see this for yourself. Normally the blemishes you see on the

cashier's face is acne, not wrinkles and age spots as is the case

now.

Things got even worse for teens in April. The teen unemployment

rate rose to 24.9% from 24.5% in March, but is down from 25.4% a

year ago. Things are even worse than they sound. The participation

rate fell to 33.7% from 34.1% in March, and is well below the 35.8%

rate a year ago. The percentage of teens that actually have a job

fell to 25.3% from 25.8% in March, and is down from 26.7% a year

ago.

While for the most part the earnings from teen jobs tend to go

towards clothes from

Abercrombie & Fitch (ANF)

and other teen clothing stores, for many it is a significant part

of paying for college. Also when teens work, they learn important

job skills, such as the importance of actually showing up, and

doing so on time. The extremely low levels of teens working is not

a good sign for the future.

Racial Breakdown

Not surprisingly, Whites have a lower unemployment rates that do

Blacks or Hispanics. This month, the picture deteriorated for all.

The White unemployment rate rose to 8.0% from 7.9%, but is down

from 9.0% a year ago. The participation rate rose to 64.7% in

April, from 64.6% in March, though it is down from 65.6% a year

ago.

The employment rate for Whites was unchanged at 59.5% from last

month but is down from the year-ago level of 59.7%. The rise in the

unemployment rate from last month is a bit of an illusion due to

the rise in the participations rate, but then so is the decline

from a year ago due to the fall in the participation rate.

The unemployment rate for Blacks rose to 16.1% from 15.5% in March,

but is below the 16.5% a year ago level. For the month, the

participation rate for Blacks was unchanged at 61.5%, so the

monthly deterioration is as bad as it appears. A year ago the

participation rate was 62.8%. Thus there has been no real

improvement in the employment situation for Blacks over the last

year.

The employment rate for Blacks fell to 51.5% from 51.9% in March,

and is down from 52.4% a year ago. The unemployment rate is 101.3%

higher than for Whites, and the employment rate is 13.4% lower

(51.5% vs. 59.5%). The participation rate is just 4.9% lower. A

year ago the participation rate was 4.3% lower and the employment

rate was 12.2% lower. A year ago the unemployment rate for Blacks

was 83.3% higher than the White unemployment rate.

For Hispanics, the unemployment rate in February jumped to 11.8%

from 11.3% last month but down from 12.4% last year. The monthly

deterioration is only partly an illusion. The participation rate

rose to 66.6% from 66.4% in March and from 66.1% in February. On

the other hand, part of the year over year improvement though is an

illusion as the participation rate is down from the 67.7% level

last year.

The employment rate slipped to 58.7% from 58.9% last month. A year

ago, the Hispanic employment rate was 59.3%. The participation rate

by Hispanics is actually 2.9% higher than for Whites, but a year

ago it was 3.2% higher than for Whites. The employment rate is 1.3%

lower, while a year ago it was 0.1% lower than for Whites. Over the

last year the unemployment rate has moved from being 37.7% higher

than the White unemployment rate to 47.5% higher than for

Whites.

Stay in School

The unemployment rate for high school dropouts fell to 13.7%

from13.9% in February and from 14.2% in January. It is down from

the year-ago level of 14.4%. Again, the monthly improvement is

actually better than it appears, but the year over year decline is

partly an illusion.

The participation rate amongst the dropouts rose to 46.1% from

45.5% last month and from 45.1% in January but is down from the

46.3% level of a year ago. The percentage of high school dropouts

actually employed rose to 39.8% from 39.2% last month and from

37.2% January and is up slightly from 39.7% a year ago.

I should note here that the numbers by level of education refer to

people over age 24, and so are not directly comparable to some of

the other numbers. The overall unemployment rate for people over 24

years old was 7.6%, up from 7.4% in March but down from 8.3% a year

ago.

Just finishing high school or getting your GED substantially

increases your odds of having a job. The unemployment rate for high

school grads (with no college) was rose to 9.7% from 9.5%. in

March. It is down from the 10.5% rate a year ago. In all three

months, the level was still far below that for dropouts. This month

the unemployment rate for dropouts was 50.5% higher than for those

who at least finished high school.

