By Sara Germano

BERLIN--German efficiency has taken a hit this year as many of

the country's most recognizable corporate names have faced

setbacks, hurt by a slowing local economy, questionable business

decisions and trouble shifting to a digital world.

In the past week, Deutsche Bank AG abandoned its global

ambitions and initiated layoffs, the chief executive of BMW AG said

he would step down and sharp profit warnings from Daimler AG and

BASF SE rattled markets.

That news followed the continuing legal woes facing Bayer AG for

its acquisition of Monsanto, the maker of weedkiller Roundup, and

continued fallout for auto makers from the diesel-emissions scandal

and depressed global new car sales. Meanwhile, German blue chips

from software maker SAP SE to industrial giant Thyssenkrupp AG have

announced a combined tens of thousands of job cuts this year.

One in three large public companies in Germany's DAX index have

reported profit warnings, job cuts or restructurings, or are

dealing with legal disputes or investigations from authorities.

More firms based here are slipping from the rankings of the most

valuable global companies, leading consulting firm Ernst &

Young to conclude this month that "German companies are losing

their importance."

Some companies are facing unique challenges, but broader trends

are also affecting them. Contributing to the nation's woes,

analysts say, are the effects of global trade disputes on Germany's

export-oriented economy, increased pressure to digitize and a

degree of complacency after years of robust growth.

"There is a crisis at the moment, the German economy was so good

for such a long time, people thought we'd go on and go on and go

on," said Markus Schön, managing director of DVAM Asset Management

in Detmold, Germany.

The economy grew just 0.7% in the 12 months through March, far

behind others in the eurozone, and earlier this year Berlin slashed

its forecast for 2019 growth domestic product to 0.5% from 1.8%.

"German companies were not prepared for this situation," Mr. Schön

said.

Key among them are the German auto makers, which were hit by a

collapse in demand for diesel vehicles and a global slowdown in car

sales as they are spending heavily on electric and autonomous

vehicle development.

Both BMW and Daimler lowered their financial guidance this year

and the latter--maker of Mercedes-Benz luxury vehicles--issued two

profit warnings in the last three weeks, while Volkswagen AG said

it would cut 7,000 jobs. In turn, the difficulties of large car

makers have filtered down through the network of smaller suppliers

and service providers whose fortunes are directly tied to the

sector's health.

Volkswagen has also struggled to move beyond an

emissions-cheating scandal that first surfaced in 2015. In March,

the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission sued the auto maker and

former Chief Executive Martin Winterkorn for defrauding U.S.

investors. And a month later, German prosecutors indicted Mr.

Winterkorn and four others for fraud.

Other German firms say their problems are closer to home. Last

month, days after issuing a profit warning attributed to aggressive

competition from European low-cost carriers, Deutsche Lufthansa AG

Chief Executive Carsten Spohr said the airline had made missteps

navigating the local short-haul market, including efforts to

capitalize on the 2017 bankruptcy of ex-rival Air Berlin.

"Did we underestimate the complexity? We did," he said. In an

effort to reassure investors, Mr. Spohr reasserted the company's

commitment to being dependable and efficient. "In the end, we're

boring. We're German."

Another factor behind Germany's corporate troubles is the

country's legally mandated board structure, which flanks the

management board with a powerful supervisory board, half of whose

members represent workers. While such checks and balances have

helped maintain labor peace at large companies, they can also

inhibit quick decision-making and discourage risk-taking.

"On the one hand, it can be an advantage to have a strong CEO,

who can react quickly in times of crisis," said Christian Lawrence,

a partner at Brunswick Group in Munich. "Whereas if you have a

German system, the CEO is one of many making decisions and there

must be consensus for things to be done."

Hubert Barth, chief executive of Ernst & Young Germany, said

some German blue chips are stumbling over "the transformation of

the economy toward more digitized business models."

On the surface, German companies and the government are adamant

about their commitment to digitization. This week, German economics

minister Peter Altmaier traveled to Silicon Valley to meet with

executives from Alphabet Inc.'s Google, Apple Inc. and others, part

of a continuing effort to raise Germany's profile in digital

industry.

There is a pervasive feeling, analysts and executive say, that

German companies can't keep up with the large tech giants from the

U.S. and elsewhere. This is also partly attributable to strong

limitations that German and European privacy laws put on companies'

ability to collect, store and monetize user data.

"Tell me one company in Germany which is playing a role in

platforms, the area of Facebook and Amazon," said Mr. Barth of

Ernst & Young. "There's no obvious German company that plays a

significant role."

At an internal Bertelsmann SE meeting in May, executives from

across the media conglomerate presented their strategies for

working with, and competing against, American tech firms.

"We will never be able to gather the same amount of data as

Google, Facebook or Amazon," said one executive at the meeting.

"This is a fact, and we just have to deal with it. They are on

their own planet."

Troubles at Germany's large companies aren't a perfect guide to

the health of the national economy. While the country is home to

many global brands, the backbone of its industry is the vast number

of small- and midsize private businesses known as the

Mittelstand.

Those traditionally family-owned private firms haven't

encountered the same challenges as large public companies, Mr.

Lawrence said, in part because their management system is less

complex and they aren't subject to the restrictions of the public

market.

But this has brought other negative consequences. According to a

report from the International Monetary Fund this week, about 60% of

corporate assets and profits in Germany are generated by

privately-owned firms, contributing to rising wealth inequality in

Germany, the strongest in Europe behind the Netherlands and

Austria.

"The concentration of privately held and publicly-listed firm

ownership in the hands of industrial dynasties and institutional

investors is especially prevalent in Germany," the IMF report

said.

Write to Sara Germano at sara.germano@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

July 12, 2019 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

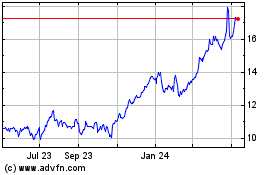

Deutsche Bank Aktiengese... (NYSE:DB)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

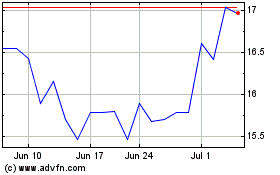

Deutsche Bank Aktiengese... (NYSE:DB)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024