By Jacob M. Schlesinger

To see what President-elect Joe Biden thinks is wrong with the

economy today and how he would try to fix it, look to his

relationship with DuPont Co. For much of his life the company was

the largest employer and philanthropist in his home state of

Delaware, funding schools, libraries and theaters.

At age 29, Mr. Biden staffed his first Senate bid with DuPont

employees, who opened a campaign office on the highway built by and

named for the chemical giant. While bashing other big companies for

tax avoidance, Mr. Biden singled out DuPont as a "conscientious

corporation" for paying a higher rate. He celebrated his long-shot

1972 victory in the Gold Ballroom of the Hotel du Pont.

More than four decades later Mr. Biden, by then Barack Obama's

vice president, watched with concern as DuPont, struggling to boost

profits, was targeted by an activist shareholder, sold the hotel,

eased out its chief executive, merged with another company, split

into three pieces and cut its Delaware workforce by one-fourth.

Mr. Biden seldom publicly discusses DuPont by name, but in

private, according to aides, he regularly cites its restructuring

and downsizing as Exhibit A of modern capitalism gone awry. He

often bemoans what he believes to be corporate America's

prioritization of investors over workers and their communities.

His platform during this year's campaign was thick with policies

aimed at altering corporate behavior: a minimum corporate tax to

curb tax avoidance, penalties for shipping jobs overseas, measures

that make it easier for unions to form. "It's way past time we put

an end to this era of shareholder capitalism," he declared in a

July speech.

Mr. Biden can expect a backlash from many economists and

business leaders, who argue that his gauzy view of history

overlooks the inefficiencies of the old corporate titans -- which

ultimately harmed their workers and communities -- and ignores the

pressures of globalization and the dynamism of a modern economy

that allows healthier upstarts to replacing slumping behemoths.

"I don't think corporate America has very much to apologize

for," says John Engler, who was head of the Business Roundtable, a

trade group of the nation's largest companies, in 2016, when he

attended one of a series of meetings Mr. Biden hosted with CEOs and

economists during his vice presidency to try to hone a new

corporate-governance agenda.

"If companies get top-rated on other measures, if they're very

woke, it won't save them if they don't make money for investors,"

Mr. Engler, a former Republican governor of Michigan. "I don't

think there's a role for government in that."

Despite his criticism of corporate behavior, Mr. Biden is in

some ways closer to Mr. Engler than to the Democratic Party's left

wing, which wants to require big companies to obtain a federal

charter imposing a new list of requirements on executives such as

putting workers on boards. Mr. Biden often indicates he'd rather

change corporate America not through regulatory fiat but moral

suasion by persuading executives to take a broader view.

A career politician, Mr. Biden has no direct business

experience. But he often says his perspective is shaped by his

roots in Delaware, its business-friendly laws and its long history

as the preferred incorporation locale for large U.S. companies.

DuPont's looming presence there has been a major influence. "He

views DuPont as a proxy for a responsible corporate citizen, for a

lot of American corporations in the '50s, '60s, and into the '70s,"

says Don Graves, who was Mr. Biden's policy adviser during the

Obama administration and now works on his transition team. "He felt

that over time DuPont and others began shifting away from that

framing, because of the focus on quick shareholder returns."

There are parallels between Mr. Biden's outlook on commerce and

politics, both worlds he often portrays as more benign in his youth

-- sometimes glossing over the turmoil, or the dominance of white

men -- as an era when CEOs had a stake in their communities, and

lawmakers compromised across party lines. He often suggests that a

calming, compromising leader such as himself could revive a more

genteel age, a view some critics consider naive.

"It used to be that corporate America had a sense of

responsibility beyond just CEO salaries and shareholders --

corporate America has to change its ways," Mr. Biden told a group

of donors at a July fundraiser. He then added: "It's not going to

require legislation. I'm not proposing any."

Mr. Biden is swimming against a tide of American business

orthodoxy that is often traced to an influential 1970 essay by the

late Nobel laureate economist Milton Friedman, "The Social

Responsibility of Business Is to Increase its Profits." Like many

on the left, Mr. Biden blames it for ushering in an era when

executives purportedly sacrificed workers and communities for the

sake of next quarter's bottom line -- breaking what he calls the

"basic bargain" of shared prosperity. "We act like Milton Friedman

is still alive and well on dealing with corporate policy," he told

a group of Indiana donors in June.