The participation rate for high school grads rose to 60.9% from

60.0% last month. A year ago it was 62.4%. Thus, the improvement

from last year is somewhat of an illusion. However, month to month,

things actually improved, rather than deteriorated as the

unemployment rate alone would indicate. The employment rate for

high school grads rose to 54.6% from 54.4% in March but is down

from 55.8% a year ago. Note that the participation rate and the

employment rate are much higher for High School Grads than for

Dropouts.

Those that went to college but did not finish, or only got an

Associates degree, had an unemployment rate of 7.5%, up from 7.4%

in March, and down from 8.3% a year ago. The participation rate for

Associate Degree holders was unchanged at 69.7% but is down

from 71.0% a year ago. The employment rate dipped to 64.5% from

64.6% in March but is down from the 65.1% level of a year ago.

For those who stay in school to get their BA (or higher) the

unemployment rate rose to 4.5% from 4.4% in March, and is down from

4.8% a year ago. The participation rate rose to 77.0% from 76.9% in

March, which explains the rise in the unemployment rate. The

participation rate is down from 77.2% a year ago. The percentage of

college grads with jobs was unchanged at 73.5%, both from a month

and a year ago.

The next graph (from this source) is unfortunately not updated with

the April data, but shows the long term history of unemployment by

level of education. While the level of unemployment is always

higher the less education one has, the relatively uneducated really

get hit hard when the economy turns south.

The unemployment rate for people 20-24, those who are just entering

the full time workforce was 14.9% down from 15.0, and down from

17.1% a year ago. This decline is good news. If these people cannot

get jobs, they tend to remain living with Mom and Dad. This slows

the rate of household formation, and hence the demand for housing.

That makes it difficult for the economy to absorb the huge housing

inventory overhang.

Normally housing is the locomotive that pulls the economy out of

recessions. That locomotive is still derailed, and it is the

principal reason that this recovery has been so sluggish. The

improvement in the unemployment rate for these folks is good news,

but the level is still extremely problematic.

The unemployment rate for those a bit older, the 25 to 34 year old

cohort, which is the prime age for first time home ownership, moved

the other way, rising to 9.5% from 9.1% last month but down from

10.2% a year ago. Lowering the unemployment rate amongst these

people will be a key to resolving the housing problem. We are

making progress, but still have a long way to go. Several studies

have shown that not being able to get a job right after finishing

school hurts people not only short term, but the effects lasts

their entire working career.

Where the Jobs Are (and Are Not)

The private sector actually added more than the total number of

jobs again this month. State and local governments laid off 24,000

workers, and have trimmed their payrolls by 272,000 over the last

year. Actually it is mostly at the local government level where the

declines are occurring. Local government employment was down by

14,000 on the month, and is down by 245,000 from a year ago. The

number of state employees was down 8,000 on the month and is down

by 27,000 over the last year.

In looking at the effectiveness of the stimulus program from the

Federal government, one should keep in mind the massive

anti-stimulus effect of budget cuts and tax increases (mostly

budget cuts) at the state and local levels of government. Federal

Government employment was down 2,000 for the month but is down by

404,000 over the past year (mostly due to the hiring of temporary

Census workers last year).

Within local government, education jobs were down by 4,700 for the

month and are down by 133,700 over the last year. Given the huge

disparity in the unemployment rate between the uneducated and the

highly educated that I discussed above, one has to seriously

question the wisdom of laying off so many K-12 teachers. How are we

going to compete in the future against countries that actually

think it is a good thing to educate their future workforce?

The private sector added 268,000 jobs, on top of an increase of

231,000 jobs in March (revised up from 230,000). In February the

private sector added 261,000 jobs (revised up from 240,000, and an

initial read of 222,000). The private sector job growth over the

last three months is certainly respectable, averaging 253,300.

That’s good, but hardly great, especially coming out of a deep

recession.

The April number was far above the consensus expectations of

200,000 private jobs gained. The upward revisions to previous

months have been happening regularly for several months now. That

makes it likely that when the May jobs report comes out, the April

numbers will also be revised higher. I would not be surprised if

the March numbers are also revised up again next month as well.

