By Jason Zweig

Morgan Stanley's takeover of E*Trade Financial Corp. for $13

billion shows how drastically the brokerage industry's business

model has changed.

Firms no longer want to offer investment products from all

sources. Instead, they want to milk their customers' cash and

manage all the assets themselves. Investors need to understand the

rules of the new game.

For decades, big banks and brokers aspired to become " financial

supermarkets" where consumers could open bank accounts and buy

stocks and bonds, mutual funds, insurance and the like.

In the 1980s, Prudential Financial Inc. sold securities

alongside insurance. American Express Co. pushed brokerage services

and financial advice to credit-card customers. In the 1990s,

Citigroup Inc. flogged stocks and mutual funds in its bank

branches. Even the retailer then known as Sears, Roebuck & Co.

sold securities in its department stores, earning the nickname

"Socks 'n' Stocks."

Some outfits -- especially Charles Schwab Corp. and Fidelity

Investments -- made one-stop-shopping work, managing money

themselves while offering funds from other firms as well.

But most flailed. Prudential paid more than $1.5 billion in

regulatory fines over sales of risky partnerships. American

Express, Citigroup and Sears sold their brokerage and fund

units.

Nowadays, the name of the game isn't to offer all things from

all sources to all investors. It's to offer only what keeps the

fees in-house.

Much as the Plains Indians used every part of the buffalo, from

flesh to skin to horn to sinew and hooves, Wall Street excels at

creating strategies with fees that can be harvested from every

component. In practice, that means investment firms want to grab as

much of your money as they can and farm out as little of it as

possible.

Wall Street can't make oodles of money off your trades anymore;

technology has driven commissions to near zero. And it can't make

the windfall it once did off managing portfolios; there, too,

market-tracking index funds and exchange-traded funds have become

cheap as dirt.

Where are the remaining profits for brokerage firms?

They can take your cash and, instead of investing it for your

benefit in the highest-yielding money fund or deposit account, they

can put it in their own bank and pay you peanuts. Then they lend it

out and keep the profit for themselves.

Morgan Stanley, E*Trade and Schwab all own banks to which they

route much of their customers' cash. E*Trade pays its customers

0.01% to 0.25% on their uninvested cash; Morgan Stanley, 0.03% to

0.2%; Schwab, 0.06% to 0.3%.

Brokerages have been pocketing 2% and up on that money (and you

can do almost as well, if you pull the cash from your brokerage

account and park it in a certificate of deposit or savings account

at the right online bank).

Schwab, which has hoovered up $220 billion in bank deposits,

earned 61% of its total net revenues in 2019 from the interest it

captured on those balances.

Financial firms can also invest your money in funds they run

themselves. That way, they capture fees you would otherwise pay to

somebody else.

By my estimate, 57% of the $16.5 billion in total assets of the

FlexShares ETFs, managed by an affiliate of Northern Trust Corp.,

are held by Northern Trust clients. The firm "adheres to an

open-architecture investment platform, applying the same objective

and rigorous selection process to third-party and proprietary

investment products," says a spokesman.

Even Vanguard Group, the investment giant owned by its fund

shareholders, is freezing out other firms. In its $161 billion

Personal Advisor Services program, which manages money for

individual clients, Vanguard won't recommend mutual funds or ETFs

from any other companies. Clients aren't compelled to sell their

non-Vanguard investments, says a company spokesman.

The house brand isn't always bad, of course. A firm's own funds

can be cheaper or better than the alternatives. But investors need

to be on their guard: Under federal rules, a firm can recommend its

store-brand investments whether they are ideal or not, so long as

they are a "reasonable" choice.

Finally, complexity pays -- for investment firms, if not their

clients. Take " structured notes." The return on these short-term

debt instruments is pegged -- often in complex ways -- to the

performance of other assets, often stocks or market indexes.

You can lose money, but issuance is booming; in less than one

hour on Thursday, banks and brokers filed nine prospectuses with

the Securities and Exchange Commission. Here again, firms often

hawk them to their own clients.

Structured notes are a fee bonanza. Firms rake in upfront

charges of 1% to 4.5%. They earn more fees for calculating the

value of the notes. They also can make money by trading against the

assets the structured products are linked to. There's generally no

market, so if you need to sell before maturity, the firm will buy

your note at a price it sets -- including a "spread," or trading

cost to you.

The best questions to ask on the new Wall Street, then, are

these. What are my financial advisers doing in-house that someone

elsewhere could do cheaper or more safely? Where do my brokers put

their own cash? Do my advisers buy structured products for

themselves? Above all, should I diversify not just my portfolio --

but my financial advice?

Write to Jason Zweig at intelligentinvestor@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 21, 2020 11:14 ET (16:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

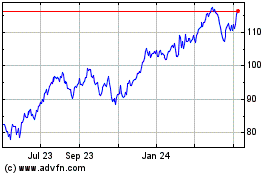

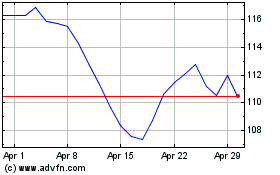

Prudential Financial (NYSE:PRU)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Prudential Financial (NYSE:PRU)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024