"DuPont is a classic example of what Milton Friedman did," said

Ted Kaufman, a former DuPont engineer who helped develop Corian

countertop material, joined Mr. Biden's staff in 1972, and now

co-chairs his transition team. For Mr. Biden, he added, DuPont's

battle with activist investor Nelson Peltz and his Trian Fund

Management LP "was an epiphany."

Trian says Mr. Biden's diagnosis is wrong. DuPont's

"underperforming relative to its peers...negatively impacted all

stakeholders including employees, customers, and communities," a

Trian spokesperson said. Trian's goal was "returning the company to

best-in-class status...for the benefit of all its constituents, not

just its shareholders."

The smaller DuPont left after all the restructuring takes a

similar view. "Over its 200-year history DuPont has evolved," says

spokesman Dan Turner. "The one constant has been deploying our

science and innovation to remain a leader...committed to delivering

sustainable value to all the customers, employees, shareholders and

communities we serve."

Many academic economists and corporate-governance experts say

Mr. Friedman is still mostly correct, although the debate has

evolved in recent years, with more executives saying they now look

beyond shareholders, and more shareholders saying they look beyond

short-term profits.

The rise in so-called ESG investing -- in which funds rate

companies by environmental, social, and governance benchmarks in

addition to profitability -- suggests the market may be moving past

the ostensible focus that Mr. Biden and other critics decry.

The Business Roundtable last year issued a statement declaring

that CEOs should "lead their companies for the benefit of all

stakeholders -- customers, employees, communities and

shareholders." That replaced a 1997 directive that a company's

"paramount duty...is to the corporation's stockholders."

Yet for all the talk of change, most companies still give

priority to shareholder returns, an emphasis most analysts consider

inevitable. "What's changed over time is that there's a view that a

lot of customers care about the environment and care about social

issues, and companies need to respond to that," says Steven N.

Kaplan, an economist at the University of Chicago, Mr. Friedman's

academic home when he published his essay. "That said, if you do

all of that without maximizing shareholder value, you're going to

be uncompetitive." Those forces are driven in by part by the spread

of globalization that intensified after DuPont's heyday, says Mr.

Kaplan, and can't be reversed "unless the whole world does it."

Charles Elson, a University of Delaware finance professor,

agrees. "If you're accountable to everyone, you're accountable to

no one, and you create a mess," he said. "Some would argue that's

where DuPont found itself."

Mr. Elson made that point to Mr. Biden when the two appeared on

a panel discussion at the university's newly created Biden

Institute in 2017 titled "Win-Win: How Taking the Long View Works

for Business and the Middle Class." Activist shareholders like Mr.

Peltz were often "a symptom of problematic management," and gave

the economy its dynamism by using their profits "to create new

companies, to create new ideas," Mr. Elson said.

A skeptical Mr. Biden replied: "What evidence is there of

that?"

Delaware itself offers evidence of how capital and labor can be

reallocated from declining to productive sectors. As DuPont shrank,

Delaware developed a thriving financial sector. A study by the

Economic Innovation Group, a think tank, shows Delaware's new

business startup rate outpaces the national average -- in part from

ventures by former DuPont executives and scientists. Over the past

three decades, total employment in Delaware has grown about 25%,

even as the share of employment from manufacturers like DuPont has

fallen in half, to about 6%. At the same time, however, income

growth has slumped, according to Moody's Analytics, underscoring

the Biden argument that workers have lost out from those

changes.

Mr. Biden's father moved his family from struggling Scranton,

Pa., to Delaware in 1953, where he ultimately ran a used-car

dealership, attracted by prosperity attributable in good part to

DuPont. Founded in 1802 as a gunpowder maker, its products such as

nylon, Teflon, Freon, Lucite, Mylar and Kevlar revolutionized

consumer and commercial life. At its peak in 1990, DuPont employed

27,000 in Delaware -- one of every 10 workers.

The company was affectionately dubbed "Uncle Dupie," and family

members funded schools and hospitals, ran dozens of charitable

foundations, made up their own bloc of lawmakers in the state

legislature and periodically were elected governor. It built and

ran a country club for employees, and a theater and hotel for

Wilmington.

Consumer activist Ralph Nader wrote in a 1971 investigative

report that "virtually every major aspect of Delaware life...is

pervasively and decisively affected by the DuPont Company, the

DuPont family, or their agents." He and other critics accused it of

using that clout to suppress unions, avoid taxes, and discriminate

against minorities. The company clashed over the years with

regulators, antitrust enforcers, and activists over such things as

groundwater contamination, hazardous waste and its control of the

cellophane market.

