By Richard Rubin

Multinational corporations are devising new strategies to keep

their taxes low, saving billions of dollars by navigating around

attempts by the U.S. and European countries to tighten the tax

net.

Companies that prospered for years with low tax rates are

learning how to keep them that way, even as political pressure

builds to tax them more. They are doing so by moving intangible

assets such as patents and trademarks between subsidiaries and

across borders.

The moves don't fundamentally change a company's operations or

pretax profit, but they can generate significant new deductions

that can offset income for years or ensure that income gets taxed

at lower rates.

"The large multinationals continue to find ways to keep their

taxes on their global income low," said Brad Setser, a senior

fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.

More than a dozen major U.S. companies -- including ViacomCBS

Inc., Gilead Sciences Inc. and Activision Blizzard Inc. -- have

disclosed such maneuvers, reporting total future tax savings of at

least $13.6 billion, according to a review of recent securities

filings that companies completed prior to the coronavirus

pandemic.

Before the U.S. and Europe changed their tax laws over the past

few years, American companies had a cut-and-paste model for global

tax planning. They transferred intellectual property -- or the

rights to use it -- to foreign subsidiaries.

Because taxation is tied to places where value is created,

companies could reduce their tax bills by moving those assets, and

the profits they generated, to subsidiaries outside the U.S. or

other high-tax countries. In many cases, those subsidiaries

ultimately reported their profits in places without corporate taxes

such as Bermuda or the Cayman Islands.

"The location of intellectual property is more of a tax-planning

exercise than movements of people and activities," said Thomas

Horst, managing director of Horst Frisch, a consulting firm that

works on international corporate transactions.

Before the 2017 tax law, overseas income theoretically was

subject to U.S. taxes of as much as 35%. But companies could

postpone payment of those taxes as long as the profits remained in

segregated accounts at a foreign subsidiary. For years, companies

achieved single-digit tax rates on their non-U.S. income and

indefinite deferral of U.S. taxes.

In 2017, Congress lowered corporate rates and created a

deduction designed to encourage technology companies and exporters

to keep assets in the U.S. It imposed a one-time tax of as much as

15.5% on past overseas profits and created a minimum tax of 10.5%

on future foreign profits, whether or not companies left them

abroad.

Separately, European countries collaborated to end maneuvers

such as the Double Irish, which companies used to funnel profits

via Ireland to no-tax jurisdictions such as Bermuda. European

countries, responding to their citizens' concerns about tax

avoidance, also made it harder for companies to park their

intellectual property in tax havens without having real operations

alongside them.

Corporate securities filings reveal that U.S. companies have

found new ways to keep their tax bills low. A common tactic: A

subsidiary in one country sells intellectual property to a

subsidiary in another. Normally, that would produce taxable income

in the first country and deductions in the second.

But if that first country has no corporate income tax, or no tax

on such asset sales, there is no immediate tax bill. In the second

country, companies get to deduct the cost of that purchase. They

can do that over many years, generating annual deductions.

That stream of deductions lowers future tax bills in the

intellectual property's new home, and it is a strategy encouraged

by Irish law. In 2019, Ireland reported a 93% increase in

investment that was driven by movement of intellectual

property.

Media conglomerate ViacomCBS offers an example. The company was

born of the 2019 merger between Viacom and CBS. As part of the

merger, it moved some intellectual property from the Netherlands to

the U.K., according to an executive familiar with the

transaction.

The transaction wasn't subject to Dutch taxes and will generate

deductions over 25 years in the U.K., the executive said. The

company does significant business in the U.K. and will continue to

be a taxpayer there, the executive said. The result: a $768 million

tax benefit.

Similarly, Gilead Sciences, a biopharmaceutical firm based in

Foster City, Calif., completed "an intra-entity asset transfer of

certain intangible assets from a foreign subsidiary to Ireland" in

late 2019, according to securities filings. The result was a $1.2

billion deferred tax benefit.

"Gilead has realigned its intellectual property holdings in

compliance with guidelines and requirements in the various

jurisdictions where we conduct business," spokesman Chris Ridley

said in a written statement. "The majority of our innovative

pipeline intellectual property resides in the U.S."

Activision Blizzard, which makes the "World of Warcraft"

videogame, moved assets to a U.K. subsidiary in October 2019,

recording a net benefit of $230 million. Activision declined to

comment.

Not all of the moves involved transfers between foreign

jurisdictions. Some companies have begun using the U.S. as the base

for their intellectual property, an aim of some authors of the 2017

tax law.

"The U.S. is relatively more attractive than it ever was

before," said David Rosenbloom, an international tax lawyer at

Caplin & Drysdale in Washington.

For example, Garmin Ltd., a navigation-technology company,

announced a February 2020 transaction to move intellectual property

from Switzerland, where it is based, to the U.S. As part of the

change, the company's U.S. entities will pay royalties to those in

Switzerland.

"That lowers the amount of income recognized in the United

States, increases it in Switzerland," Douglas Boessen, the

company's chief financial officer, told analysts Feb. 19. "That

gives us a favorable income mix by jurisdiction during that license

period."

As a result, the company forecasts a 10% tax rate, down from

15.5% in 2019.

Among the incentives for basing intellectual property in the

U.S. now: Companies can deduct expenses for research, which was

difficult if not impossible when the property was kept

offshore.

The new law also created a deduction to encourage companies to

record more of their profits in the U.S. in return for tax rates as

low as 13.125%, instead of the standard 21% rate.

Transfers of intellectual property to the U.S. -- unthinkable

before 2017 -- show how the gap between U.S. and foreign tax rates

has narrowed.

"The goal is more tax neutrality," said George Callas of Steptoe

& Johnson LLP, who was the tax-policy aide to House Speaker

Paul Ryan during the writing of the 2017 law, known as the Tax Cuts

and Jobs Act.

But there are still reasons to keep intellectual property

overseas. Once a company moves those assets to the U.S., it cannot

move them back out again without paying significant taxes.

"If you somehow decide later that you didn't want that IP in the

U.S., it's going to be really difficult to get it back out again,"

said Albert Liguori, a managing director at Alvarez and Marsal

Taxand, an advisory firm. "That's what leads most companies" to

keep their assets abroad.

Tax professionals caution that the international tax system

remains in an unusual state of flux, making it difficult for

companies to make the forecasts needed for long-term decisions.

Countries are still trying to craft new rules on where corporate

profits are taxed, and U.S. tax rules and low rates could change

quickly if Democrats retake Congress and the White House in

2020.

"It's a little hard to see, if you're advising a company, where

it goes, " Mr. Rosenbloom said. "You have to take it almost day by

day, week by week."

Write to Richard Rubin at richard.rubin@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 08, 2020 08:14 ET (12:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

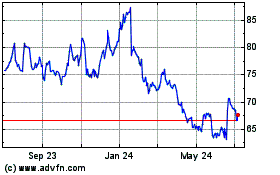

Gilead Sciences (NASDAQ:GILD)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

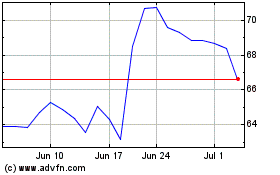

Gilead Sciences (NASDAQ:GILD)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024