UPDATE: Financial Winners In Senate Bill Dodged The Bullets

May 21 2010 - 1:26PM

Dow Jones News

The winners after the U.S. Senate passed financial overhaul

legislation are the industries that managed to avoid being

losers.

Insurers, hedge funds, derivatives exchanges and money managers

avoided most of the worst of the Senate's sweeping proposals, which

were approved late Thursday.

For big banks, regional banks and consumer lenders, not so

much.

"This is not some bump in the road where we go back to business

as usual in six months," said attorney Douglas Landy, head of U.S.

banking practice at Allen & Overy. "This is a very fundamental

change in the way U.S. banks operate, from raising capital to how

they operate and what they invest in."

To become law, the Senate's provisions must be reconciled with

the House of Representative's financial overhaul legislation passed

in December.

By contrast to the fallout for banks, the Senate bill's various

provisions imply small, even incremental, changes for insurance

companies, independent hedge funds and mutual funds--in part

because most policymakers don't blame them for causing the

crisis.

There could be some big changes for hedge funds, for

example--that is, those owned by banks. A key element of the Senate

bill, known as the Volcker Rule after former Fed chief Paul

Volcker, restricts banks from investing in or sponsoring hedge

funds. A relatively light consequence for hedge funds broadly is

that those with more than $100 million must register with the

Securities and Exchange Commission as investment advisers and

report their trades and portfolios to the agency.

If the Volcker Rule ends up becoming law, it could be a boon for

standalone funds. They would face less competition from bank-owned

funds; moreover, the investor bases of those bank-owned funds could

get spooked and flock to other funds. The Senate's light touch on

hedge funds reflects an about-face from the Wall Street crisis of

1998, when hedge fund Long Term Capital Management, rather than a

bank, threatened to sink financial markets worldwide.

The insurance industry avoids any major hits should the Senate's

bill become law. The Senate bill establishes a federal Office of

National Insurance, which insurers have long favored, and which

would advise the president and Congress on insurance issues and

play a key role in international agreements.

Even though many mutual fund investors suffered losses when

markets careened during the crisis, mutual-fund managers were

rarely considered responsible in causing it. Fund management

companies didn't appear to be an express target of the Senate

bill.

The industry complained, however, that it was at risk from

spillover effects of legislation, despite assurances Sen. Scott

Brown (R., Mass) received from House Financial Services Committee

Chairman Barney Frank (D., Mass.) that big companies like Fidelity

Investments wouldn't be exposed to more regulation. Paul Schott

Stevens, chief executive of the Investment Company Institute, a

trade group, said funds could be subject to "bank-like regulation,

in the unlikely event that regulators deem a mutual fund a source

of 'systemic risk.'"

One clear winner could be the derivatives exchange operators CME

Group Inc. (CME) and IntercontinentalExchange Inc. (ICE), which

operate clearinghouses where companies could be forced to clear

their derivatives trades.

Banks and consumer lenders, by contrast, found far less help

from the Senate ranks as lawmakers finalized the bill.

Although Republicans worked to defeat even more restrictive

Volcker Rule language, banks could face strong curbs on the "swipe"

fees they charge to businesses who accept debit cards. Consumer

lenders could also be forced to deal with regulations from an

independent Consumer Financial Protection agency, which both the

House and Senate bills propose.

Moreover, a strong provision by Arkansas Sen. Blanche Lincoln, a

Democrat--which shocked some observers by surviving Senate

horse-trading, despite opposition from government officials--would

make it nearly impossible for Wall Street banks to keep their

lucrative derivatives units. Some observers still expect this

provision to eventually be watered down or removed.

The Senate bill could also force some banks to go through

changes in their capital. Some trust preferred shares might no

longer contribute to key bank capital ratios, which might require

tough negotiations between banks and investors in these shares over

their eventual fate.

The restrictions on capital, coupled with the bill's various

other measures, could mean jarring changes for banks and their

investors.

Said Steve McBee of lobbyist firm McBee Strategic Consulting:

"Senate passage yesterday of financial regulatory reform means the

most sweeping reform of our financial system is one step closer to

enactment."

-By Marshall Eckblad and Erik Holm, Dow Jones Newswires;

212-416-2156; marshall.eckblad@dowjones.com

(Jon Kamp, Aparajita Saha-Bubna, Jacob Bunge and Joseph Checkler

contributed to this report.)

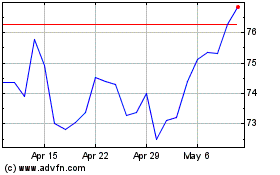

State Street (NYSE:STT)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jun 2024 to Jul 2024

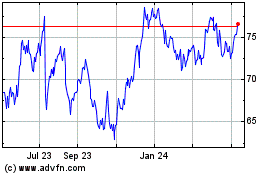

State Street (NYSE:STT)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jul 2023 to Jul 2024