By Corrie Driebusch

Many businesses are struggling. Millions of Americans are out of

work. But the IPO market is the hottest it's been in years -- and

2020 could be its biggest year ever.

With three months left on the calendar, U.S.-listed initial

public offerings have raised nearly $95 billion through Wednesday,

according to data provider Dealogic. That already surpasses the

totals of every year except 2014 since the tech bubble in 2000.

It's nipping at the heels of 2014, when IPOs raised $96 billion,

more than a quarter of it by Alibaba Group Holding Ltd.

Bankers, lawyers and executives say that if the frenetic pace

keeps up, 2020 will eclipse the tech-boom years of 1999 and 2000,

when investors feverishly pumped money into burgeoning internet

stocks before they crashed to Earth.

Investors are gobbling up these new listings, with this year's

IPOs posting the biggest gains during their trading debuts since

2000, at 22% through Wednesday. On average, 2020 IPOs have risen

roughly 24% from their original prices.

The fortunes of the IPO market have never been more divergent

with the state of the U.S. economy. The coronavirus pandemic sent

businesses into free fall, pushing unemployment to its highest

level ever this spring. But it also caused a shift in the economy.

With everyone relying more on technology for work, school and

everyday communications, the value of companies providing related

services pushed higher. And with low interest rates limiting

returns on traditionally safe investments like bonds, investors are

looking for ways to make money wherever they can.

This year, more than 80% of the money raised by initial public

offerings falls into three buckets: healthcare, technology and

newly popular blank-check companies -- shell firms whose only

purpose is to acquire a private target and take it public. That is

the most concentrated the IPO market has been since 2007, according

to Dealogic, when new listings of banks and lending institutions

flooded the market before the financial crisis.

More than 235 companies have joined the U.S. public markets this

year, on track for the most since 439 companies went public in

2000, according to Dealogic. They'll soon be joined by giants

Airbnb Inc. and Palantir Technologies Inc., which will go public

later this year after long tours as private companies.

Even Warren Buffett, America's most well-known value investor,

who typically avoids investing in startups, is participating.

Mr. Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway Inc. bought roughly $735

million in shares of data-warehousing company Snowflake Inc.'s

public offering. Shares finished their first day of trading on

Sept. 16 at more than $250 apiece, more than double their IPO price

-- making it the biggest tech IPO of the year. At the end of that

first day, the company had a market value of $70.4 billion. Mr.

Buffett's stake was worth nearly $1.6 billion.

The state of the IPO market is a huge reversal from just a few

years ago, when many venture capitalists and CEOs had declared the

initial public offering all but dead. For more than a decade,

companies opted to raise giant amounts in the private markets, made

possible thanks to large funds such as SoftBank Group Corp.'s $100

billion Vision Fund. Staying private allowed startups to avoid the

hassle of regulatory disclosures and prevented them from having to

answer to public shareholders. In 2016, IPOs and their investors

raised less than $25 billion.

Now companies are growing wary of staying private too long after

watching some marquee IPOs, like Uber Technologies Inc. and Lyft

Inc., struggle last year. Public investors are also rewarding

high-growth companies with big valuations they are unlikely to

fetch in the private markets -- a change from a few years ago.

Companies are now trying to hit a sweet spot, going public after

they've had a chance to mature a bit but before their strong growth

trajectory has slowed.

The market is less ecstatic than the feverish tech bubble that

infused massive amounts of capital into internet companies like

Pets.com, which then burned through cash and collapsed just months

later, devastating the stock market. Still, companies that had

previously written off a 2020 IPO are forging ahead this year,

hoping to ride the wave. Others are planning public debuts in the

first half of 2021.

New alternatives

The process of going public is changing as well, after remaining

mostly the same since the 1980s.

"It used to be a formulaic conversation about the path to going

public," said Bennett Schachter, who heads global alternative

capital solutions at Morgan Stanley. Those stages tended to be a

series of fundraising rounds, perhaps a private placement to

pre-selected investors, a so-called crossover financing round that

involves investors that mostly work with public companies, followed

by an IPO. "Now there is this broader and increasingly

well-accepted spectrum of alternatives."

Blank-check companies have exploded this year as an alternative

to the traditional IPO, accounting for more than 40% of the money

raised in IPOs this year. That compares to an average of 9% over

the previous 10 years, according to Dealogic.

Kevin Hartz, co-founder of Eventbrite Inc., was an early

investor in Airbnb, Uber and Pinterest Inc. This year he decided to

launch a blank-check company.

His first official meeting with bankers about his venture was in

mid-June, he said. Less than two weeks later, he said, he filed

confidentially with the Securities and Exchange Commission and by

the end of July his filing was public. Roughly 60 days after that

June meeting with bankers, Mr. Hartz's blank-check company had

raised $200 million and almost immediately started reaching out to

founders of companies with whom he may want to merge. He said he

was amazed how quickly he was able to turn his idea for a

blank-check company -- also known as a special-purpose acquisition

company, or SPAC -- into reality.

"SPACs have the possibility to be the leader in the future," he

said, noting one of their biggest benefits for founders is that in

a reverse merger, a startup can provide shareholders with earnings

and growth projections for the future. In a traditional IPO that

isn't allowed.

Another alternative more companies are exploring is going public

through direct listings -- in which they list employees' and

investors' existing shares on the open market, allowing them to

potentially cash out their stakes. That lets companies avoid

investment banks' big fees for underwriting an IPO, but doesn't

allow them to raise additional money.

Palantir, the big-data company co-founded by billionaire Peter

Thiel, will complete a direct listing later this month in one of

the biggest market debuts of the year, at an expected value of $22

billion. Software company Asana Inc. is also planning to go public

via a direct listing later this month.

