By Richard Rubin, Paul Hannon and Sam Schechner

An agreement by wealthy countries to impose minimum taxes on

multinational companies faces a rocky path to implementation, with

many governments likely to wait and see what others, especially a

divided U.S. Congress, will do.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen hailed the deal, reached by

finance ministers of the Group of Seven leading nations over the

weekend in London. She called it a return to multilateralism and a

sign that countries can tighten the tax net on profitable firms to

fund their governments.

The agreement represents a turning point in long-running

negotiations over where and how corporate profits should be taxed.

The deal would impose a minimum tax of at least 15% and give

countries more authority to tax the profits of digital companies

like Apple Inc. and Facebook Inc. that dominate global markets but

pay relatively little tax in many countries where they operate.

While the impact on tech companies remains uncertain, some

welcomed the prospect of a more uniform global regime. Nick Clegg,

Facebook Inc.'s vice president of global affairs, said on Twitter

that the deal is a "step toward certainty for businesses" when it

comes to taxes.

New tests come soon and in the months ahead, as details get

hashed out and governments see which country goes first. Those that

move ahead before others could damage their revenue bases and

companies, according to tax experts, and those lagging behind a

global consensus could be hurt too.

"While we may see a deal, it's then potentially 18 months or

more to push it into the domestic law of each of the countries,"

said Monika Loving, national practice leader for international tax

services at advisory firm BDO. "In terms of revenue impact, we're

maybe two years off seeing tax administrations collecting any

additional revenue."

At the center of attention, some tax specialists, lawyers and

officials said, is the U.S. Congress.

In countries with parliamentary systems, governments can quickly

deliver on pledges, turning them into local laws and regulations.

In the U.S., however, a slim Democratic majority in the House, an

evenly split Senate, antitax Republicans and procedural hurdles

complicate passage.

Other countries may be reluctant to change their laws or remove

taxes that hit U.S.-based tech companies without seeing Congress

move first.

U.S. lawmakers may take the reverse view, wary of raising taxes

or ceding tax authority to other nations without assurances of a

complete global accord that would minimize any disadvantages of a

U.S. corporate headquarters.

Democrats can pass some changes on their own but have

differences among themselves over tax policy. The Biden

administration has also called for raising the corporate tax rate

to 28% from 21% and setting the minimum tax on U.S.-based companies

at 21% to fund other initiatives. And some Democrats have balked at

those higher rates.

Republican votes may be needed if countries' minimum tax changes

necessitate renegotiating tax treaties, which require two-thirds

votes in the Senate for ratification.

The top tax-writing Republicans in Congress -- Rep. Kevin Brady

of Texas and Sen. Mike Crapo of Idaho -- noted that the U.S.

already imposed a form of minimum tax at 10.5% in 2017 and that

other countries haven't followed.

"We continue to caution against moving forward in a way that

could adversely affect U.S. businesses, and ultimately harm

American workers and jobs at a critical time in our country's

economic recovery," they said.

The G-7, which comprises Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan,

the U.K. and the U.S., agreed that businesses should pay a minimum

tax rate of at least 15% in each of the countries in which they

operate.

They also agreed to new rules that change which countries can

tax which income in the increasingly digital economy. Those new

rules will focus on large global businesses that have a profit

margin of at least 10%. The right to tax 20% of profits above that

threshold would be shared among governments.

The deal faces an early test in the Group of 20 leading

economies, which includes all of the G-7 and a number of large

developing countries such as China, India, Brazil and South Africa.

Finance ministers from the G-20 meet in Venice in early July, and

an overhaul of global tax rules is on the agenda.

Buy-in will also have to come from a broader group of 135

countries in what is known as the Inclusive Framework. Some

countries with very low tax rates -- such as Ireland, with a 12.5%

charge on profits -- are reluctant to sign up. The U.S. has

proposed tax changes that would penalize companies from countries

that don't impose the minimum taxes.

"We'll have to convince the other great powers, especially the

Asian ones. I am thinking in particular of China," France's finance

minister, Bruno Le Maire, said in a television interview this

weekend. "Let's face it, it's going to be a tough fight. I am

optimistic that we will win it because the G-7 is giving us

extremely powerful political momentum."

While G-7 members agreed on the outlines of a new rulebook, they

also left some unfinished business.

A number of countries from Europe raised the stakes in the

long-running talks by announcing separate national levies on

digital businesses, hoping those would pressure the U.S. into an

international deal. In retaliation for what it saw as

discrimination against U.S. companies, the U.S. announced punitive

tariffs on imports from those countries, although it suspended

those tariffs until the end of this year.

The G-7 didn't agree on a schedule for removing those levies, a

sign that decision makers aren't sure exactly when new tax rules

might come into play. In their final statement Saturday after two

days of meetings, G-7 ministers said they would work on a path to

removing the levies that will be tied to the new rules coming into

force.

The broader changes, if enacted, would affect many of the

world's largest and most profitable companies, particularly in the

tech sector. But the removal of the digital-services taxes would be

a silver lining for tech companies. They have long said they would

prefer an international resolution on taxes that result in higher

bills to a patchwork of national levies.

Some tech executives have expressed worry that countries will

attempt to hang onto their digital-services taxes even with a

global deal on corporate taxes.

Matthew Schruers, president of the Computer & Communications

Industry Association, which represents companies including Alphabet

Inc.'s Google and Facebook Inc., applauded the G-7 agreement

Saturday. However, he cautioned, "The work is not finished until

the digital taxes that unfairly target U.S. businesses have been

removed," he said.

Many big tech companies, including Apple Inc., Alphabet and

Facebook have in recent years already reported effective tax rates

roughly around the 15% minimum rate proposed by the G-7, according

to securities filings.

Companies that are below the rate, such as Apple, could see a

potential increase in its tax bill under the proposed deal in some

years.

The tech company reported an effective global tax rate of 14.4%

for the year ended Sept. 26, 2020, citing lower tax rates on

foreign earnings.

A spokesman for Apple declined to comment.

Write to Richard Rubin at richard.rubin@wsj.com, Paul Hannon at

paul.hannon@wsj.com and Sam Schechner at sam.schechner@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

June 06, 2021 18:14 ET (22:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2021 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

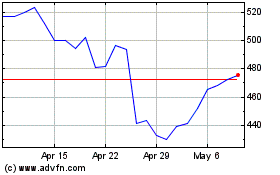

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024