By Nicole Nguyen

The same coronavirus post kept popping up on my Facebook feed

last week. People in my network -- a friend's mom, a college

classmate and another "friend," who I'm not sure I've even met in

person -- had somehow obtained identical symptom and treatment

guidance from Stanford University.

There were details about an at-home testing technique involving

breath holding, as well as something truly dubious about sipping

water every 15 minutes. On March 12, the university said the text

was "not from Stanford."

Overnight, the viral post disappeared from the social

network.

Then, last weekend, an urgent message circulated through group

chats. The text falsely suggested people stock up before a

soon-to-be-announced national quarantine. Please share with your

networks, the message pleaded. On Sunday night, the National

Security Council shot down the speculation on Twitter. "Text

message rumors of a national #quarantine are FAKE. There is no

national lockdown."

Many people spreading these fraudulent posts have good

intentions. Everyone's trying to keep up with an ever-shifting

situation. (Remember last week? That feels like years ago.) And

they want to help each other. But the current regularity of

forwarded falsehoods is revealing: Any absence of good information

leaves room for a lot of terrible information.

The World Health Organization recently described this moment as

an " infodemic." We're getting virus news through a fire hose --

push notifications, TV, social media, hearsay through our networks.

There's misleading or inaccurate information at every turn, despite

companies' efforts to remove it. And as social networks crack down

on misinformation, it's growing in grass-roots channels, like text

and email.

Many people, confused by all the noise, are still searching for

answers. So, how do we wade through the onslaught? I called some

experts for help.

Focus on factual information from official channels. "I would

strongly urge people to get their information from sources like the

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or highly respected news

organizations. Everything else should be regarded as suspect," said

Angie Drobnic Holan, editor in chief of the Poynter Institute's

nonprofit fact-checking site PolitiFact.

In other words, focus more on facts from official sources, and

less on chasing down every shred that might be true, says Claire

Wardle, a research fellow at Harvard's Berkman Klein Center and

co-founder of First Draft, a nonprofit dedicated to studying

misinformation.

The more people are exposed to a falsehood, the more likely they

are to accept it as true -- what Dr. Wardle refers to as the

"familiarity backfire effect."

In that vein, my WSJ colleagues are regularly updating a guide

to what scientists and health officials know about coronavirus, as

well as answering readers' most pressing questions.

The primary sources that reporters rely on include the World

Health Organization and U.S.-based CDC. Both agencies provide virus

outbreak updates and guidance on how to stay healthy from public

officials. The CDC mobile app serves this information right to your

phone. Pro tip: Turn on the app's filter for "Coronavirus Disease

2019." The WHO launched a WhatsApp messaging service that provides

situation reports in real time, as well as information on

coronavirus myths. (If you are on your phone, this link takes you

right to the app to sign up.)

Many state and local authorities are also excellent resources,

Ms. Holan said. The CDC website includes links to every accredited

state and health department across the U.S.

The most-shared misinformation seems plausible. The most recent

wave of misinformation reads more like rumors that could be true or

are close to the truth rather than outright falsehoods, according

to Dr. Wardle. Fraudulent messages are often attributed to "a

friend of my friend who works in the government" or other

authoritative entities.

"A lot of this stuff is not malicious. It's people trying to

help each other, but it's false," she said.

Misinformation is moving from public to private channels. The

internet's largest social networks are aggressively moderating

coronavirus content. On March 16, Facebook, Google, LinkedIn,

Microsoft, Reddit, Twitter and YouTube sent a joint statement: "We

are ... jointly combating fraud and misinformation about the virus

[and] elevating authoritative content on our platforms."

The crackdown has unintended consequences. "People started

moving into spaces where they can't be tracked. The only thing

holding things together is people holding other people

accountable," said Dr. Wardle.

Encrypted messaging services, like WhatsApp, have struggled to

police misinformation sent through their systems. To maintain

users' privacy, the messages stay encrypted end to end, with no

server in the middle being able to read their contents. To mitigate

misinformation, moderators must be able to see the message's

contents. On Wednesday, WhatsApp launched a coronavirus website,

asking users to not forward a message if they aren't sure it's

true.

Apple's iMessage is end-to-end encrypted in a similar way, so

the company can't see the contents of a message to identify whether

it is misinformation or spam.

Pause before you share. "Misinformation tends to play on

people's fears, " said Ms. Holan. In other words, if you're feeling

strongly -- either you're scared or feel like there's an urgent

need to take action -- that might be a sign that the information is

dubious.

If people stopped sharing entirely and just relied on official

sources, we'd likely be better off, Dr. Wardle said. "It's like

washing our hands. We have to get into new habits about sharing

only what we know," she said.

Look up which outlets covered the news. As mentioned previously,

focus on the facts. But if you want to do your own homework, here's

how.

Before sharing information, do a quick search to see if other

outlets have reported the same thing, advised Jon Keegan, an

adjunct assistant professor at the Columbia University School of

Journalism. He is currently an investigative data journalist at The

Markup. (He's also a former Wall Street Journal visual

correspondent.)

Mr. Keegan suggested GroundNews, an app and website that shows

you how many outlets have covered top stories at a glance. The more

widely a story is covered, the more credible it likely is.

Most important, Mr. Keegan noted, look at the source named in

those outlets' reporting. If multiple reports link to the same

questionable story, instead of citing primary sources, be

skeptical. Ideally, the reporting would come from an official

channel or independently confirmed by multiple publications.

Still, the experts all agree: Verifying information yourself

isn't necessarily useful. Independent fact-checking websites do the

digging for you. PolitiFact's dedicated coronavirus hub is updated

with the most-shared information on the web. Each fact-check is

graded on its level of truthfulness and includes the sources

PolitiFact's reporters used to determine its veracity. The Federal

Communications Commission has a Covid-19 consumer warning website

that includes samples of robocall and text messages scams.

If someone does send you false information, be gentle. When

confronting That Person (you know who I'm talking about) in your

group chat, don't harshly correct them. "People shut down when you

do that or get angry," said Ms. Holan. She advised meeting them

where they are: "People are most sympathetic to outlets they like

and what they perceive to be their team."

Try sending someone corrective information from an outlet they

trust. If that's not available, there are always official sources

like the CDC. Google's advanced search can help with this. You can

narrow results for a query to a particular domain, like

"cdc.gov."

If you're stressed by the digital deluge, turn it off. If you

want to stay connected with official updates, there's a great

alternative to Twitter and TV: Sign up for your city's Covid-19

text alerts where available. San Francisco, Chicago, Seattle and

New York are among those that have a system in place.

Yep, you can mute it all -- the group texts, Twitter accounts,

Facebook friends, email and Slack. (Just don't ignore your boss!)

There is a lot of fear and uncertainty in this moment. Please take

care of yourself in all the ways you need, even if that means

virtually shutting up your uncle.

--For more WSJ Technology analysis, reviews, advice and

headlines,

sign up for our weekly newsletter

.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 22, 2020 09:14 ET (13:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

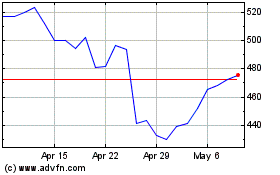

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024