By Robert McMillan and Dustin Volz

Investigators probing a massive hack of the U.S. government and

businesses say they have found concrete evidence the suspected

Russian espionage operation went far beyond the compromise of the

small software vendor publicly linked to the attack.

Close to a third of the victims didn't run the SolarWinds Corp.

software initially considered the main avenue of attack for the

hackers, according to investigators and the government agency

digging into the incident. The revelation is fueling concern that

the episode exploited vulnerabilities in business software used

daily by millions.

Hackers linked to the attack have broken into these systems by

exploiting known bugs in software products, by guessing online

passwords and by capitalizing on a variety of issues in the way

Microsoft Corp.'s cloud-based software is configured, investigators

said.

Approximately 30% of both the private-sector and government

victims linked to the campaign had no direct connection to

SolarWinds, Brandon Wales, acting director of the Cybersecurity and

Infrastructure Security Agency, said in an interview.

The attackers "gained access to their targets in a variety of

ways. This adversary has been creative," said Mr. Wales, whose

agency, part of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, is

coordinating the government response. "It is absolutely correct

that this campaign should not be thought of as the SolarWinds

campaign."

Corporate investigators are reaching the same conclusion. Last

week, computer security company Malwarebytes Inc. said that a

number of its Microsoft cloud email accounts were compromised by

the same attackers who targeted SolarWinds, using what Malwarebytes

called "another intrusion vector." The hackers broke into a

Malwarebytes Microsoft Office 365 account and took advantage of a

loophole in the software's configuration to gain access to a larger

number of email accounts, Malwarebytes said. The company said it

doesn't use SolarWinds software.

The incident demonstrated how sophisticated attackers could

leapfrog from one cloud-computing account to another by taking

advantage of little-known idiosyncrasies in the ways that software

authenticates itself on the Microsoft service, investigators said.

In many of the break-ins, the SolarWinds hackers took advantage of

known Microsoft configuration issues to trick systems into giving

them access to emails and documents stored on the cloud.

SolarWinds itself is probing whether Microsoft's cloud was the

hackers' initial entry point into its network, according to a

person familiar with the SolarWinds investigation, who said it is

one of several theories being pursued.

"We continue to collaborate closely with federal law enforcement

and intelligence agencies to investigate the full scope of this

unprecedented attack," a SolarWinds spokesman said in an email.

"This is certainly one of the most sophisticated actors that we

have ever tracked in terms of their approach, their discipline and

range of techniques that they have," said John Lambert, the manager

of Microsoft's Threat Intelligence Center.

In December, Microsoft said that the hackers who targeted

SolarWinds had accessed its own corporate network and viewed

internal software source code -- a lapse of security but not a

catastrophic breach, according to security experts. At the time,

Microsoft said it had "found no indications that our systems were

used to attack others."

The hack will take months or more to fully unravel and is

raising questions about the trust that many companies put in their

technology partners. The U.S. government has publicly blamed

Russia, which has denied responsibility.

The data breach has also undermined some of the pillars of

modern corporate computing, in which companies and government

offices entrust myriad software vendors to run programs remotely in

the cloud or to access their own networks to provide updates that

enhance performance and security.

Now corporations and government agencies are grappling with the

question of how much they can truly trust the people who build the

software they use.

"Malwarebytes relies on 100 software suppliers," said Marcin

Kleczynski, the security company's chief executive. "How do I know

that Zoom or Slack isn't next and what do I do? Do we start

building software in-house?"

The attack surfaced in December, when security experts

discovered hackers inserted a backdoor into updates to SolarWinds'

software, called Orion, which was used widely across the federal

government and by a swath of Fortune 500 companies. The scope and

sophistication of the attack surprised investigators almost the

moment they began their probe.

SolarWinds has said that it traced activity from the hackers

back to at least September 2019, and that the attack gave the

intruders a digital back door into as many as 18,000 SolarWinds

customers.

