By Sarah Krouse

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (February 4, 2020).

Bernard Ebbers, the former WorldCom Inc. chief executive who

spent more than 13 years in prison for participating in one of the

largest accounting frauds in U.S. history, died Sunday at age 78,

according to his family.

In December, Mr. Ebbers was granted early release from prison

because of his deteriorating health.

In a statement sent by an attorney confirming Mr. Ebbers's

death, his family again defended his early release, saying keeping

him in prison, "especially in his unexplained and undiagnosed

deteriorated condition, would not bring back anyone's

investments."

Mr. Ebbers, who built WorldCom from scratch through dozens of

takeovers, was once dubbed the "telecom cowboy" for his purchase of

larger rival MCI Communications Corp. At its peak in 1999, WorldCom

had a market capitalization of about $180 billion. Within a few

years of that peak, the fraud came to light, and the company

collapsed into bankruptcy.

The ex-CEO was found guilty in 2005 on nine counts including

securities fraud and conspiracy to commit fraud by falsifying

WorldCom's financial results, and received a 25-year sentence. He

and other executives improperly boosted profit by booking operating

expenses as capital spending, which can be deducted from earnings

in small chunks over time.

The telecom giant was forced to restate its earnings after an

internal auditor exposed the fraud to regulators; the company filed

for bankruptcy protection in 2002 and laid off thousands of

employees. With assets valued at $107 billion, it was at the time

the largest bankruptcy filing in U.S. corporate history.

Mr. Ebbers's conduct "caused literally tens of thousands or more

of innocent shareholders to suffer billions of dollars in losses,"

federal prosecutor David Anders wrote in a sentencing memo to the

judge during the trial.

Known for his white hair, blue eyes and penchant for cowboy

boots and turquoise jewelry, Mr. Ebbers had pleaded not guilty to

the charges. He claimed he didn't know the company's finances were

being manipulated.

Born on Aug. 27, 1941 in Edmonton, Alberta, to a deeply

religious family, Mr. Ebbers was the second of five children. His

father, John T. Ebbers, worked as a traveling salesman and

mechanic.

"Bernie" Ebbers was raised in Edmonton until his family moved to

California in the late 1940s. They later relocated to Gallup, N.M.,

and Mr. Ebbers attended a boarding school on a Navajo

reservation.

He attended and left two colleges before returning to Edmonton.

He delivered milk and worked as a bouncer at a nightclub,

eventually enrolling at Mississippi College, a private Baptist

college in the Deep South.

He played college basketball and secured a scholarship. After an

injury stopped him from playing, Mr. Ebbers coached basketball and

continued to do so after he graduated in 1967.

Mr. Ebbers married Linda Pigott, his first wife, in 1968, and

they had four daughters, Treasure, Ave, Joy and Faith. Mr. Ebbers

and his wife divorced in 1997, and he remarried two years

later.

Early in his professional life Mr. Ebbers worked in a garment

factory in Brookhaven, Miss., and later began assembling a

portfolio of motels. He bought his first motel in Columbia, Miss.,

in 1974, moving with his then-wife into a two-bedroom trailer in

the property's parking lot.

The telecommunications industry, which had long been controlled

by a monopoly known as Ma Bell, was on the cusp of a change that

would redefine the companies that dominated it. A judge in 1983

ordered the breakup of AT&T's Bell System, which spurred some

investors and entrepreneurs to seek profits from reselling

long-distance service.

Mr. Ebbers and a handful of investors backed a company called

Long Distance Discount Service, or LDDS. Mr. Ebbers became chief

executive of the money-losing company in 1985 and helped it gain

scale through rapid acquisitions.

He often took on debt to complete those purchases. As the

company grew and his personal wealth accumulated, Mr. Ebbers would

use increasingly burdensome debt to fuel acquisitions.

The company was renamed WorldCom in 1995. He led the company

through dozens of deals, some worth billions of dollars, while

continuing to invest in a personal real-estate collection.

Properties he owned included a sprawling ranch in British

Columbia, a timberland tract and shipyard in Savannah, Ga., and a

large home in Brookhaven, Miss.

Mr. Ebbers began to borrow money from WorldCom in the late

1990s, using the loan in part to buy more company stock.

Meanwhile, his deal ambitions grew. WorldCom in 1998 bought MCI,

the No. 2 long-distance provider, for $37 billion, and put Mr.

Ebbers at the helm of the combined company. The following year, he

tried an even bigger deal, making a $115 billion bid for Sprint,

the No. 3 long-distance provider and a wireless carrier. The deal

was called off in 2000 after U.S. and European regulators moved to

block it.

He earned a reputation as a competitive and hard-driving boss

who expected loyalty and had an appetite for risky bets in the name

of growth. In a book on WorldCom's rise and fall, reporter Lynn W.

Jeter wrote Mr. Ebbers carefully monitored which shareholders and

employees sold stock. His staff tried to avoid being on "Bernie's

List," she wrote.