DuPont leaders brushed aside those attacks and cultivated an

image of a corporation steered by a broad civic mission. "Business

is a means to an end for society, and not an end in itself," CEO

Lammot du Pont Copeland, great-great-grandson of the founder, wrote

in a 1967 corporate publication. "Therefore business must act in

concert with a broad public interest and serve the objectives of

mankind and society."

That's how many Delawareans, including Mr. Biden, saw the

company. DuPont was one of the first companies to provide employees

health insurance and pensions. In his 2007 autobiography, Mr. Biden

recounted boyhood memories of neighbors who "wore tie clips

imprinted with the company trademark: a little oval with DuPont in

the center. There was a saying among the DuPont dads: 'The oval

will take care of you.' "

After winning his upstart bid for senator in 1972, Mr. Biden

quickly developed a good relationship with DuPont, meeting with top

executives at least twice a year and speaking regularly to

gatherings of the company's rising stars. In 1975, the new senator

bought a 10,000 square-foot mansion built and once owned by the du

Pont family. He helped DuPont win federal grants and earmarks.

DuPont executives and employees were modest contributors to Mr.

Biden's Senate campaigns, as well as to those of his Republican

opponents, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. They

gave him a total of $46,725 in his four campaigns elections between

1990 and 2008, the years covered by Center data, and $12,525 to his

GOP challengers.

"He helped us a lot," says Charles Holliday, DuPont's CEO from

1998 to 2008, now chairman of Royal Dutch Shell PLC. There were

also clashes over taxes and regulation: Mr. Holliday recalls

lobbying Mr. Biden unsuccessfully to drop support for legislation

on safety regulation of rail transport. Still, he adds, "He talked

a lot about the company, how it cared about its employees."

Then, through the 1990s and early 2000s, DuPont saw its profit

margins squeezed as many product lines such as nylon became

commoditized by Asian competitors and the company's vaunted

innovation culture struggled to come up with new high-profit

patent-protected chemicals to replace them. It tried to pivot

toward biotechnology and agriculture, but had trouble catching up

with leaders in the field such as Monsanto Co. By the early 2000s,

DuPont's Delaware employment had fallen to less than half the 1990

peak.

DuPont faced a new challenge in 2013, when Mr. Peltz's Trian

took a 2.2% stake worth $1.3 billion and demanded big changes. A

college dropout from Brooklyn, Mr. Peltz first won Wall Street fame

trading junk bonds in the 1980s. He and two others later founded

Trian, which went on to shake up corporate icons such as H.J. Heinz

Co., Wendy's Co., and Bank of New York Mellon Corp. Mr. Peltz said

DuPont was "destroying shareholder value" by clinging to its hotel,

country club, and theater, and maintaining a large R&D budget

with few visible returns. He decried its complex blend of seven

business lines, demanding it break into separate, more streamlined

parts.

Facing off against Mr. Peltz was CEO Ellen Kullman. She grew up

in Wilmington, attending the same Saturday evening mass as the

Bidens. With degrees in engineering and business, she was climbing

the ladder at General Electric Co. before getting lured back home

to DuPont.

Mr. Biden met Ms. Kullman a few times as she rose through the

corporate ranks and later served on the Obama administration's

Council on Jobs and Competitiveness. Mr. Biden saw her as someone

focused on the long term and employees, said Mr. Graves. At a 2015

luncheon with Chinese President Xi Jinping and American business

leaders, the vice president singled out Ms. Kullman as "the best

one."

Other companies gave Mr. Peltz board seats without a fight. Ms.

Kullman and Trian negotiated privately for months to reach an

agreement, but those talks broke down, triggering one of the

hardest-fought proxy battles in years.

Ms. Kullman noted that since she'd become CEO in January 2009,

DuPont shares had outpaced the broader market. She dismissed

attacks on the hospitality business, whose costs she said were

minimal, and defended R&D as providing value for investors

willing to wait a few years to see returns. She ran local newspaper

ads warning DuPont's role as a "proud pillar of the greater

Wilmington community" was under attack. In a close 2015 vote,

shareholders rejected Trian's proposal to replace four of the 12

directors.

