By John D. Stoll

The United Auto Workers spent the 1980s primarily worried about

job security. As Japanese car companies stole Detroit's market

share and robots invaded auto plants, union bosses anticipated less

for their army of workers to do.

They convinced General Motors Co. and its rivals to form what

was called a Jobs Bank that kept paying employees even if their

positions were eliminated by automation or market shifts.

When GM filed for bankruptcy protection two decades later, the

Jobs Bank was held up as an example of the gaggle of gold-plated

benefits the UAW amassed in contract negotiation upon contract

negotiation. Needing a government bailout in 2009 to get the

General back on its feet, union officials gave up many of those

perks. Executives vowed to never give them back.

If this autumn's long UAW strike teaches us anything, it's that

GM has a long memory. Its new generation of leaders doesn't want to

return to the old days. The company is pouring billions into

electric cars and autonomous vehicles, and needs maximum

flexibility to minimize the risk.

Fighting the UAW has proven tough. The union is more concerned

with shoring up its dwindling ranks than doing GM a favor.

Automobile design is headed for big changes, and a preference for

shipping production out of the country threatens its ranks.

Electric vehicles, which are less complex than gasoline

counterparts, are expected to require 30% fewer workers -- bad news

for a union that now only represents about 150,000 people at Big

Three auto plants -- a minority of American auto workers. The

industry's most profitable vehicles, meanwhile, are increasingly

coming from Mexico.

This new GM doesn't want to take financial responsibility for

the changes electric cars will bring. Want proof? A negotiation

that should have taken at most a couple of weeks of talks to

resolve blew up into a 40-day strike, costing GM about $3 billion

in lost production and costing UAW members $8,700 per worker in

lost compensation. This would be a lot for Chief Executive Mary

Barra to lose over a routine contract negotiation.

Had the bargaining just been about pay raises, monthly

health-care costs or bonuses, a deal would have been struck with

far less bloodshed, people involved in the talks say. The new

contract costs GM $350 million in additional annual labor costs, or

52% more than the roughly $230 million increase executives have

been targeting. These numbers are rounding errors for a company

earning $150 billion annually, and it doesn't take a protracted

strike to get on the same page. ( Ford Motor Co. agreed to terms

with the UAW after a week of formal talks).

But because the UAW came into GM negotiations looking to win

back certain items it gave up during the financial crisis, the auto

giant dug in, these people say. The union wanted an increase in

defined-benefit payments for the large portion of employees still

eligible for pensions; it wanted additional payments to retirees;

and it wanted more say in where GM builds its products.

"What GM was saying is, 'We can afford the new economics of a

labor deal, but we cannot afford to go bankrupt again,'" said Colin

Lightbody, a longtime contract bargainer for Chrysler who is now a

consultant. "That became the underlying agenda in these

negotiations and sent a message in these negotiations that 'we're

sticking to our guns on that.'"

Art Schwartz, a former GM labor negotiator and president of the

consulting firm Labor and Economics Associates, told me this week

the auto maker succeeded in "retaining the right to run the

company." He pointed to Paragraph Eight in the hulking GM-UAW

contract, which says the union's job is to negotiate -- everything

else is up to the company.

This is an important message not only to the union, but also to

Washington. Bloomberg recently reported the White House wants to

control where cars are made. This is a recipe for disaster in a

capital-intensive and cyclical business where flexibility is

king.

"We have maintained our ability to adjust our workforce in

response to changing industry levels," GM's Chief Financial Officer

Dhivya Suryadevarea said in a call with analysts this week.

GM isn't alone in needing wiggle room. Fiat Chrysler Automobiles

NV is planning to merge with French auto maker PSA Group, the maker

of Peugeot. This will increase Chrysler's exposure to the European

market, which is saddled with excess production capacity and known

for giving an upper hand to labor unions in protecting unprofitable

jobs. Strong American assembly plants are core to case Chrysler has

made to PSA for the merger.

Anyone questioning whether GM and its rivals still need this

flexibility should study a spreadsheet that details what's called

the factory-utilization rate. Long an indicator of a company's

underlying health, it measures the percentage of a plant's capacity

to churn out cars used during a 16-hour workday. Auto executives

hate it when the lights are off on a plant. Every minute of those

16 hours that the assembly line isn't running represents piles of

wasted cash.

GM, flush with U.S. factories even after its bankruptcy, is

responsible for about one-third of the American auto industry's

unused production capacity, according to the Center for Automotive

Research. That's a disproportionate burden for a company with just

17% market share.

That's why the company announced a plan last year to close

several factories, including a facility in Lordstown, Ohio, and

stuck to that plan even as President Trump, several lawmakers and

union leaders criticized the move. The data indicate more pain on

the horizon.

GM builds the electric Chevy Bolt and small cars, for instance,

at a factory in Orion Township, Mich., that it was forced to keep

open indefinitely under the terms of its bailout from the Treasury

Department. The sprawling facility north of Detroit employs about

750 people and is capable of building tens of thousands of cars a

month. It currently builds 170 a day, or less than 10% of what it

is capable of building during a two-shift workday, according to

Wards Intelligence.

The industry average for capacity utilization? Roughly 88%,

Wards says.

GM is keeping Orion open because it sees the factory as a test

bed for electric vehicles, which currently are money losers because

of the high cost of batteries. Another EV is slated to be added to

that assembly line during the next contract.

The company is also committing to keep open another factory near

Detroit it had previously planned to close. The good news for

workers at that plant is that the new product will be a pickup

truck, competing in the hottest segment in America. The risky part:

The truck will be electric.

But these cars and trucks represent more of a half-court shot

than a slam dunk, and GM has shown willingness in recent years to

cut losses when projects go from dream to headache.

The latest contract insures GM can quit banging its head against

the wall anytime it wants.

Write to John D. Stoll at john.stoll@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

November 01, 2019 13:10 ET (17:10 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

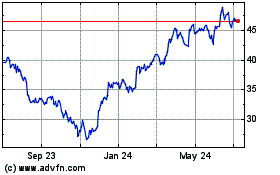

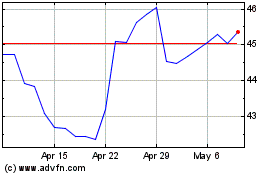

General Motors (NYSE:GM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

General Motors (NYSE:GM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024