By Ted Alcorn

The crowd at the New Orleans health clinic in late June filled

the seats and overflowed into the wings. Louisiana Gov. John Bel

Edwards was there, as were employees from Gilead Science's

affiliate Asegua Therapeutics. They had gathered to launch a plan

for the statewide elimination of hepatitis C, which killed more

than 17,000 Americans in 2017.

The event, however, wasn't prompted by the discovery of a new

cure. Officials were unveiling a new way of paying for an existing

therapy.

It is rare for government officials and companies to celebrate a

financial agreement. But in recent years, progress in addressing

hepatitis C has been hampered not by a lack of innovative drugs but

by a marketplace that fails to make those drugs widely available.

When breakthrough therapies that rapidly cure the chronic infection

were introduced starting in late 2013, manufacturers charged prices

in the tens of thousands of dollars per course of therapy. Many

insurers proved willing to pay, bringing the drug companies tens of

billions of dollars.

But many health-care payers with fixed budgets such as state

Medicaid programs and correctional health systems balked at the

prices, and set criteria that effectively reduced the number of

infected patients eligible for treatment. Louisiana exemplified the

problem: An estimated 39,000 people in the state's Medicaid program

or in its prisons are infected with hepatitis C, but in 2018 just

over 1,000 were treated.

So shortly after her appointment in 2016, Louisiana Secretary of

Health Rebekah Gee decided it was time for a new approach. "I found

it unacceptable that people would get sick and die from a disease

that is curable," she says.

Early on, Dr. Gee played hardball, openly exploring whether to

ask the federal government to invoke a century-old provision of

patent law that would force the manufacture of the drugs for the

public good, at a vastly discounted price. The proposal, strongly

opposed by drugmakers, may have helped bring them to the

negotiating table, where a framework for a voluntary agreement

began to emerge.

Sealed after nearly two years of subsequent negotiation, the

final agreement effectively made Asegua the primary provider of

hepatitis C therapies for the state's Medicaid and correctional

populations for the next five years.

In return, the drug company agrees to de-link the volume of

drugs it provides from the payments received. That means instead of

selling the medication by the dose, the company will provide as

much as the state can dispense to the Medicaid and correctional

populations. This arrangement has been likened to a Netflix

"subscription," where the price customers pay isn't linked to the

volume of movies they stream, and their total consumption isn't

capped. The state will effectively pay a fixed price to access all

of the drugs it can use. The agreement sets this amount at roughly

$60 million, equivalent to what the state paid in the 2019 fiscal

year.

Crucially, where Louisiana previously saw costs increase with

every patient it enrolled in treatment, this arrangement

incentivizes the state to identify and treat as many people as

possible because the marginal cost of each additional patient is

essentially zero. With the new contract signed, the state has

promised to treat 80% of both Medicaid and correctional populations

by 2024.

If it achieves that goal, by treating more than 31,000 people in

five years, the cost per patient will be less than $10,000. Experts

say that is likely lower than the price paid by many other states

but still highly profitable for Asegua, as the company has long

since recouped its investment in hepatitis C therapies. Ingredients

to make a course of treatment are estimated to cost less than

$100.

For Asegua, which declined to comment on the price per patient,

the deal gives it guaranteed income and a chance to claim credit

for helping expand treatment at a time when public anger about high

drugs prices is growing. "Partnering with Louisiana on this unique

model was born from our commitment to making our innovative

medicines accessible to those who need them," the company said in a

statement.

Enormous promise

Health-policy experts say the agreement -- the first of its kind

for a U.S. state -- could serve as a model for other health-care

payers increasingly looking for innovative ways to manage costs and

pay more directly for health itself.

A month after Louisiana's agreement was revealed, Washington

state announced a similar arrangement with drugmaker AbbVie. Other

states have expressed interest in these approaches, too, though

none have confirmed they are developing their own models. "We're

all sort of learning from each other and trying to figure out what

works best," says Judy Zerzan, chief medical officer of Washington

state's Health Care Authority.

