By Richard Rubin and Rachel Louise Ensign

President Biden's American Families Plan would raise

capital-gains taxes and end a rule that has been a cornerstone of

estate planning for generations of wealthy Americans.

The change -- increasing the top capital-gains rate to 43.4%

from 23.8% and taxing assets as if sold when someone dies -- would

upend the tax strategies of the very richest households. Mr.

Biden's plan would also claw back some benefits Congress gave to

slightly less wealthy multimillionaires who have been spared from

the estate tax but now could face capital-gains taxes at death.

Today, people who own assets that have boomed in value -- Apple

Inc. stock, the family beach house, a three-generation

manufacturing company -- don't pay capital-gains taxes unless they

sell. Under the Biden proposal, those unrealized gains would

trigger taxes upon the owner's death, minus a $1 million per-person

exemption.

More than two-thirds of all U.S. families have some unrealized

capital gains, according to the Federal Reserve, but most would be

covered by the $1 million exemption. For families in the top 10%,

with a median net worth of $2.6 million, median unrealized gains

are $519,000.

The plan likely will change as it moves through Congress, and

some Senate Democrats are already balking. Rep. Cindy Axne (D.,

Iowa) is concerned about the impact on family-owned farms and is

working with other lawmakers from rural areas to seek an exemption

for them. Republicans say tax increases would kill jobs and slow

the economic recovery.

Meanwhile, wealthy people and their advisers are rethinking

strategies and investments. Financial adviser Ken Van Leeuwen says

he has received more fearful calls from clients about the tax-law

changes in the past week than ever. Even those who voted for Mr.

Biden are worried. "Are we becoming socialists?" he said one asked

him.

Mr. Van Leeuwen's Princeton, N.J.-based firm caters to people

with net worth between $5 million and $25 million. Many are

concerned their children will pay taxes on inherited second

homes.

The Biden proposal would blow up several longstanding tax

concepts: That capital gains deserve a lower tax rate than wages

and that people can inherit old assets without paying capital-gains

taxes. Democrats and their allies say those features of the tax

system, however, are unfairly tilted to the very wealthy.

"It's one of the biggest, most inefficient and

hardest-to-justify tax breaks that exists in the code," said

Chye-Ching Huang, executive director of New York University's Tax

Law Center. "There's just a tiny, tiny sliver of people that have

that kind of gain. It's just so unusual."

Under the current tax system, the top capital-gains tax rate is

23.8%, compared with 40.8% on wages, with state taxes on top of

both. Congress created the lower rate as an incentive to invest and

a way to prevent the tax code from discouraging asset sales. It is

also a rough adjustment for inflation.

Heirs have to pay such taxes only when they sell and only on the

gain since the prior owner's death. The provision is known as the

tax-free step-up in basis and has been part of the tax code since

the Revenue Act of 1921. It saves taxpayers more than $40 billion a

year, according to the congressional Joint Committee on Taxation;

the Biden proposal would take back some of that.

The step-up in basis is separate from the estate tax, which is

based on net worth at death, not just appreciated gains. It has an

$11.7 million per-person exemption. Opponents of Mr. Biden's plan

warn of steep combined rates on people hit by both taxes.

"If we lose the step-up in basis, that turns the estate planning

world upside down," said Alvina Lo, a tax attorney and chief wealth

strategist at M & T Bank Corp. unit Wilmington Trust.

The problem, Democrats say, is that significant amounts of

income escape the income tax entirely, because people can buy

assets, borrow against them for living expenses and die without

paying income taxes on the gain. For very wealthy investors or

billionaire founders of companies who take small salaries as their

stock grows, it can make the income tax effectively optional.

"If you're elderly and own highly appreciated assets, God forbid

you should sell them while you're alive," said Lawrence Zelenak, a

Duke University law professor.

Under the Biden plan, except for charitable bequests, death is

treated like a sale, with a $1 million per-person exemption. He

would keep existing exclusions for gain on a principal residence of

$250,000 for individuals and $500,000 for married couples.

Now, someone who paid $2 million for a business and dies when it

is worth $12 million would pay no capital-gains taxes. And if that

is his only asset, he would owe no estate taxes. Under the Biden

plan, he would pay taxes on $9 million -- the $10 million gain

minus the $1 million exemption -- with a top marginal tax rate of

43.4%. Assets held in retirement accounts generally aren't

affected.

