By Julie Wernau

Two months into the coronavirus epidemic in China, tens of

millions of people are still under quarantine and much of the

economy remains in a deep freeze.

Yet China has largely succeeded in keeping its stores filled

with food and other essentials -- even in hard-hit places like the

city of Wuhan -- a crucial factor in maintaining public order

throughout the crisis.

To do that, China relied on mandates from central authorities

against hoarding and profiteering. Private companies, including

JD.com Inc. and Walmart Inc., rerouted trucks and located supplies

that otherwise might not have made it to market.

After Beijing called for an increase in face mask production,

manufacturers canceled holidays for workers and jacked up wages to

increase production of basic medical supplies. When Beijing issued

orders against price gouging, companies looked for sudden price

spikes and cut off guilty shopkeepers, or found ways to make more

products available.

Shopping app Pinduoduo Inc. got more farmers to use their online

marketplaces, enabling them to sell more widely. By targeting

soon-to-expire foods that might ordinarily have been thrown away by

suppliers, Walmart was able to locate a massive batch of cucumbers

in Yunnan province. Staff members worked through the night at a

distribution center to test and sort the cucumbers for delivery to

stores the next morning.

"The only element of physical commerce that really stayed close

to normal is the supermarket," said Michael Norris, a

Shanghai-based research and strategy manager at Agency China, a

market research firm. "The supermarket has really been the

lifeblood of the community during this event."

Other countries, including the U.S. and Japan, are grappling

with how to keep supplies available as the coronavirus spreads. In

the U.S., supermarkets have rationed some items and are considering

cutting operating hours and tapping volunteers to deliver food.

It isn't clear if other countries will want to go as far as

China, whose central government intervenes often in commerce. China

has also had problems of its own making to deal with -- including

navigating the rigid quarantine restrictions enacted by

Beijing.

Panic buying did appear in some parts of the country and some

products have remained in short supply. There was also some luck in

the epidemic's timing, since many households were stocked up for

the Lunar New Year holiday.

Food inflation countrywide rose 21.9% in February from a year

earlier. But much of the increase was due to pork prices, which

have been battered by African swine fever.

It could have been worse. Lu Jie, who runs a small shop in

Beijing selling everything from Twix bars to dried fruits, said she

initially had to rely on supplies left over from the prior season.

Many products couldn't get into Beijing because of quarantine

restrictions.

This week, she said, more of her old suppliers were reappearing,

as trucks found more ways to get through roadblocks. With business

still slow, she said she already had most of what she needed.

A few weeks earlier, it seemed likely that China would endure

crippling goods shortages.

So many people in rural areas were forbidden to enter and exit

their communities that vegetables couldn't be shipped out. Some

places disallowed harvesting of certain foods outright, including

green onions and cauliflower, citing a need to contain the

epidemic.

Roads became nearly impassable due to government blockades. Many

truck drivers were forced into quarantine because they had been in

exposed areas. Food shipments dropped dramatically at ports, with

international deliveries canceled.

In response, China's government released more than 300,000 tons

of pork from central and local strategic reserves, adding more meat

to the market.

Relying on a Ministry of Commerce emergency commodity database,

authorities reached out to hundreds of businesses to gather

information about supplies of rice, vegetables and other products,

and began connecting buyers with available sellers.

To make sure goods got through roadblocks, the government

established a "green channel" system that allowed truck drivers to

travel between cities with special passes. Some local governments

hired truck drivers to keep supplies flowing.

The city of Chongqing, in central China, hired a local trucking

firm called Circle Logistics Co. that normally serves factories

operated by Foxconn Technology Group and Corning Inc. to deliver

vegetables, drugs and face masks, said Robin Zheng, its owner.

"Moving vegetables isn't our usual work," said Mr. Zheng. "But

this is the job right now: delivering food."

To ensure buyers didn't hoard and store owners didn't engage in

price-gouging, Beijing announced strict prohibitions on such

activities, while some local governments punished outlets that

jacked up prices. Costco Wholesale Corp. and other grocery chains

agreed to limit the number of customers allowed into stores and to

stop selling some popular products to lower store visits.

Jingkelong Supermarket in Beijing set up lines for customers to

enter, with each person standing one meter apart. Customers were

given cards to return upon exit, allowing another person to

enter.

Pinduoduo, which is especially popular among consumers in

smaller cities, promoted a recently-created platform that helps

farmers find alternative buyers. Ning Qiang, a 32-year-old

businessman from Sichuan province, used the service after figs he

sourced from farms -- which can only survive for 10 days after they

are picked -- went unsold during the Lunar New Year. He eventually

found buyers.

JD.com said when inventories in its warehouses for products like

rice, flour and oil started getting tight, it was able to source

additional supplies from offline businesses -- including mom and

pop stores -- that were open and closest to customers. In many

cases, an order on JD.com was supplied by a courier coming directly

from the customer's local convenience store.

Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. said its various food-delivery

platforms hired thousands of people who were unable to return to

their usual jobs and put them to work delivering supplies to

people. At one point when all roads were blocked in an area where a

father who was desperate for baby formula lived, sorting station

manager Ning Yang carried the baby formula herself, walking more

than two kilometers to deliver it to the buyer's door.

--Xiao Xiao and Trefor Moss contributed to this article.

Write to Julie Wernau at Julie.Wernau@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 13, 2020 05:45 ET (09:45 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

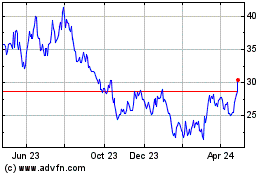

JD com (NASDAQ:JD)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

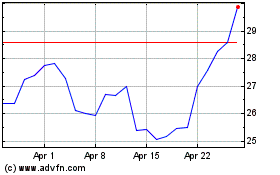

JD com (NASDAQ:JD)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024