WorldCom began to show signs of stress in 2000 when its share

price declined as the dot-com stock market bubble popped, leading

to a shakeout of internet and telecom companies. At the time, the

company guaranteed and then assumed Mr. Ebbers's borrowings.

He was fired as CEO in April 2002 partly because he owed

WorldCom more than $400 million, including money the company lent

him to cover margin calls on loans secured by company stock. The

scale of what Mr. Ebbers had borrowed from the company helped spur

a Securities and Exchange Commission inquiry.

By early summer that year, an internal auditor conducting a

review at the direction of the company's new chief executive

spotted accounting irregularities, beginning to unearth the scale

of the fraud that had been committed.

Mr. Ebbers appeared at his Mississippi church in 2002 after he

was ousted to attend that day's service and to teach Sunday school.

At the end of the service he walked to the front of the church and

spoke to the parish: "I just want you to know you aren't going to

church with a crook."

He wasn't the only executive punished for the accounting fraud,

but he did face the longest sentence.

WorldCom's former chief financial officer, Scott Sullivan, who

engineered the fraud and worked closely with Mr. Ebbers, was

sentenced to five years in prison after cooperating with

prosecutors. His testimony that Mr. Ebbers knew of the accounting

methods used was key to the prosecution's case. Mr. Ebbers took the

stand and tried to distance himself from Mr. Sullivan during the

trial.

Friends, former colleagues, family and at least one former

fellow church member wrote to the court on behalf of Mr. Ebbers,

vouching for his character. His lead defense attorney said his

client had given more than $100 million to charities anonymously.

Mr. Ebbers also said he suffered from a heart condition called

cardiomyopathy, in which the heart muscle doesn't pump blood

properly.

The former chief executive hung his head as a judge delivered

his sentence in 2005 and cried while hugging his then-wife, Kristie

Ebbers. He drove himself to prison in a Mercedes the following year

and spent part of his sentence as inmate No. 56022-054 in a

low-security prison in Louisiana. He was later transferred to FMC

Fort Worth, a federal prison hospital in Texas with round-the-clock

nursing care.

To settle a class-action lawsuit brought by WorldCom

shareholders, Mr. Ebbers agreed to pay $5 million cash and transfer

nearly all of his assets, including his home and interests in

timberland, a trucking company, marina, golf course, hotel and

other real-estate ventures.

His second wife filed for divorce in 2008, two years after his

prison sentence began.

While Mr. Ebbers was standing trial, WorldCom, which re-emerged

from bankruptcy as MCI Inc. in 2004, agreed to be acquired by

Verizon Communications Inc. The $8.5 billion deal closed in early

2006.

More than 13 years into his sentence, Mr. Ebbers was granted

compassionate release from prison, citing "extraordinary and

compelling medical circumstances" that arose during the time he

served. Judge Valerie Caproni granted his family's request for a

compassionate release in December.

His daughter, Joy Ebbers Bourne, told the court that she visited

and spoke with her father regularly and had noticed his health

decline.

Mr. Ebbers had lost weight, had difficulty walking and struggled

to sleep, she wrote in court documents. He also had macular

degeneration, an eye disease that made him legally blind, in

addition to cardiomyopathy, which puts him at risk of a heart

attack or stroke, she wrote.

The former executive used a magnifying glass to read, fill out

medical forms and make phone calls in prison because of his failing

eyesight, she wrote, and wasn't permitted to replace it when it

broke. He was assaulted in 2017 by a fellow prisoner after he

unintentionally bumped into the person because of his eyesight

problems, she added.

Mr. Ebbers's scheduled release date had been July 4, 2028,

according to the Federal Bureau of Prisons.

When Judge Barbara Jones sentenced Mr. Ebbers to 25 years in

prison in 2005, she acknowledged that it was likely a life

sentence. That judge, however, later wrote two letters on Mr.

Ebbers's behalf.

She wrote to President Trump in 2017 supporting Mr. Ebbers's

then-petition to have his sentence commuted, and another in

September to a district court judge in New York that said he has

been punished enough.

In her most recent letter she said reducing the sentence in

light of his medical conditions "would not diminish the message

that I sought to convey in 2005. It would show compassion."

Mr. Ebbers's family said in the statement that after grieving

they plan to advocate for compassionate release for other

prisoners.

Write to Sarah Krouse at sarah.krouse@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 04, 2020 02:47 ET (07:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

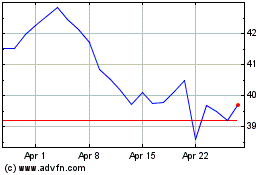

Verizon Communications (NYSE:VZ)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

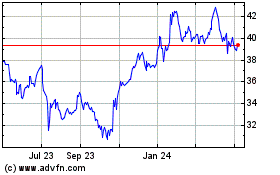

Verizon Communications (NYSE:VZ)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024