By Jean Eaglesham and AnnaMaria Andriotis

Early this year, Phoebe Tu was rejected for a $30,000 loan to

consolidate her credit-card debt. Within days, the gears were

turning in a multibillion-dollar lending machine that enables

consumers to borrow and, more recently, has tried to profit as they

run into trouble.

The system is powered by the companies that compile credit

reports based on consumers' borrowing histories. These

credit-reporting companies typically sell the data to financial

institutions offering loans, but as consumer debt has risen,

another type of offer is being pitched to tens of millions of

households.

"You may be completely debt free in only 24-48 months," said a

typical mailer from New York-based National Debt Relief, which

added that the offer was based on a credit report.

Companies like National Debt Relief seek out heavily indebted

consumers with a promise to help them get out from under it. But

regulators say these debt-settlement programs can leave customers

worse off, facing high fees, damaged credit scores and unexpected

income-tax bills.

Steven Boms, an adviser to the American Fair Credit Council, the

debt-settlement industry's trade body, said most people who enroll

in debt-settlement programs already are behind on payments. "The

only real alternative many of these consumers have to

debt-settlement is bankruptcy," he said.

Consumer debt, not counting mortgages, hit a record $4.02

trillion this year, a big reversal after Americans aggressively

paid down what they owed and lenders wrote off unpaid debts

following the financial crisis. As borrowers have fallen deeper

into debt, the amount enrolled in debt-settlement programs has

risen sevenfold, from $1.7 billion to $12 billion in the five years

that ended in March 2017, according to a survey by the

debt-settlement industry's trade group.

Data from credit-reporting companies has been used by some

debt-settlement firms to solicit consumers as their debt is rising

and when many are trying to sort out their financial situation.

Other firms flood mailboxes with offers of loans, but when

consumers call, the pitch can be very different.

'Get the client's guard down'

Ms. Tu, a 33-year-old business development manager in the San

Francisco Bay Area, said that after she was rejected for the

personal loan, a mailing from GreenLink Financial LLC arrived

offering a loan of about $60,000 -- twice what she wanted -- and at

a surprisingly low interest rate. But when she called the firm, it

turned her down for the loan and pitched her a debt-settlement

program instead, she said.

"They said, 'It's to help you get by because you're in a

financial crisis.' I'm not in a financial crisis, just trying for a

low interest rate," she told The Wall Street Journal.

Former GreenLink employees said only a small number of people

who responded to the company's mailings were offered loans.

Instead, they were pitched a debt-settlement program that GreenLink

sells on behalf of San Mateo, Calif.-based Freedom Debt Relief, the

former employees said.

GreenLink's salespeople were taught to "get the client's guard

down," according to a GreenLink telephone sales script reviewed by

the Journal. The Journal couldn't determine the date of the

script.

Most people who responded to GreenLink mailers were told they

would be called back after loan-underwriting checks had been made,

the former employees said. On that second call, the salespeople

were told to say, "I couldn't stop thinking about your file" and to

pledge, "I am going to make YOU my top priority today," according

to the script.

Then, the consultants were told to break it to the caller that

he or she didn't qualify for the loan offer the company mailed, the

script said.

"But this actually turned out to be GREAT NEWS!" the salespeople

were instructed to say, according to the script, before pitching

the debt-settlement program that offers "a payment which fits

perfectly within your budget."

Responding to an online complaint on Yelp by Ms. Tu, GreenLink

wrote in May that its agent had "handled the call with utmost

respect." It added that Ms. Tu did "not meet the minimum

requirements needed to get approved for any loan with our funding

source."

In response to a complaint on the Better Business Bureau

website, GreenLink wrote that debt-settlement "is only an option

for clients that we can't qualify for a loan."

The company didn't respond to requests for further comment.

GreenLink, of Santa Ana, Calif., sent about 27 million mailers

last year, according to estimates from data-provider Competiscan,

up from about 1.2 million in 2015, the first calendar year after

the company was formed.

Freedom Debt Relief in July agreed to pay $25 million to settle

a civil lawsuit filed by the federal Consumer Financial Protection

Bureau that claimed it charged consumers without settling their

debts as promised, and misled them about fees. Freedom didn't admit

or deny the allegations.

A representative of Freedom Debt Relief, which describes itself

as the nation's biggest debt-settlement company, didn't respond to

requests to comment. National Debt Relief also didn't respond.

Consumers who sign up for these programs are often told to stop

paying their credit-card bills and other debts and instead put the

payments in a special bank account, regulators say. Then the

debt-settlement company negotiates with creditors to try to get

them to reduce the consumer's debt.

Halting payments, though, can trigger big penalties and

potentially lawsuits by creditors and can hurt a person's credit

score. Even if the company persuades a creditor to reduce the debt

-- and there is no guarantee of this -- the customer may owe income

taxes on the amount of debt forgiven.

Taxes combined with fees these firms charge of as much as 25% of

enrolled debt could wipe out any savings from a reduced debt

balance. And a lower credit score that the strategy can trigger

could make future borrowing more expensive.

The trade group's Mr. Boms said companies marketing loans often

discover information during the loan-underwriting process, such as

additional debts, that wasn't known when a mailer was sent. The

group said last year that a survey of its members found

debt-settlement plans reduced consumers' debts by an average of

$2.64 for every dollar they paid the firms in fees.