This is the 17th straight month that the private sector has added

jobs, with a total increase of 1.717 million over the last year. In

a normal year, that would be a great showing, but we lost over 8

million jobs in the Great Recession, so we still have our work cut

out for us.

Within the private sector, the goods producing sector gained 44,000

jobs, on top of a gain of 37,000 in March (revised up from 31,000).

Over the last year, employment in the goods producing sector are up

235,000. The construction industry lost 5,000 jobs, after gaining

2,000 (revised from a loss of 1,000) last month. This marks three

straight months of construction jobs gained (after revisions).

The construction industry has been particularly hard hit in this

downturn, accounting for about 30% of all the jobs lost, even

though at the start of the recession it accounted for less than 6%

of the total jobs in the country. As these jobs generally do not

require a lot of formal education, the demolition of construction

helps explain why the unemployment situation is so dire for those

who never went to college. As a male dominated industry, it also

helps explain why this recession has been so much tougher on men

than it has been on women.

Employment in Construction peaked before the rest of the economy,

in April 2006. Since then, we have lost 2.212 million construction

jobs. Most of the decline though happened after the overall private

sector jobs peaked in December 2007, and since then Construction

jobs are down by 2.202 million, or 28.5%.

Since the peak, overall private sector employment is down by 6.748

million. In other words, this one industry is directly responsible

for 32.6% of all job losses since the end of 2007, even though it

was responsible for just 6.47% of all private sector jobs in

December 2007.

Manufacturing gained 29,000 jobs, on top of 22,000 gained in March

(revised from up 17,000). Manufacturing employment has been in a

secular decline for about 30 years, but it has actually fared

pretty well over the last year or so. The peak in manufacturing

jobs was way back in July of 1979 at 19.531 million.

By the time the Great Recession started in December 2007, the

number of manufacturing jobs was already down to 13.740 million.

The low in manufacturing jobs was in December 2009 at 11.456

million, and since then we have gained back 250,000 of those jobs.

Still, relative to the start of the Great Recession manufacturing

jobs are down by 1.764 million, representing 26.1% of all job

losses from the peak.

Service Sector

The service sector gained 224,000 jobs in the month, up from an

increase of 194,000 in March (revised from a gain of 199,000) and

from a gain of 180,000 in February (revised from 167,000). Relative

to a year ago, private service sector jobs are up by 1.482 million,

but are still off by 3.799 million from the start of the Great

Recession.

One of the biggest contributors to service sector jobs, as always,

was the health care industry which added 41,800 jobs. The health

care industry has not had a single down month in terms of

employment in the entire downturn. The health care industry has a

far higher proportion of women working in it than does the economy

as a whole, and this is a big part of the reason that the

unemployment rate for women is so much lower than that for men.

Temporary Workers

Of particular interest is the increase in temporary workers. Those

jobs fell by 2,300 in April after rising 34,400 (revised from

64,100) in March. It is not that being a temp is the greatest or

highest paying job in the world that makes them of particular

interest. It is because they are a good leading indicator of future

employment trends.

When during a downturn an employer first sees a pick-up in demand,

he will not know if it is just a temporary blip, or the start of a

real recovery. Thus he is going to be hesitant to take the time and

expense of bringing on new workers who will just have to be laid

off it if does turn out to be just a blip. The first thing she is

going to do is work the existing workforce harder. This is

particularly is hours have been previously cut back due to slow

demand.

The flat trend in the average work week is not a very good sign in

that regard. Working more hours means more income, and thus more

spending by hourly employees. The second thing an employer will do

when faced with an increase in demand is going to be to call a temp

agency. Only when the employer is reasonably sure that the upturn

is for real and will last will he figure that it is worth bringing

on a full-time permanent employee.

However, temp jobs have been trending higher since August 2009, and

one would think that we would be starting to see those translating

into permanent jobs at a faster rate at this point. That disconnect

could be pointing to some sort of structural shift in the

employment market, but it is too early to say. Since 8/09 the

number of Temps is up by 509,900 or 29.1%, but is still 14.6% below

the level at the start of the Great Recession.

The number of people working part time for economic reasons, in

other words because that is all they could find, or because their

previously full-time job has had its hours cut back, rose to 8.600

million, up 167,000 from March but down 546,000 from a year ago.