Previously, just two major companies had ever gone public that

way. Spotify Technology SA, which went public in 2018, spent much

of its first two years public trading below its first-day closing

price, though its shares have soared since this spring. Slack

Technologies Inc., which went public in 2019, remains below its

first-day closing level.

The other blockbuster name set to go public this year,

house-sharing giant Airbnb, had also planned a direct listing for

its 2020 IPO. It had to change plans when the pandemic forced

executives to raise additional money, according to people familiar

with the matter. A spokesman for Airbnb declined to comment.

The rules could soon change. In late August, regulators approved

a proposal from the New York Stock Exchange to let companies raise

capital through direct listings, though the approval recently hit a

snag due to objections from a large investor group. The option

would remove a key barrier for companies, making direct listings

even more attractive, according to people familiar with the matter.

Nasdaq Inc. has filed a similar proposal.

"There's been more innovation in the last two years than in the

last two decades," said Stacey Cunningham, the president of the New

York Stock Exchange. "There is a renaissance in the IPO

market."

Social-distancing measures to avoid the virus have also shaken

up the process. The typical IPO roadshow spanned a grueling eight

to 10 days when executives traveled the globe and peddled their

wares to prospective investors in conference rooms. Now, roadshows

are typically shorter and entirely virtual, enabling more investors

to participate than ever before.

When online insurance broker SelectQuote Inc. listed its shares

on the NYSE in May, it used a four-day virtual roadshow. "Who

would've thought you could raise $350 million in your pajamas from

the comfort of your home?" the company's CEO, Tim Danker, said.

Market shifts

Pandemic-induced shifts in the public and private markets helped

usher in the IPOs. As the country shut down earlier this year, the

availability of private funding became more scarce. Some executives

struggled to raise money at the valuations they wanted. In the

second quarter, there was a sharp rise in the number of startups in

the private market completing so-called down rounds, or funding

rounds where the valuation based on the share price dropped

compared with the prior round.

The public funding markets, including the IPO market, also

seized up briefly in early March, but swift moves by central banks

around the world restarted the flow of money. After the S&P 500

hit its 2020 low in late March, a bond-buying intervention from the

Federal Reserve helped companies raise cash -- and enthusiastic

bets from individual investors helped drive up shares of big tech

companies and propel major indexes higher. Bankers and corporate

executives took advantage of the optimism, rushing out companies

that had been aiming for early spring IPOs.

To ensure these IPOs went smoothly, companies and their bankers

lined up institutional investors, including T. Rowe Price Group

Inc. and Fidelity Investments, to commit to buying large portions

of the company either ahead of the IPO or as part of the public

offering. Fund managers told The Wall Street Journal that after a

choppy spring that hammered some of their portfolios, they were

happy to be able to buy into IPOs, which tend to outperform the

broader stock market.

Shares of companies that went public in late May and early June

soared, leading a bevy of new issuances this summer. The New York

Stock Exchange said August, typically a sleepy time for IPOs, was

its busiest month since October 2013.

This spring also brought a surge in financing for blank-check

companies -- a sign that there's more demand for IPOs this year

than there are companies able to quickly go public.

While the niche has been around for many years, it often wasn't

taken seriously. Their legitimacy was bolstered over the past year

after high-profile companies like Virgin Galactic Holdings Inc. and

DraftKings Inc. went public through reverse mergers with

blank-check firms.

Their structure tends to offer a big payday to the blank-check

company's sponsors even if shares fall. Typically, those sponsors

are awarded shares equivalent to about 20% to 25% of what is raised

in the IPO at the time the target is bought. Some newer blank-check

offerings are reducing their cut of the deal. Blank-check IPOs also

haven't always performed well; historically, many traded below

their offer prices, and deals they strike aren't always approved by

shareholders. The newest generation of blank-check sponsors say

they want to change that.

The case of electric-truck startup Nikola Corp. shows how risks

remain. One of this year's high-profile IPOs through a blank-check

company, it is now embroiled in legal and stock-trading woes, with

the Justice Department examining allegations that it made

exaggerated claims about its technology. A spokeswoman for Nikola

declined to comment. Shares have tumbled, but remain above the

level they traded when their merger deal was announced.

Meanwhile, struggling streaming-video service Quibi is

considering a reverse-merger with a blank-check company to go

public, The Wall Street Journal reported Monday.

Vivek Ranadivé is no stranger to capitalizing on an IPO boom. In

1999, the tech entrepreneur brought his company, Tibco Software

Inc., public and watched shares double during their first day of

trading. Since then, the software entrepreneur sold Tibco to a

private-equity firm in 2014, stayed involved in the world of tech

investing and became majority owner of the Sacramento Kings.

In February, Mr. Ranadivé attended the NBA All-Star Game and ran

into some investors who told him he should try his hand at a

blank-check company. At first, he was skeptical.

"A SPAC was a sleazy thing 20 years ago," he said. Then the

pandemic hit with full force, and the timing seemed perfect to

launch a SPAC of his own. So he did.

This summer, Mr. Ranadivé raised more than $480 million for his

new blank-check company. Now he is on the hunt for a target to

buy.

--Graphics by Ana Rivas

Write to Corrie Driebusch at corrie.driebusch@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 25, 2020 13:01 ET (17:01 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

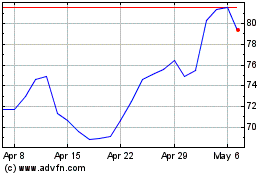

Alibaba (NYSE:BABA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

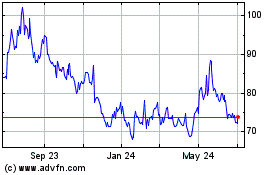

Alibaba (NYSE:BABA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024