Alternatives to debt-settlement companies include nonprofit

credit counseling services, which attempt to work with the borrower

and creditors to agree on a debt-management plan. These plans

usually don't reduce the amounts owed; instead, creditors may agree

to lower interest rates or waive fees. Credit counselors may charge

fees for some of their services.

Legal gray area

At least some debt-settlement firms have used information from

credit-reporting companies to pounce on troubled borrowers. The

federal Fair Credit Reporting Act allows the companies, including

TransUnion, Equifax Inc. and Experian PLC, to sell the data from

credit reports only for certain uses, such as firm offers of

credit. Debt settlement isn't specified in the law as a permitted

use of this sensitive financial information to solicit consumers,

and some experts consider it a gray area.

Some firms use the data to pitch debt-settlement plans,

according to mailings reviewed by the Journal and lawsuits filed by

consumers. The lawsuits reviewed by the Journal all were settled

confidentially by the firms.

Other firms first offer loans and then shift their sales pitches

to debt settlement, according to former employees of the companies

and telephone sales scripts reviewed by the Journal.

Jeff Sovern, a law professor at St. John's University in New

York, said that, based on his reading of the Fair Credit Reporting

Act, it isn't legal to use consumer-credit reports for

debt-settlement solicitations since "that's not a firm offer of

credit." He added that the law requires credit-reporting companies

to obtain certification from the entities with which they share

such information that it will be used for a lawful purpose.

Credit-reporting companies that sell data used to solicit

debt-settlement services "bear some responsibility" for the

practices of some in that industry because they should be vetting

the firms they sell the information to and how those firms use it,

said Chi Chi Wu, staff attorney at the National Consumer Law

Center, a nonprofit consumer-advocacy group.

TransUnion told the Journal it no longer supplies credit-report

data to the debt-settlement industry. A spokesman said the company

"historically...has sold prescreen data" to some debt-settlement

companies, adding that this complied with federal law because these

firms allowed consumers to delay payments for their services --

which TransUnion said was a form of credit -- or because they

actually offered loans.

An Equifax spokeswoman said the company "does not, as a matter

of policy, provide consumer-report information to companies who it

knows to be charging advance fees for debt or mortgage-assistance

relief." The spokeswoman didn't respond to questions about whether

Equifax sells information to debt-settlement companies that don't

charge advance fees, a group that includes the biggest players in

the industry. By law, for-profit companies that sell

debt-settlement services over the phone are barred from charging

advance fees.

Experian said it has never sold information from credit reports

to the debt-settlement industry for solicitation purposes.

CreditAssociates LLC, a Dallas-based debt-settlement company,

said it stopped receiving data from TransUnion last year, but sent

offers to consumers based on the company's information as recently

as last month.

"You are preapproved for a debt relief program that can save you

thousands of dollars," said a mailer sent earlier this year by

CreditAssociates. "This 'pre-screened' offer of credit is based on

information in your credit report."

Rick Burton, a co-founder of CreditAssociates, said its

debt-settlement offer in the mailer qualified as credit because

clients can pay the fees it charges in installments, rather than a

lump sum. This approach was approved by TransUnion compliance

personnel, he said.

A TransUnion spokesman said it doesn't provide legal or

compliance advice to its customers and doesn't approve customers'

mailers.

Prof. Sovern called the practice of letting customers pay fees

in installments a "quite imaginative" way of using the fair-credit

law's provision allowing the use of credit-report data for loan

offers "for a completely different purpose of debt-settlement

offers."

Concern about credit score

In some cases, sales pitches for debt-settlement programs appear

to minimize the risk to a consumer's credit score. Amanda Ricchio,

a 34-year-old accounting student in Racine, Wis., was mailed offers

for loans after she put a few thousand dollars of college costs on

her credit cards. The offers said they were based on credit

reports.

Ms. Ricchio called Simple Path Financial LLC, of Irvine, Calif.,

but was refused the 4.99% loan she had been pitched. Instead, she

said she was offered a debt-settlement program, which she was told

would cause only a "slight hit at first" to her credit score.

Ms. Ricchio, who had worked for a credit union where her father

was chairman, said she didn't believe the claim. "I know this kind

of program would actually cause serious damage to my credit score,"

Ms. Ricchio said.

Mr. Boms, the adviser to the debt-settlement industry trade

group, said the credit scores of the "vast majority" of people who

enroll in the programs would fall due to their existing financial

problems, whether or not they go this route.

Simple Path was founded in 2016 by Bradley Smith and Branden

Millstone and sells debt-settlement plans from another firm founded

by the two men, public records show. Mr. Millstone in an interview

said a "very large number of people" who respond to Simple Path

mailers are offered a loan, adding that he didn't have the exact

numbers.

People who do qualify for a loan may choose debt-settlement as a

better option than "putting a Band-Aid on their situation" by

taking on more debt, he added.

--Lisa Schwartz contributed to this article.

Write to Jean Eaglesham at jean.eaglesham@wsj.com and AnnaMaria

Andriotis at annamaria.andriotis@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

August 10, 2019 08:13 ET (12:13 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

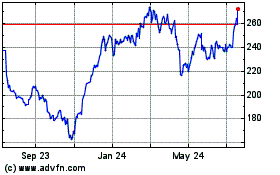

Equifax (NYSE:EFX)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Equifax (NYSE:EFX)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024