The Glut Drowning the Oil Market

May 07 2020 - 5:59AM

Dow Jones News

By Amrith Ramkumar, Tristan Wyatt and Collin Eaton

The world is awash in oil.

Lockdown measures are crippling demand, and supply isn't falling

quickly enough to keep up. Oil-storage tanks around the world are

rapidly filling with crude, leaving the new production coming out

of the ground with nowhere to go.

The overwhelming glut is threatening one of the world's vital

industries and could prolong the economic fallout from the

coronavirus. As storage filled, one price for U.S. crude recently

fell below $0 a barrel -- a first in oil-market history --

effectively meaning sellers would have to pay buyers to take

barrels off their hands.

Even with a recent rebound as parts of the world reopen for

business, oil trades at a fraction of where it started the year.

Most energy companies would lose money producing at these

levels.

Stockpile data are incomplete or delayed, but recent figures

already illustrate the crisis:

Global oil inventories fall into two main categories: commercial

stockpiles and strategic reserves held for emergencies. Most

investors focus on changes in commercial inventories because those

are most sensitive to shifts in global supply and demand.

Producers and traders who don't want to sell crude at today's

low prices can try to store it in hubs around the world, then sell

in the future. The problem now is that demand for storage space is

skyrocketing.

U.S. commercial stockpiles are rising at their quickest pace

ever in government data going back to 1982. At 532.2 million

barrels during the week ended May 1, inventories are soon expected

to blow past a record of 535.5 million barrels from March 2017.

The increase has been pronounced in Cushing, Okla., a key hub.

Analysts said dwindling storage space in Cushing contributed to the

recent drop in one futures contract below $0 a barrel. On April 20,

that futures contract was close to its expiration date -- meaning

traders had to either sell it or accept delivery of actual barrels

of oil at Cushing by the following month.

Those stuck holding the contracts likely couldn't find available

storage for oil and began paying others to take the contracts from

them.

It is hard to know how much space is actually available.

Logistical hurdles mean storage tanks can't be filled to the brim,

and competition for remaining space is fierce. That means much of

the remaining empty room could have already been claimed for future

use. Even so, the official Energy Information Administration

figures show Cushing inventories rising at a pace that would have

them completely full in weeks.

As a result, crude-futures prices recently traded around their

lowest levels in two decades.

Normally, when oil prices slide, consumers travel more, limiting

the price drop and eventually spurring a rebound. But with much of

the world practicing social distancing, fuel consumption has

plummeted.

That means companies industrywide are struggling. Refiners such

as Marathon Petroleum Corp. and Valero Energy Corp. that take in

oil and turn it into petroleum products including gasoline are

bringing in much less crude. The extra crude must find a home in

storage.

In addition to Cushing, other U.S. storage hubs are located in

the Gulf Coast. A flood of oil from Saudi Arabia, the world's

largest exporter, is starting to arrive in the region -- fallout

from a March production feud between the kingdom and Russia that

raised global supplies even as demand crashed.

That extra crude could make the glut in the U.S. even worse. Oil

normally moves seamlessly through a network of pipelines and

storage hubs across the country, but more of it will have nowhere

to go.

The excess oil is forcing energy companies to curb spending and

shut in productive wells. Some companies are starting to go

bankrupt and lay off employees. The turmoil is erasing hundreds of

billions of dollars from the sector's market value.

There is also a large amount of oil floating at sea with nowhere

to go, according to cargo tracker Kpler. Some ships have even been

crowding off the California coast recently.

Oil-market analysts are also watching inventories overseas,

particularly in China, the world's largest commodity consumer.

Figures from analytics company Kayrros show a rise in those

stockpiles recently, too.

And with supply projected to continue exceeding demand for the

time being, many analysts expect prices to remain volatile.

--Emil Lendof and Sarah Toy contributed to this article.

Write to Amrith Ramkumar at amrith.ramkumar@wsj.com and Collin

Eaton at collin.eaton@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 07, 2020 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

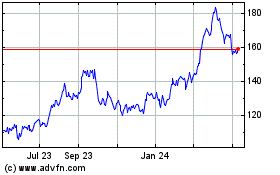

Valero Energy (NYSE:VLO)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

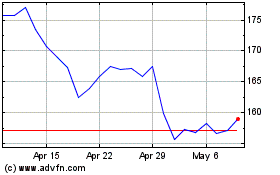

Valero Energy (NYSE:VLO)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024