A wave of money fleeing low or negative interest rates overseas

is helping to push down long-term Treasury yields, hobbling a

popular market gauge of U.S. economic health.

The "yield curve" measuring the premium investors pay to hold

10-year U.S. government bonds instead of two-year notes on Tuesday

declined to 0.94 percentage point, the lowest since December 2007.

A year ago, the gap was 1.65 points.

The curve now is said to be flattening, a condition that bears

scrutiny because it could lead to an "inverted" yield curve, in

which short-term rates exceed long-term ones. The U.S. yield curve

inverted in June 2007, shortly before the financial crisis, and in

December 2000, ahead of the 2001 downturn.

Yet some traders and portfolio managers caution that the yield

curve's predictive value may have fallen victim to the age of easy

money, in which global financial flows dwarf the economic trends

that market indicators have long been taken to illuminate.

While many U.S. investors doubt the 10-year Treasury is a

bargain at its recent yield of 1.75%, investors in Europe, Japan

and elsewhere have been large buyers, thanks to the even lower

yields available in their home countries. The pool of

negative-yield bonds hit $9 trillion this month.

The U.S. yield curve is "distorted because of negative interest

rates abroad," said Torsten Slok, chief international economist at

Deutsche Bank Securities.

The failure of U.S. yields to increase in recent months even as

the early year recession scare ebbed has struck many investors as a

sign of foreign capital's impact.

The 10-year yield has ticked lower this month, even as U.S.

retail sales and consumer-sentiment data showed strength and the

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta's GDPNow forecasting service

predicted that second-quarter U.S. economic growth would hit 2.5%.

Stronger data is typically associated with higher bond yields,

because faster economic growth tends to push up inflation.

Craig Brothers, a portfolio manager at Bel Air Investment

Advisors, still keeps measures of the yield curve prominently

displayed on his Bloomberg terminal. But he looks at it less as an

indicator of the economy than as a measure of where investors are

putting money.

"The bond market had better predictive powers in the past than

it does now," said Mr. Brothers, who manages $3 billion of mostly

municipal bonds in Los Angeles.

Other factors play a role, too. The yield curve tends to flatten

early in a Federal Reserve tightening cycle, as short-term yields

rise in response to prospective rate increases while long-term

yields rise more slowly alongside the gathering pace of economic

activity.

About half of the flattening over the past year is because of an

increase in the two-year rate, reflecting expectations for Fed rate

increases this year. The two-year Treasury traded recently at

0.82%, up from 0.55% a year earlier.

Momentum also plays a role. Bond trading increasingly is driven

by hedge funds and principal trading firms using superfast

computers. One popular strategy is known as trend following, which

can lead to a cycle in which bond purchases drive down yields,

begetting further purchases that further drive down yields and so

on.

Traders say that while this process can push yields down further

than economic considerations would seem to demand, the resulting

gap is vulnerable to sudden reversals.

"The flattening yield-curve trade is crowded," said Stanley Sun,

interest rates strategist at Nomura Securities International in New

York.

Another underrated factor: diminished supply of Treasurys as

improving U.S. economic health reduced government-funding needs. In

April 2016, net issuance of Treasury notes and bonds was negative

for the first time since 2008, according to Mr. Slok at Deutsche

Bank Securities.

History underlines how difficult it can be to get a handle on

the swirling dynamics of this market.

A decade ago, the U.S. was running larger and larger

current-account deficits and many government bonds were being

purchased by China, which at the time was using U.S. Treasury

purchases to help hold down the value of its currency, the yuan,

and make its exports more competitive on global markets.

This arrangement fueled fears that the U.S. would be vulnerable

to a financing crisis if China began selling its holdings, an

argument that bearish bond investors contended would vindicate

Treasury short sales.

Those concerns came to naught in the financial meltdown of 2008,

which instead ignited a massive rally in safe bond prices.

Eight years later, China is selling its Treasurys, but few

expect yields to spike imminently, reflecting in part the

deflationary concerns driving the economic slowdown in the world's

most-populous nation. Meanwhile private investors have stepped into

the breach.

Foreign central banks net sold $302 billion U.S. Treasury notes

and bonds over the past 12 months through March this year,

according to Deutsche Bank Securities. Foreign private investors

net bought $317 billion.

Don Ellenberger, a fixed income portfolio manager at Federated

Investors, says long-term bond yields will likely remain low as the

world struggles to adjust to soft growth, even without a U.S.

recession.

"My thought is that we are going to continue to see the curve

flatten, but it is going to be a slow grind over a longer period of

time," he said.

Write to Min Zeng at min.zeng@wsj.com and Ben Eisen at

ben.eisen@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 17, 2016 15:45 ET (19:45 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

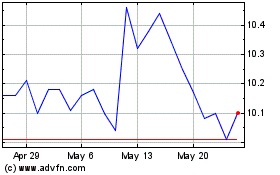

Pacific Current (ASX:PAC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jan 2025 to Feb 2025

Pacific Current (ASX:PAC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Feb 2024 to Feb 2025