By Liz Hoffman and David Benoit

For Americans checking their retirement accounts, the market's

swings during the first quarter were a horror show. For Wall

Street's traders, they were a windfall.

Big banks' trading desks posted their strongest results in years

during the first three months of 2020 -- when the deepening

coronavirus crisis wreaked havoc on the markets -- buying and

selling trillions of dollars worth of stocks and bonds, commodities

and interest-rate products.

Goldman Sachs Group Inc.'s debt traders had their best

three-month stretch in five years, pulling in nearly $3 billion.

Bank of America Corp.'s stock traders' $1.7 billion in revenue was

a quarterly record.

Those firms and others had to contend with traders working from

backup sites and from makeshift setups at home. The most volatile

conditions in years collided with a prohibition on congregating in

close quarters like trading floors.

Executives also had to balance the opportunity for profits with

the safety of staff. JPMorgan Chase & Co. was slow to act,

leading to a coronavirus outbreak on its Manhattan stock-trading

floor. Overall, the four major investment banks that have reported

quarterly results so far made $23 billion in trading revenue, 31%

more than the same period a year ago.

"March was the most extraordinary month of my career," said Jim

Esposito, a 25-year veteran of Goldman and co-head of its trading

arm. "We had both a spike in client volumes and spike in

volatility. That's a very potent combination that had been missing

for quite some time."

The results were one of the few bright spots in otherwise bleak

financial reports. Profit fell between 45%, at Bank of America, and

89%, at Wells Fargo & Co., after banks set aside billions of

dollars to cover expected losses on loans in what is likely to be a

painful recession. Morgan Stanley, slated to release results

Thursday, will be the last of the major U.S. banks to give a

first-quarter update.

The results show how Wall Street has changed since the financial

crisis. Today's banks carry smaller inventories of securities than

they once did. Wary of risk and regulatory snafus, they turn it

over more quickly and don't make the same proprietary bets they did

before the 2008 crisis.

Instead, they mostly stand in between clients who want opposite

sides of the same trade. In Wall Street speak, they "intermediate

risk."

That spared them from the worst of the declines in asset prices

and allowed them to profit by charging small fees on a surging

number of trades and lending hedge funds money to finance their own

positions.

While banks took huge trading losses in 2008 -- and many were

too weak to do much to help clients -- they are in stronger shape

today.

"People are desperate to be able to turn their portfolio over

and if you don't have to deal with your own issues, you are going

to do well." said Paco Ybarra, the head of Citigroup Inc.'s

institutional clients group.

The surge is unlikely to last, said Octavio Marenzi, chief

executive of Opimas, a consultant to financial-services companies.

"It was easy to make money" in the first quarter, he said, "but it

was, in all likelihood, a one-time hop. You often see this: Lots of

trading on the way down, but once you hit the bottom, it's dead

quiet."

Goldman's trading revenue rose 28% to $5.16 billion. Its

algorithmic group, which writes code to automatically buy and sell

securities, at one point was on pace to double its 2019 revenue,

according to a person familiar with the matter. Groups that help

clients wager and manage volatility in asset prices flourished,

too.

Coming into the year, Goldman had been easing up on the big bets

that once drove its trading profit, lowering both the size and

riskiness of its securities inventory. That proved lucky as the

pandemic hit, Chief Financial Officer Stephen Scherr said, leaving

the bank freer to jump into the market.

"We came into this crisis with a more manageable risk profile,"

he said. Goldman's total assets grew by 10% in the quarter, topping

$1 trillion, with much of the additional heft now sitting in its

trading operation.

Wall Street traders have complained for years about calm

markets, which depress the volume of trades and make it harder to

eke out profits on the ones that do come in. "Volatility wasn't

just low," Mr. Esposito said. "It had pretty much been

eliminated."

That changed in March.

Stock prices fell, then surged, and fell again. Wall Street's

"fear gauge," a measure of volatility, surpassed previous records

set in 2008. Debt investors started getting choosier about bonds,

charging far more to lend to lower-rated borrowers than safer ones,

after a decade of making little distinction.

Those market jumps opened up opportunities for the hedge funds

and other asset managers that are clients of big-bank trading

operations.

Banks "woke up and all of a sudden these hedge fund clients

started whipping it up like butter," said Bill Smead, chief

investment officer at Smead Capital Management Inc., which counts

JPMorgan and Bank of America among its largest holdings.

Bank of America's adjusted trading revenue rose 22% from a year

ago. Chief Financial Officer Paul Donofrio said clients flocked to

products that bet on the global economy, such as interest-rate

swaps and currency products. Trading in bonds and loans were weaker

at the firm, and its rivals, which had to revalue them to bake in

the growing risk of defaults.

At Citigroup, where trading revenue rose 39%, Mr. Ybarra said

the demand seemed to roll from one product to the next. In early

March, U.S. Treasurys -- and products that are tied to them -- were

going haywire. The Fed intervened to smooth that out, but other

corners of the market seized up.

JPMorgan posted a 32% rise in trading revenue, but also took a

$951 million loss on derivatives it held on its books.

The volatility struck as the banks, and their clients, were

forced to thin out their trading floors and send many employees

home or to alternate sites. Banks had to decide how many traders

could be remote and still keep the markets functioning -- and

profits flowing.

On April 2, just 30 Goldman Sachs traders, out of thousands,

were at its lower Manhattan headquarters. The floor was similarly

sparse at Citigroup, whose chief executive, Michael Corbat, said

the dislocation had led to fewer bumps that he anticipated.

"The plumbing is actually working pretty well," he said "We

probably all would've been skeptical" before the virus hit.

--Ben Eisen contributed to this article.

Write to Liz Hoffman at liz.hoffman@wsj.com and David Benoit at

david.benoit@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 15, 2020 18:56 ET (22:56 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

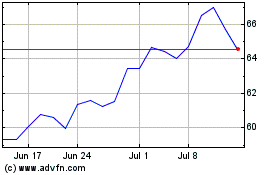

Citigroup (NYSE:C)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Citigroup (NYSE:C)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024