By Sam Schechner

A pizza shop needs your address to deliver your pizza. A chat

app service needs your selfie if you want to send it to friends.

But do internet giants like Facebook and Google really need a list

of websites you recently visited?

A battle is looming in Europe over what information Facebook

Inc., Alphabet Inc.'s Google and other companies can demand from

you. It boils down to what they really need to know -- a debate

that could end up in courts for years with the potential to weaken

either the European Union's new data-privacy law or the business

models of ad-reliant giants like Facebook and Google.

The EU's new privacy law, which goes into effect on May 25,

forbids companies from forcing users to turn over personal

information as a condition of using their services. Does that mean

you can simply say, "No, thanks," to any data collection and still

use Facebook? Not exactly.

There are many exceptions in which companies can still collect

data, such as when that information is necessary to fulfill a

contract with you. That has set the stage in Europe for a battle

over what is truly necessary, and when consent is "freely given,"

regulators and privacy lawyers say.

"The crux of this argument is going to be the legitimacy of the

behavioral advertising business model," said Omer Tene, vice

president and chief knowledge officer for the International

Association of Privacy Professionals. "Behavioral advertising" is

the name for the business, worth tens of billions of dollars per

year, that allows companies to show users targeted advertising

based on their internet activity.

In recent weeks, Facebook has continued work to comply with the

new law -- called the General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR

-- in part by asking users in the EU to opt in to being shown

targeted advertising using data gathered from their activity, such

as web browsing or purchasing information. But when it comes to

authorizing Facebook to collect that data, the company now gives

users a stark choice: agree to its new terms of service or delete

their accounts.

"If you don't accept these, you can't continue to use Facebook,"

a pop-up says of the company's terms and conditions.

Facebook says the data it collects is necessary to fulfill its

contract with users to provide "a personalized experience." The

company says it offers prominent options to control how that data

is used, but that as a data-driven business, it needs to collect

information about its users to function.

"There are certain elements of the service which are core to

providing it and which people can't opt out of entirely, like ads,"

said Stephen Deadman, Facebook's global deputy chief privacy

officer. "There's no point in buying a car and then saying you want

it without the wheels. You can choose different kinds of wheels,

but you need wheels."

Several regulators, including Ireland's Data Protection

Commissioner -- the lead privacy regulator in Europe for Facebook

because that is where it has its base in the EU -- say they are

digging into the decision by companies like Facebook to rely on

contractual necessity to justify the collection or processing of

some data under GDPR.

A spokesman for the Irish regulator said it is "unlikely" that

contractual necessity would pass muster for "collection and

processing of personal data arising from tracking off-platform" --

that is, on sites or apps other than those belonging to a

particular service provider.

"What is really necessary for the performance of the contract

between the users and Facebook?" asked Johannes Caspar, the privacy

regulator for the city of Hamburg, Germany. That is "one of the

crucial questions which we will have to answer under the GDPR."

Google, for its part, issued a new privacy policy on Friday that

outlines how the company collects data about users, including

location and data from other apps and sites that use Google

services. The company has added new controls, such as the ability

to mute an ad that is following a user across the web, and has

reorganized existing controls to turn off features like location

history, but it isn't possible to opt out of all data

collection.

Verizon Communications Inc.'s Oath, which includes Yahoo and

AOL, says in its new European privacy policy that if users withdraw

their consent to collecting their data -- including web-browsing

habits or location data -- that they "may not have access to all

(or any) of our services."

"Processing of your information for the purposes of personalised

content and ads is a necessary part of the services we provide,"

the policy explains.

A spokesman for Oath declined to comment.

Privacy-rights advocacy groups plan to raise this issue, among

others, once GDPR goes into effect. The new law gives consumer

groups the ability to lodge collective complaints, akin to

class-action lawsuits, before privacy regulators or national

courts. France's La Quadrature du Net, a digital-rights advocacy

group, says that it is readying a series of complaints against

large tech companies on the question of whether consent is freely

given. Noyb, another privacy advocacy group founded by privacy

activist Max Schrems, is raising money specifically for the purpose

of filing complaints under the law.

"There will be many, many situations where someone will say, 'My

consent isn't free,' and the service provider will say, 'But you

accepted the terms and conditions,'" said Eduardo Ustaran, a

privacy lawyer for Hogan Lovells. "All of these legal concepts will

be scrutinized to death for years to come."

Write to Sam Schechner at sam.schechner@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 11, 2018 05:46 ET (09:46 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

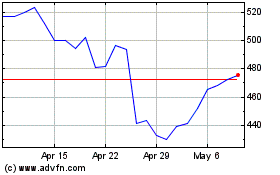

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jun 2024 to Jul 2024

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jul 2023 to Jul 2024