By Andrew Beaton

In 2017, an attorney named Thomas Mars was driving around

Mississippi listening to an audiobook called "The System: The Glory

and Scandal of Big-Time College Football." He knew almost nothing

about college football. He knew even less about how much the book's

title would soon come to define him.

Three years later, Mars has become the unlikeliest rabble-rouser

in the sport. One of the few guys in the South who never bothered

to watch college football on weekends has developed a potent legal

practice helping players and needling the sport's most powerful

institutions.

Mars's work led to coach Hugh Freeze leaving Ole Miss amid an

embarrassing scandal. His assistance to players has made him the

only person beloved by fans at both Michigan and Ohio State. He's a

private sounding board for many of college football's most powerful

coaches and administrators -- the same people who one day could be

on the other side of one of his legal attacks.

In recent weeks, his cause célèbre was the Big Ten's decision to

postpone its football season because of the pandemic. Mars, 62

years old, represented the families of players who wanted to

reverse course -- which the conference did last week when it said

its season would begin in October. Mars exerted public pressure on

the Big Ten, and every one of its schools, by battling with the

universities' lawyers over records related to the decision while

privately helping players and coaches amplify the message that they

still wanted to play.

The oddest part is how Mars arrived at his role as college

football's chief antagonist. He was a cop. He was a young lawyer at

an Arkansas law firm working for a partner named Hillary Clinton.

He was director of the Arkansas State Police and a member of Mike

Huckabee's cabinet. He was Walmart Inc.'s general counsel and chief

administrative officer in the U.S.

"Nobody could've planned any of this," Mars said. "You couldn't

make this up or map it out."

Mars's mission to turn college football upside down began three

years ago when his cell phone buzzed as he pulled into the driveway

of his Arkansas home. It was his close friend and former pastor Rex

Horne, who wanted to know if Mars could help Houston Nutt, a

longtime coach at Arkansas and then at Mississippi. Nutt believed

Ole Miss was falsely attempting to pin its NCAA enforcement

problems on him. Nutt and Mars, it turned out, were once next-door

neighbors -- but Mars was the only guy on the block who never

bothered to introduce himself.

It wasn't the type of case Mars usually took on. He didn't know

the difference between a touchback and a safety. "I knew the object

was to get the football in the other guy's end zone," he says.

But he had already found that the best parts of his career came

from these unexpected twists. He was a middling college student who

became a police officer in Virginia before barely getting into

Arkansas's law school in 1982 as part of a dream to become an FBI

agent. He was ready to quit after a semester until the dean called

to tell him how dumb that would be: Mars was at the top of his

class.

That led to a clerkship in Utah on the Tenth Circuit Court of

Appeals in 1985, and just when he was about to finally get accepted

as an FBI agent he got a phone call that set him on a completely

different track. Hillary Clinton, a partner at the Rose Law Firm,

wanted to hire him. He reported directly to Clinton and Vince

Foster, with his tiny office serving as the unofficial waiting room

when Bill Cinton popped over from the governor's mansion.

Mars later set out on his own, and in the early '90s his first

major case was a successful class action in a natural gas deal

against a business that was co-owned by Jerry Jones. The Dallas

Cowboys owner was so impressed by the lawyer who whupped him in

court that he invited Mars onto the field for a game.

"I didn't like any part of that case, Tom, but you did a hell of

a job," he recalls Jones told him.

Mars's career took a new turn when he joined Wamart's legal team

in 2002, rising to become the retail giant's general counsel and

later its chief administrative officer in the U.S. But he left the

company after a 2012 scandal in which it was accused of paying

bribes around the world. Walmart paid $282 million in a settlement

with the U.S. government in which the company agreed it had lax

policies.

Mars felt the scandal was overblown and unfairly associated him

publicly with any wrongdoing. "It tarnished my reputation in a way

that I couldn't do anything about," he says. He adds he left

Walmart with a handsome severance -- and empathy for someone else

who was publicly accused of misdeeds he didn't have any part

in.

"I know what it's like to be in Houston Nutt's shoes," he

says.

Ole Miss' problems with Nutt could have disappeared with one

word: sorry.

Mars concluded that Ole Miss had engaged in a clear effort to

publicly blame its NCAA woes, which chiefly focused on

impermissible benefits involving boosters and recruits, on Nutt,

its former coach. Freeze, then the current coach, was a golden boy

in Oxford, Miss. who was beloved for both his piety and success,

including when he notably beat Alabama -- twice.

Mars asked for Ole Miss to privately apologize to Nutt, who was

distraught that his elderly mother had seen news reports alleging

he was behind the wrongdoing. The school refused. Mars went to

work.

"When you have Tom Mars on the other sideline, you better buckle

up," Nutt says.

As part of a defamation lawsuit against the school in July of

2017, Mars requested a trove of documents from Ole Miss under

public records law. He was looking for evidence of a specific phone

call Freeze made to a reporter, in which Freeze told the reporter

Nutt was behind the wrongdoing. Mars waged war with the school's

lawyers to obtain the records.

He got those records, and he found the smoking gun he needed:

evidence of that phone call. But the call logs contained something

even more troubling: Freeze had used his university phone to call

an escort service. Freeze was out of a job less than two weeks

after Nutt's lawsuit was filed. The Wall Street Journal later

reported the school had discovered a pattern of similar misconduct

when Freeze was traveling, using the school's plane, on recruiting

trips.

Freeze, now the coach at Liberty University, could not be

reached for comment on Mars through a school spokesman.

Mars was considered an enemy of state in Oxford, Miss. Nutt got

his apology a few months later. But when Mars returned to his law

practice, his life shifted unexpectedly again.

The parents of Ole Miss players, who weeks earlier loathed him

for tearing down the program, sought to hire him. The families felt

they had been falsely told when they were recruited that the

program's NCAA problems occurred under Nutt, not Freeze. They

wanted waivers from the NCAA to transfer and be immediately

eligible to play. It was Mars vs. Ole Miss Part II.

Those players included Shea Patterson, a highly-regarded

quarterback who left for Michigan and was granted immediate

eligibility against Ole Miss' wishes. It was such a celebrated

moment in Ann Arbor that Mars won't have to pay for his own beer at

Rick's ever again.

Yet he's just as highly regarded by Ohio State fans. As word

spread, dozens of athletes across the country started working with

Mars. He was retained by the family of Justin Fields, who was

seeking to transfer from Georgia. Fields is now the Buckeyes' star

quarterback.

Mars charges the families a heavily-discounted rate because he

can afford thanks to his severance package from Walmart, he

says.

Which is also why, now, he's happy to be working -- and getting

public notice -- for something he finds personal satisfaction in.

His success representing transfers led parents to seek him out when

the Big Ten season had been postponed. The parents and players

wanted an explanation for why the conference pumped the brakes

while others went forward. Mars became their public advocate,

questioning the legality behind the decision making and requesting

internal records over the decision.

"I only resort to being combative and increasingly combative if

necessary," Mars says.

Write to Andrew Beaton at andrew.beaton@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 21, 2020 09:38 ET (13:38 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

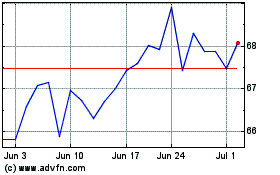

Walmart (NYSE:WMT)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

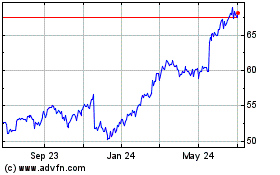

Walmart (NYSE:WMT)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024