The recent bounce in that number is bad news. It can be seen in the

rise of the “underemployment rate” (U-6 for you wonks out there)

which climbed to 15.9% from 15.7% last month but down from 17.0% a

year ago. That is still a very high rate.

After all, if you are used to working 40 hours a week, but have

been cut back to just 20 hours a week, you might not be unemployed,

but economically you are still struggling. Those involuntary

part-time workers seem to be taking the jobs of those who want to

work part time. The number of people who were working part time

because that is what they want to do increased by 167,000 for the

month, and down 753,000 from a year ago.

Lots of Crosscurrents

Overall, this was a very solid report. However, when you look below

the surface, it is not as good as the headlines suggest. The

internals of the report were on the weak side. The unemployment

rate rise was not due to a rise in the participation rate, it was

unchanged. If it had been a rising participation rate, one could

safely ignore the bump in the unemployment rate. A rising

participation rate would be a good sign for the economy even if it

raised the unemployment rate.

The 0.2 point increase in the unemployment rate puts us back to

where we were in January. The January rate though was after a

dramatic 0.4 point drop on top of a 0.4 point drop in December.

That was the best two month decline since 1958. The job creation

pace was a much higher than expected, particularly on the private

sector side. That, however, is only true of the establishment

survey, the household survey indicates an actual decline in

employment.

The cuts in government employment were bit larger than what the

consensus was looking for, but not exactly shocking, and the miss

was offset by a revision to last months numbers. All things

considered, it is better to see the job creation in the private

sector, but those public sector jobs are held by real people.

Wal-Mart (WMT) does not ask if you are in the

public or private sector at the checkout counter.

The pace of job creation is starting to put a dent in the huge

numbers of people who are without work and want it. Yes, the pace

of job creation in this recovery is much better than it was coming

out of the last recession, but that is pretty cold comfort for

those who are being forced into abject poverty because they can’t

find work despite months and months of pounding the pavement (or

the keyboard as is more likely these days).

Officially we are now 22 months into an economic recovery, and the

economy has added a total of 926,000 private sector jobs since

then. From the low in December 2009, we have added 2.027 million

jobs. At the same point after the 2001 recession was over, the

economy had actually lost an additional 1.154 million jobs in the

private sector. Twenty two months after the 1990-91 recession

ended, we had only added 777,000 private jobs. Most of those people

are really not going to be all that interested in how the pace of

this recovery compares to the pace of the recovery following the

2001 downturn, they just want a job that can support their

family.

However, the point is that it is not unusual for the pace of job

creation to be slow even after the recession has been over for

awhile. The damage done by this downturn was far deeper and more

extensive than in those downturns. The next graph below (also from

http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/) shows just how deep and nasty

this downturn was relative to all the post war recessions that came

before it.

By this long after the previous peak in employment, in every case

but one (2001), the economy had fully recovered and had more total

jobs than when the recession started. While clearly we have started

the upturn, with or without census hiring, it is going to take a

very long, long time before we surpass the total number of jobs the

economy (both private and government) had back in January of 2008

(137.996 million). We are still 7.258 million lower than that

level, so at the March pace, it would take 34 more months to get

back there, in other words, not until January 2014.

The Anti-Stimulus

The Anti-Stimulus

The fiscal stimulus, as helpful as it has been in preventing a much

deeper downturn and giving us the start of a recovery, is starting

to wear off. This can clearly be seen in the reduction in State and

especially Local government employment. Over the last year, total

government employment is down by 404,000 or 1.79% while private

sector employment is up by 1.717 million, or 1.60%.

Local government employment is down by 1.60% over the last year.

The year-over-year decline in total government is a bit inflated by

the loss of temporary census workers that were employed a year ago.

That will be a bigger issue next month.

Most localities really don’t have a choice but to lay people off as

salaries are usually the biggest part of their budgets, and they

can not run operating deficits. A big part of the ARRA was actually

aid to states and localities to prevent these sorts of lay offs

from happening, but now that funding is running out.

If not for the ARRA the cuts we are seeing now would have happened

earlier. Given the extremely high duration of unemployment numbers,

it is likely that many if most of those folks would still be out of

work.

