By Nicole Friedman

The myriad companies of Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway Inc.

have run completely independently of each other for decades. That

isn't always the case any longer.

Top executives from Berkshire units now gather regularly to

share strategies and best practices. Some of these companies

participate in purchasing cohorts to take advantage of group rates

for items like travel and raw materials. Last year, employees from

more than 40 Berkshire businesses met in the firm's headquarters

city of Omaha, Neb., to discuss sustainability.

The rise in internal collaboration, which executives rarely

discuss publicly, hints at what the firm might look like when Mr.

Buffett is no longer running it as chairman and CEO.

Last year the company's subsidiary CEOs started reporting to Mr.

Buffett's lieutenants, Ajit Jain and Greg Abel, rather than to Mr.

Buffett. And at the subsidiary level, roughly one-third of

Berkshire's business units have announced a new CEO in the past

five years as an older generation of managers has retired or

stepped back into chairman roles.

"Even though we're in different industries and have different

business models, there's so much that connects us," said Mary

Rhinehart, CEO of Berkshire's building-products maker Johns

Manville. "Why wouldn't we take advantage of the talent across the

Berkshire Hathaway organization?"

While many other conglomerates combine departments and seek

savings when they buy businesses, Berkshire historically hasn't.

Its home builder Clayton, for example, isn't required to buy bricks

from Berkshire's Acme Brick. But Berkshire companies now are

communicating and working together more than ever, thanks largely

to efforts begun in 2013.

Starting that year, Berskhire's 60-odd CEOs began meeting yearly

in Omaha to discuss common challenges like cybersecurity and

hiring. Tracy Britt Cool, Mr. Buffett's former financial assistant

and the CEO of Berkshire unit Pampered Chef, organized the first

roundtable.

Collaboration among Berkshire companies "is grass roots," Mr.

Buffett said in an interview last week. "I'm certainly glad to see

it, but I don't promote it."

Mr. Buffett seeks to buy well-run companies and leave them

alone, allowing Berkshire CEOs to set their own strategies, pay

plans and employee benefits. Berkshire's subsidiaries employ nearly

390,000 people around the world, and before the roundtables, many

Berkshire CEOs hadn't met each other in person.

"The best cooperation is voluntary," Mr. Buffett said. "That's

not a change in the culture, though. It's sort of a sign of the

culture. It really is people thinking like owners and exercising,

in a sense, their independence."

Separate from the annual roundtables, there is also now a

Berkshire Hathaway Sustainability Summit that has grown from 37

attendees representing 24 Berkshire businesses at the first summit

in 2013 to about 140 participants from more than 40 Berkshire

companies and their subsidiaries at last year's event. In addition,

a group of sustainability-focused employees at various Berkshire

companies speak about once a month to share ideas and

strategies.

There are also formal networks for Berkshire CFOs and for

executives in areas including human resources and

cybersecurity.

The sustainability summits grew out of informal conversations

among some subsidiaries, said Susan Farris, vice president of

sustainability and corporate communications at Berkshire's carpet

and flooring company, Shaw Industries Group Inc., which hosted the

first event in 2013.

"With a group of Berkshire companies, there's a significant

level of comfort that you might not have attending a broader

conference," she said. "We share priorities and values."

Purchasing groups, which allow subsidiaries to take advantage of

Berkshire's scale, grew out of the CFO meetings more than a decade

ago, Ms. Rhinehart said.

Some Berkshire businesses overlap with each other and even

directly compete for customers. Berkshire owns four furniture

companies, four jewelry companies and a variety of insurance units.

In addition, a number of Berkshire companies operate in the housing

and construction industries, including Shaw, Clayton, paint maker

Benjamin Moore & Co. and real-estate brokerage firm

HomeServices of America.

"It's not as if there's a weekly or quarterly call with

[housing] industry participants," said Jeff Pederson, CEO of CORT,

Berkshire's furniture-rental company. "But the nice thing about the

group of men and women that Warren has is they're all so very

willing to lend a hand."

One aspect of Berkshire that could become more centralized in

the future is health care.

Haven, Berkshire's health-care joint venture with Amazon.com

Inc. and JPMorgan Chase & Co., is in its early stages but aims

to reduce health-care costs for the three companies' employees.

That could mean requiring Berkshire units that currently buy their

own health insurance to change their strategies.

Meantime, current Berkshire executives have already tapped into

the CEO network. Dan Calkins, who started as Benjamin Moore's CEO

in January after 32 years with the company, called another

subsidiary's manager in late 2018 to learn how that unit sets its

compensation and incentives for senior executives.

See's Candies CEO Brad Kinstler, who has worked at three

Berkshire subsidiaries, said last year that the annual CEO meetings

have sparked new working relationships.

"It used to be more just individual contacts that you would

have," said Mr. Kinstler. Now, "there's an open exchange of ideas

on a number of different things, and I think it's very

helpful."

Write to Nicole Friedman at nicole.friedman@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 04, 2019 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

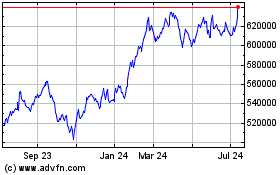

Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE:BRK.A)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

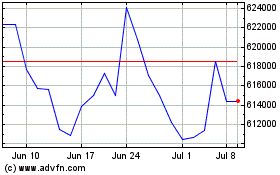

Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE:BRK.A)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024