A Decade of U.S. Market Exceptionalism Probably Won't Repeat -- Journal Report

December 17 2019 - 9:20PM

Dow Jones News

By James Mackintosh

Rank the performance of stock markets over the past decade and,

in rough approximation, these are the results: U.S. first,

everywhere else way behind.

Bears often argue that U.S. market exceptionalism is a bubble,

especially with valuations as high as they are.

However, the primary reason for the outperformance of U.S.

stocks is that America itself has performed far better this decade

than other places. Its economy has beaten those of most other

developed countries. Its companies have led in new disruptive

technologies. It has avoided the crises that have hit Europe and

many emerging markets. It fixed its banks after the recession more

quickly than Europe. And -- perhaps thanks to a lack of antitrust

enforcement -- earnings have soared, even as the dollar has done

well.

Fundamentals matter, and America's fundamentals have just been

stronger.

Yet there are two reasons to doubt the sustainability of this

outperformance. The first is that performance tends to go in

cycles, as governments shift policy, companies rise and fall, and

technologies develop (remember that the standard mobile phone of

the 2000s was designed in Finland, not California).

The great decade for the U.S. followed a terrible decade in the

2000s, when U.S. stocks lost money even with dividends reinvested,

and beat only Japan among large markets. Over the past two decades

together, the U.S. sits in the middle of the pack of significant

markets, ahead of Japan, the U.K. and eurozone, but behind Canada,

Australia, Sweden, Switzerland and emerging markets. (Throughout

this article performance is considered in dollar terms including

dividends.)

Second, it's historically rare for richly valued markets to hold

on to their valuation premium over many years, and the U.S. --

thanks to a handful of very large technology companies such as

Apple, Amazon, Facebook and Alphabet -- is richly valued compared

with the rest of the world. If the next decade is a repeat of the

one now ending, maybe the U.S. can stay ahead.

But the next 10 years are likely to bring big changes, political

turmoil, new technologies and a shift from reliance on monetary

policy -- which is hobbled by low interest rates -- to a bigger

role for government stimulus in determining market direction. Not

only does the U.S. have to weather these changes better than other

markets, it has to do so by enough to justify retaining its premium

valuation.

The real drivers of the U.S. lead are the massive outperformance

of economically sensitive cyclical sectors such as industrials,

consumer discretionary and financials; the predominance of tech

companies within the U.S. market; and the strong dollar over the

decade.

The dollar started out the decade badly, falling in 2011 to its

weakest against trading partners in modern history amid fears that

a debt-ceiling standoff between the White House and Congress could

lead to a default. In the end there was no default, but the loss of

the government's coveted triple-A credit rating that August marked

the low point for the currency. The stronger economy and trouble

elsewhere helped the dollar rebound more than 33% since then,

putting it above its average exchange rate since 1970, according to

JPMorgan Chase's inflation-adjusted trade-weighted currency

index.

Fundamentals drove investors to buy the U.S., but American

stocks did far better than the performance of the U.S. economy or

even global earnings of U.S. companies would justify on their own.

It is at least doubtful that such a performance can be

repeated.

Three things happened. American companies increased profits from

abroad in a spectacular way, helping S&P 500 profit margins to

a record last year even as corporate profit margins within the U.S.

slumped from their 2012 peak to below where they stood at the end

of 2009. With politicians turning against globalization, low-tax

countries under pressure and foreign regulators turning their

attention to the high profits made by some of the largest U.S.

companies, simply maintaining margins would be a positive

outcome.

Big tax cuts boosted earnings, something unlikely to happen

again given how low U.S. corporate taxes now are.

And valuations soared. At the start of 2010 the U.S. market was

valued at 14.5 times expected operating earnings over the next 12

months, according to I/B/E/S Estimates. That has now jumped to

almost 18 times, valuing the U.S. market much more highly than the

eurozone, U.K., Japan or emerging markets. The rise in valuation in

the U.S. was also far bigger than elsewhere (forward

price-to-earnings ratios for Japan and emerging markets fell over

the decade). Price-to-book multiples in the U.S. have also

jumped.

If the S&P valuation rose by the same amount again, it would

take the forward P/E ratio to 21, a level reached in data since

1985 only during the dot-com mania of the late 1990s. It's not

impossible, but it would require a big bubble, something that

doesn't happen often.

Of course, if the next decade brings more natural disasters,

political unrest and currency crises, the U.S. may well benefit

from its relative stability. Even then, it would be foolish to

expect a repeat of the wonderful bull market of the past

decade.

Mr. Mackintosh writes The Wall Street Journal's Streetwise

column. He can be reached at james.mackintosh@wsj.com.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

December 17, 2019 21:05 ET (02:05 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

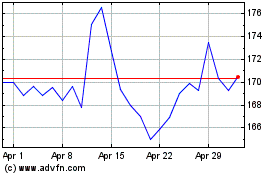

Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

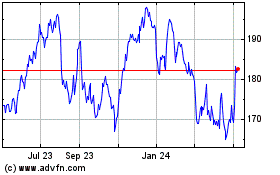

Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024