Mr. Peltz lost the battle but won the war. Later that year,

DuPont fell far short of its earnings guidance. Management blamed

the miss on a strengthening dollar and a sharp slowdown in big

agriculture markets such as Brazil. But investors had grown weary

of repeated profit shortfalls and called for deeper cuts. Ms.

Kullman resigned amid board pressure.

Her successor, consulting closely with Mr. Peltz, announced at

the end of 2015 a complex plan to merge with Dow Chemical Co., then

to break the combined company into three smaller parts, mirroring a

Peltz demand. Shortly after the merger announcement, DuPont said it

would lay off 1,700 of its remaining Delaware employees, leaving

around 4,400. The Wilmington News Journal ran a column headlined:

"Uncle Dupie is Dead."

The new smaller, more-focused DuPont makes specialty-sciences

products ranging from adhesives to biomaterials.

Five years after the DuPont-Dow merger was announced, the

combined market value of the current DuPont and the two other

companies spun out of that process is roughly the same as it was

back then, lagging behind the S&P 500, which is up about 70%

over the same period. Total jobs fell about 9% through 2019 to

around 92,500.

Most analysts following the company say the transformation was

worth it. "They're far more efficient and lean than they would have

been," says David Begleiter, managing director for chemicals and

agriculture for Deutsche Bank Securities Inc.

Still, this past February DuPont's board, disappointed with the

pace of restructuring, shook up management yet again.

Mr. Biden didn't comment publicly on DuPont's turmoil but in

private was frustrated at Ms. Kullman's departure and the company's

breakup, said Mr. Graves.

Ms. Kullman, now CEO of Carbon Inc., a 3-D printing technology

company, recalls running into Mr. Biden a few times after departing

DuPont. When they crossed paths, she says Mr. Biden would indicate

to her his displeasure.

In January 2016, he decided to make a major declaration on the

failings of 21st century American capitalism at the World Economic

Forum in Davos, Switzerland. He recounted to a room full of CEOs a

conversation that he said he'd had with a top corporate

executive.

The men met, in Mr. Biden's telling, on the Amtrak platform in

Wilmington, the politician heading southwest to Washington, the

business leader northeast to New York. "I said 'Where are you

going?' " Mr. Biden recalled. "He said: 'To meet with some

sniveling little guy on Wall Street who's gonna tell me that I have

to increase profitability in the next quarter, or I'll be

downgraded.' "

The executive complained that would force him into "short-term

decisions that were not in the long-term interest of his company,"

Mr. Biden said, then lectured his audience: "A lot of you corporate

leaders don't like me saying that, but you know it's true."

Biden aides said the company was DuPont, but couldn't identify

the executive.

Around then Ben Harris, the vice president's chief economist,

and Mr. Graves organized nearly a dozen meetings with CEOs,

investors, labor leaders, and scholars in which Mr. Biden delved

deeper into the intersection of finance and business. Jeff Zients,

an Obama economic adviser now co-chairing the Biden transition

team, was also involved.

The guest lists were heavy with outspoken critics of so-called

short-termism and shareholder focus, including BlackRock Inc. CEO

Larry Fink, Virgin Group founder Richard Branson and Jeffrey

Sonnenfeld, a Yale School of Management professor. At one meeting,

University of Massachusetts Lowell economist William Lazonick

argued buybacks explained why workers' wages lagged behind their

productivity, which became a regular theme for Mr. Biden, though

other economists dispute it.

Aides say Mr. Biden's original goal was to persuade the Obama

administration to end its term embracing an ambitious agenda for

reorienting American business. Some administration economists

balked: They said curbing stock buybacks wouldn't raise wages or

capital spending. Officials also concluded there wasn't time to

write new regulations, and legislation stood no chance in the

Republican-controlled Congress.

Shortly after leaving office, Mr. Biden compared the effort to

the famous observation from British philosopher G.K. Chesterton

about religion -- "it's not that Christianity has been tried and

found wanting; it's been found difficult and left untried." He

added: "that's kind of where we are in a policy sense."

--Jacob Bunge in Chicago contributed to this article.

Write to Jacob M. Schlesinger at jacob.schlesinger@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

November 23, 2020 14:03 ET (19:03 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

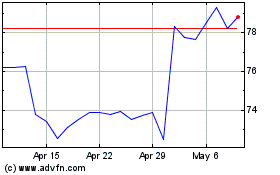

DuPont de Nemours (NYSE:DD)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

DuPont de Nemours (NYSE:DD)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024