Although the hepatitis C epidemic is unique in many respects --

there is a large and clearly defined population of infected people

who lack access to treatment, all of whom can be effectively cured

with a single therapy, and multiple, competing manufacturers

capable of providing it -- experts say the subscription model could

have applications for other diseases, as well.

Rena Conti, an associate professor at Boston University's

Questrom School of Business who helped Louisiana develop its

agreement, says the model might be applied to purchases of

medications for pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV, known as PrEP.

She also points to products that are on the horizon, including gene

and stem-cell therapies to treat children with congenital disorders

like sickle cell anemia.

The U.K., meanwhile, recently announced it will test a

subscription agreement to purchase antibiotics. Unlike Louisiana,

which sought to expand treatment, the U.K. hopes to reduce

drugmakers' incentives to widely market their products, limiting

unnecessary use that can contribute to antimicrobial

resistance.

These endeavors are part of a larger wave of innovative payment

models that attempt to better align the price of drugs with the

scale and pace of benefit they provide. Oklahoma, Colorado, and

Michigan recently obtained federal approval to negotiate new

value-based agreements with drugmakers, like scaling payment for a

drug to the health benefit it yields. And the Senate's leading

effort to reduce drug prices, introduced by Sens. Chuck Grassley

and Ron Wyden in late July, would allow installment plans for some

expensive one-time therapies, so insurers could gradually pay for

them as treated patients accrue benefit from them.

"There is enormous promise in the idea," says Josh Sharfstein, a

vice dean at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

"Way too much of the discussion on drug pricing is about the cost

per pill, and way too little is about whether we're really

improving the health of the community,"

Clearing hurdles

Louisiana's payment model may sound simple, but the route to it

was far from straightforward.

In addition to getting drugmakers to the negotiating table,

Louisiana had to overcome federal regulations meant to keep drugs

affordable for the poorest patients. By law, drugmakers must offer

their drugs to state Medicaid programs at the best price they sell

to any other payer. It wasn't until June that the Centers for

Medicare and Medicaid Services authorized Louisiana to implement

its subscription agreement outside of the "best price" rule, which

could have forced Asegua to revise its Medicaid contracts with

other states.

When the Louisiana agreement went into effect on July 15,

Cassandra Youmans, a doctor who has been treating patients with

hepatitis C at University Medical Center New Orleans since 2008,

combed through her records to identify Medicaid patients who had

previously been denied treatment.

In the first week, she started 65 of them on medications, more

than she has ever initiated in a comparable period. And a

once-labyrinthine process of getting insurers' approval was now

instantaneous and nearly seamless: She could see a patient for the

first time, order a prescription at the pharmacy downstairs and

begin the patient's treatment immediately.

"This new program has revolutionized treatment," she says.

Making medications accessible is a crucial step, but officials

acknowledge that on its own, it isn't sufficient to end the

hepatitis C epidemic. Most people with hepatitis C are early in

what can be a decadeslong progression of disease, and are unaware

they are infected. To help identify those patients, Louisiana is

asking health-care providers to begin offering opt-out testing to

people who visit their emergency departments, among many other

changes.

In Australia, which adopted a subscription model for hepatitis C

treatment in 2016 but didn't pair it with broad screening of the

population, treatment numbers spiked at first, but then tapered

off.

"Subscription models are great if they are a holistic program

that includes screening, linkage to care, and treatment," says

Homie Razavi, who directs the nonprofit Centers for Disease

Analysis Foundation, which has modeled hepatitis C elimination

strategies for both the Australian and Louisianian governments.

"But if the focus is only treatment, it's going to fizzle out in a

few years."

Mr. Alcorn is a writer in New York. Email him at

reports@wsj.com.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 13, 2019 10:05 ET (14:05 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

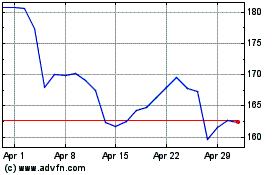

AbbVie (NYSE:ABBV)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

AbbVie (NYSE:ABBV)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024