Mr. Wales of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security

Agency said some victims were compromised before SolarWinds

deployed the corrupted Orion software about a year ago.

The departments of Treasury, Justice, Commerce, State, Homeland

Security, Labor and Energy all suffered breaches. In some cases

hackers accessed the emails of those in senior ranks, officials

have said. So far, dozens of private-sector institutions have also

been identified as compromised in the attack, Mr. Wales said,

adding that the total is well under 100.

Investigators have tracked the SolarWinds activity by

identifying the tools, online resources and techniques used by the

hackers. Some U.S. intelligence analysts have concluded that the

group is tied to Russia's foreign intelligence service, the

SVR.

Mr. Wales said his agency isn't aware of cloud software other

than Microsoft's targeted in the attack. And investigators haven't

identified another technology company whose products were broadly

compromised to infect other organizations the way SolarWinds was,

he said.

The effort to target Microsoft's cloud software shows the

breadth of hackers' efforts to steal sensitive data. Microsoft is

the world's largest business software provider, and its systems are

widely used by corporations and government agencies.

"There are lots and lots of different ways into the cloud," said

Dmitri Alperovitch, executive chairman of the Silverado Policy

Accelerator, a cybersecurity think tank. Because so many companies

have moved to the Microsoft 365 cloud in recent years, it "is now

one of the top targets," he said.

Another security company that doesn't use the SolarWinds

software, CrowdStrike Inc., said the same attackers unsuccessfully

tried to read its email by taking control of an account used by a

Microsoft reseller that it worked with. The hackers then attempted

to use that account to access CrowdStrike's email.

In December, Microsoft notified both CrowdStrike and

Malwarebytes that the SolarWinds hackers had targeted them.

Microsoft said then that it had identified more than 40 customers

hit by the attack. That number has since increased, said a person

familiar with Microsoft's thinking.

When the SolarWinds hack was first uncovered, current and former

national security officials quickly concluded it was one of the

worst breaches on record -- an intelligence coup that went

undetected for several months or longer that allowed suspected

Russian spies access to internal emails and other files in several

government agencies.

As investigators have learned more about the scope of the hack

and its reach beyond SolarWinds, officials and lawmakers have begun

to speak about it in even more dire terms. Last week, President Joe

Biden instructed his director of national intelligence, Avril

Haines, to conduct a review of Russian aggression against the U.S.,

including the SolarWinds hack.

"This is the greatest cyber intrusion, perhaps, in the history

of the world," Sen. Jack Reed, a Democrat, said earlier this month

during a confirmation hearing for Ms. Haines.

Mr. Wales said that the hacking operation was "substantially

more significant" than a previous hacking spree against cloud

providers, known as Cloud Hopper and linked to the Chinese

government, widely considered to be one of the largest-ever

corporate espionage efforts. The hackers in this campaign have been

able to compromise core infrastructure of government and private

sector victims in a way that dwarfs that attack, Mr. Wales

said.

Investigators still believe the primary purpose of the hacking

campaign, which the government has said is ongoing, is to glean

information by spying on federal agencies and high-value corporate

networks -- or compromise other technology companies whose access

could lead to follow-on attacks.

"We continue to maintain that this is an espionage campaign

designed for long-term intelligence collection," Mr. Wales said.

"That said, when you compromise an agency's authentication

infrastructure, there is a lot of damage you could do."

-- For more WSJ Technology analysis, reviews, advice and

headlines, sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Write to Robert McMillan at Robert.Mcmillan@wsj.com and Dustin

Volz at dustin.volz@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

January 29, 2021 07:14 ET (12:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2021 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

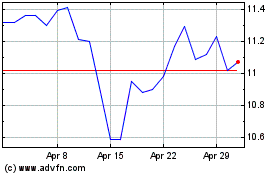

SolarWinds (NYSE:SWI)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

SolarWinds (NYSE:SWI)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024