The capital-gains rate change and taxation at death work

together. Without the change to the basis rules, the 43.4% tax rate

would lose money for the government because it would encourage

people to hold assets that they would otherwise sell.

The Biden proposal says it will have unspecified "protections"

so family-owned businesses and farms won't owe taxes if heirs

continue to run the business.

Manufacturers and farmers, who tend to be more asset-rich and

cash-poor, are watching closely for those details, concerned they

might have to sell illiquid businesses to pay the taxes.

Courtney Silver, president of Ketchie Inc., a family-owned,

25-employee machine shop in Concord, N.C. that started in 1947,

said she was concerned about the potential impact.

"I really can't imagine being hit with that decision of that

potential tax implication," said Ms. Silver, 40 years old, who took

over the business when her husband, Bobby Ketchie, died in 2014.

"That to me is really hard to wrap my head around."

It could be challenging for asset owners to figure out their tax

basis, which is what they paid for the property and invested in it.

That complexity is part of what doomed a similar proposal in the

late 1970s, which Congress passed, then delayed, then repealed.

Others might sell long-held assets to pay the taxes.

Vera Dunn lives in Beverly Hills, Calif., with her 102-year-old

mother in a house bought for about $100,000 in 1965. Ms. Dunn

estimates the house would be worth $10 million to a buyer who would

tear it down.

She said she has borrowed $4 million against the house to pay

for her mother's care and is already concerned about California tax

changes on inherited property. If her mother lives past the

effective date of the Biden plan, Ms. Dunn said, it would be

impossible to pay the taxes and keep the house.

"It happens to be a beautiful house in a beautiful location. It

happens to be all I have," she said. "Nobody's going to cry over my

situation. I'm not passing a handkerchief around, but everyone I

think can relate to [it.] How do you feel if you can't keep the

family home and if businesses are not paying taxes that are worth

billions of dollars?"

Wealthy Americans with over $100 million in assets are already

turning to a range of techniques to minimize the hit from steeper

taxes on their wealth, and many have already shifted further into

tax-advantaged assets, said Mike Kosnitzky, co-head of the private

wealth practice at law firm Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman

LLP.

The Biden proposal would make it be tougher for the merely

wealthy who use less sophisticated tax-planning vehicles to avoid a

hit, Mr. Kosnitzky said.

Jeremiah Barlow, head of family wealth services at Mercer

Advisors Inc., says his clients, who typically have a net worth

between $5 million and $15 million, are giving assets to loved ones

before they die to take advantage of the estate-and-gift tax

exemption.

Mr. Barlow is telling them they should be ready to accelerate

asset sales if the proposed changes take effect and to monitor the

effective date set by Congress. A family may want to sell its

business before the end of the year or sell stock that has

appreciated in value if they already planned to sell those assets

in the next few years regardless of tax-law changes.

Donating appreciated assets to charity could become an

increasingly appealing way of minimizing a tax bite, said Michael

Nathanson, chief executive of Boston financial advisory firm The

Colony Group. Such donations can bypass capital-gains taxes, and

the deductions from them can be used against other income.

One strategy to contend with the proposed tax-policy change tax

is to simply wait it out.

Republicans' opposition could make the tax change fragile. If

the plan were permanent, asset owners would face a roughly

tax-neutral choice -- pay taxes on a sale now or at death later.

But given the political landscape, the choice may be to sell now or

hang on until a future Congress changes the rules.

Investors' expectations are crucial for the policy change to

work as intended, said Jason Furman, who was a top adviser to

former President Barack Obama.

"If you think that it's going to be repealed by the next

Republican administration and the repeal is going to stand, then

you might still not realize your gains," he said. "It will take

some time to survive one regime change, to become an expected part

of the law."

Write to Richard Rubin at richard.rubin@wsj.com and Rachel

Louise Ensign at rachel.ensign@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 29, 2021 13:22 ET (17:22 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2021 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

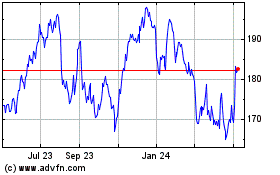

Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

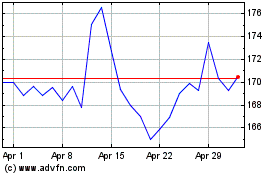

Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024