Lower aggregate demand is going to hurt, not help, business

confidence. However, increased confidence is the key part of the

reasoning of these people for cutting jobs to increase employment.

It sure has not worked out that way in the U.K. which has adopted

this “stimulus by austerity approach” where business confidence

recently fell to a two year low, and the economy shrank in the

fourth quarter.

It rebounded a little bit in the first quarter, but its growth rate

is only about one fourth of what ours was in the first quarter, and

we were not exactly booming in the first quarter. Has the

confidence fairy shown up in Ireland, Greece or Portugal, all of

which have been under tough austerity regimes? It sure doesn’t look

like it to me.

The final graph shows the year over year percentage change in

Private and Government employment over the last 30 years. The big

spike in government employment almost a year ago and in 2000 is due

to temporary census hiring. Note that there has been no secular

trend towards government employment growing more quickly than that

of private employment.

One of the arguments about the relative level of private versus

public sector pay has been that public sector employees should be

paid less because they have greater job security. While it is true

that government employment does not fall as much during recessions,

given the experience over the last year, one has to ask, what job

security for public sector employees?

Note that in the 2001 recession, the overall drop in employment was

much more greatly cushioned by increasing government employment

than has been the case in the Great Recession. Also keep in mind

that the population has been growing about 1.0% per year over the

last 30 years.

While it is true that you don’t want to raise taxes in a recession

or in an incipient recovery, it is equally true that you don’t want

to cut government spending. Tax increases and spending cuts are

both forms of fiscal contraction. Not all tax cuts or spending are

equal in terms of stimulating the economy and creating jobs.

The cut in the payroll tax is likely to be quite effective in

stimulating the economy since it will result in higher take home

pay to people who are likely to spend it quickly. Cuts in spending

on overseas adventures in Iraq and Afghanistan would not do much

damage to domestic employment but the spending there is not

primarily about domestic employment.

Cuts in social safety net spending, which is apparently high on the

agenda of those pushing to cut spending right away is likely to be

a major drag on the economy and job creation. The recent budget

cuts agreed to prevent a government shutdown are likely to be a

significant drag on job creation for the lest of the

year.

While clearly we need to address the long-term structural deficit,

slashing away right now on spending is deeply misguided. It will

not bring in anything near the advertised reduction in the deficit.

They will cause enormous pain amongst the most vulnerable people in

our society.

We still have 13.747 million unemployed. Getting them back to work

should be our first priority. As they get jobs, they will have

income, and thus start to pay income taxes again. That in it self

would help bring the deficit back down. After all, a big part of

the deficit problem, particularly in the short term, is that tax

revenues are depressed by the weak economy.

Federal tax collections are, as a share of GDP, near their lowest

point in 60 years. That is also true of State and Local tax

collections, and if anything more so. There is plenty of overlap in

many government programs. Cutting the duplication is fine, but that

money should be channeled into the most effective programs, not

simply cut.

Huge spending cuts to domestic programs will slow the economy, but

it seems to have gathered enough momentum that we are not likely to

fall into a double-dip recession. Still, the cuts are likely to

keep us in the purgatory of a pseudo-recovery, one where the

economy is growing but not producing a lot of jobs, much longer

than needs to be the case.

Unemployment is, to my mind, the biggest economic problem we face.

It is doing far more damage than inflation at this point.

ABERCROMBIE (ANF): Free Stock Analysis Report

MCDONALDS CORP (MCD): Free Stock Analysis Report

WAL-MART STORES (WMT): Free Stock Analysis Report

Zacks Investment Research

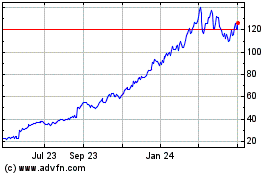

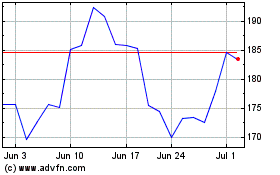

Abercrombie and Fitch (NYSE:ANF)

Historical Stock Chart

From Oct 2024 to Nov 2024

Abercrombie and Fitch (NYSE:ANF)

Historical Stock Chart

From Nov 2023 to Nov 2024