By Alistair MacDonald

Gold miners are riding high as the metal trades at record

prices, but digging it out of the ground is getting harder.

Gold is among the rarest metals in the earth's crust and much of

the easier-to-get ore has already been mined. What is left is

harder to find and more expensive to extract, miners say.

While that isn't an immediate worry, with gold prices hitting

$2,000 an ounce for the first time this month, miners face the

longer-term prospect of higher costs and drilling in less

hospitable places. A sharp selloff in gold this week also reminded

companies that high prices can't be taken for granted.

Gold prices are up around 28% this year. Miners have used the

rally to pay down debt and increase dividends, rather than start

new projects, with executives wary of repeating their costly

overexpansion during the last big run-up in prices.

"We are definitely past peak gold," said Mark Bristow, chief

executive of Barrick Gold Corp., the world's second-largest gold

miner by market capitalization. He estimates that the new metal

added to miners' reserves since 2000 replaces only half of the gold

they mined in that period.

Miners are spending less money on finding new gold, with the

industry's exploration budget at $4.44 billion last year, 63% lower

than its record high in 2012, according to Australia-based Minex

Consulting.

That comes as finding new gold is becoming more expensive as

miners have to dig deeper and enter more remote terrain in search

of untapped deposits. The average cost to find an ounce of gold was

$62 between 2009 and 2018, more than double the cost for the

previous decade, according to Minex.

"What new fresh discoveries have been made? Not a lot," said

Sean Boyd, the chief executive of Agnico Eagle Mines Ltd, a

Canada-based mining company that has turned to the Arctic to find

higher quality deposits. "If they have, they've been found in tough

parts of the world," he said.

The grade of gold being mined -- the amount of metal for every

ton of rock mined -- is also getting worse. The average mine grade

has fallen from over 10 grams a ton in the early 1970s to around

1.46 grams a ton last year, according to Metals Focus, a

precious-metals consulting firm.

Lower grades of gold require digging up more earth to find the

metal so are more expensive per ounce to mine. In 1990, the cost of

mining an average ounce of gold, calculated by looking at the total

cash costs plus capital expenditure, was $253, according to

Refinitiv. Last year it was $705.

The fundamental problem for gold miners is that there simply

isn't that much to unearth. All the gold ever mined can fit into a

69-foot cube, according to the World Gold Council. At around 0.005

parts per million, gold's presence in the Earth's crust is tiny

compared with that copper, at over 50 parts, or iron, at more than

50,000.

Some miners and geologists argue the metal is nowhere near to

running out as a minable commodity. Gold may be harder to mine, but

technology can bring costs down and allow access to new

mineral-rich places, such as the ocean floor, they say.

"We say we are running out, but we are not really looking," said

Ferri Hassani, a professor at the Department of Mining and

Materials Engineering at Canada's McGill University. Mr. Hassani

said, for instance, that nobody thought there would be gold in

Iran, but geologists are finding it there.

People have talked of mining the ocean floor since the 1870s,

when a British Navy research vessel charted nodules containing

metal deposits throughout the seas. Aside from diamonds relatively

close to the shore, oceans remain untapped, while most miners

aren't keen on digging in politically risky places like Iran.

Lower gold supplies won't necessarily make the metal more

expensive for buyers. Supply doesn't affect gold prices in the way

it does other commodities, given the metal's status as a financial

asset as much as a material for use.

The recent rally was driven by investors seeking havens amid the

coronavirus pandemic and persistently low, and in some cases

negative, interest rates. Gold is less attractive against other

safe-haven assets, like U.S. Treasurys, when rates are high.

Also, unlike many other commodities, like oil, the supply of

this virtually indestructible metal doesn't disappear.

Meanwhile, gold miners are enjoying the bounty of higher prices

when Covid-19 has disrupted production and increased costs. Share

prices have jumped, with Barrick Gold and Newmont Corp. both up

around 47% this year and Kinross Gold Corp. 88% higher.

Gold companies are doling out dividends. Barrick Gold announced

an increase of 14% for its second-quarter payout, while Newmont has

increased its dividend by 79%.

South Africa's Gold Fields Ltd. said it would capitalize on the

high gold price by paying down around $750 million in debt by the

end of the year.

Still, miners say they aren't ramping up production, which has

gradually increased over the last decade to 108 million ounces last

year, according to Refinitiv.

Barrick, Newmont, Agnico Eagle and others say they will only

approve new projects if they can make money with gold at $1,200,

about 40% below where the metal is trading. During the last gold

price bull run, which peaked in the fall of 2011, miners increased

their reserves, started expensive new projects and went on

acquisition sprees, much of which turned sour as the price fell 43%

in the following four years.

"Everyone kept changing their cut off grade and following the

gold price, " said Barrick's Mr. Bristow.

This time, said Agnico Eagle's Mr. Boyd, "The key will be to

show that industry has not lost its discipline."

Write to Alistair MacDonald at alistair.macdonald@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

August 16, 2020 08:14 ET (12:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

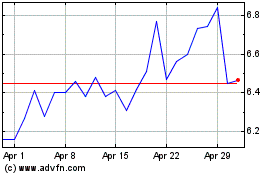

Kinross Gold (NYSE:KGC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

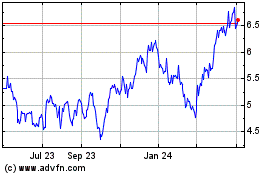

Kinross Gold (NYSE:KGC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024