By Patience Haggin

For Gap Inc., January 2020 will bring a lot more than just

after-Christmas sales.

Starting next year, all California residents will have the right

to ask retailers, restaurants, airlines, banks and many other

companies to provide them with any personal information they may

have, including individual contact information, purchases and

loyalty-program history. Consumers also can ask that businesses

delete their information, or opt out of letting it be sold.

"You have to find a way to capture all that information and

track it so you know what's happening with that information," said

Dan Koslofsky, associate general counsel for privacy and data

security at Gap. "And that's a pretty significant undertaking for

most companies. Unless you've been in a regulated space like health

care or financial services, you probably haven't done that

previously."

The California Consumer Privacy Act was designed to make

data-trafficking companies and tech giants such as Amazon.com Inc.,

Alphabet Inc.'s Google and Facebook Inc. more transparent about how

they handle user data.

But the law, which passed last year and goes into effect Jan. 1,

applies to any for-profit business that does business in California

and collects data on California residents, as long as its annual

revenue tops $25 million, or it holds personal information on at

least 50,000 consumers, or it generates at least 50% of its annual

revenue from selling user data. Even companies with no physical

presence in California but a website that serves Californians are

preparing to comply.

Some 500,000 U.S. businesses across all sorts of industries meet

that criteria, according to the International Association of

Privacy Professionals. They include companies as varied as

Starbucks Corp. and Gap, health insurer Aetna Inc.,

financial-services firm Wells Fargo & Co., American Airlines

Group Inc. and toy maker Mattel Inc. -- as well as hundreds of

thousands of small and medium-size businesses.

Few companies keep all their customer data in one place, and now

many are scrambling to build tools to match up individuals' data

across disparate systems, such as directories, purchase histories

and customer-service request logs. Companies also have to review

their data-sharing arrangements with vendors and disclose them in

their terms of service.

Gap had a certain head start because it already brought its

European business into compliance with the European Union's General

Data Protection Regulation, which took effect last year and has

similar customer-data requirements. To prepare for these laws,

Gap's privacy team interviewed about 200 employees across the

company about how they use data.

Many other companies, though, are much further behind. The

California law was passed last summer, but many companies delayed

preparations during the lengthy amendment process. In a survey

PricewaterhouseCoopers conducted last year, only 52% of respondents

said they expected their company to be CCPA-compliant by January

2020.

"I'm concerned about people falsely accusing us of having

information on them when indeed we don't," said Jeff Savage,

president of the River Cats, Sacramento's minor league baseball

team, which has more than 100,000 people in its email database.

"How do I prove to Joe Smith that I don't have his info?"

Once the law becomes enforceable, which is expected by next

summer, businesses that get a customer data request will have to

comply within 45 days or risk pricey fines and possible civil

litigation. The law threatens steep damages in the event of a data

breach -- as high as $7,500 per affected person. Businesses also

have to add a "do not sell my personal information" option to their

home page where consumers can opt out.

Given the difficulty of maintaining a separate protocol for

California's 39.6 million residents, many businesses are choosing

to apply the changes they make for California to the rest of the

country. Some anticipate that the California law will become a kind

of de facto national standard, much like the state's standards for

auto emissions.

Rena Mears, a principal with the law firm DLA Piper, said, "99%

of the businesses that we're dealing with are choosing to make the

law apply to all their U.S. customers."

The requirements' complexity has created an opportunity for some

tech firms. Microsoft Corp. is preparing compliance software, as is

LiveRamp Holdings Inc., as well as startups like SECURITI Inc.,

Text IQ Inc. and BigID Inc.

Gap said it doesn't sell data to brokers but does share customer

mailing addresses with catalog companies. The retailer's privacy

team has been scrutinizing those contracts and its disclosures to

customers to make sure they comply with the California law.

One uncertainty is whether retail loyalty programs -- which

reward consumers who let a company keep and sometimes sell their

data -- could be considered a form of discrimination against

shoppers who exercise their data rights. Another question is

whether a customer who used a credit card in a store but never

provided further data would be owed a personal data file. Mr.

Koslofsky said Gap wouldn't store enough data on such a user to be

able to identify them and would explain that in response to such a

request.

Companies are gearing up for every conceivable scenario,

including the possibility that identity thieves may pose as someone

else to obtain their data.

If consumers in large numbers opt out of data sales, the

greatest impact may be on data vendors and digital-advertising

companies.

Los Angeles-based Factual Inc. provides location-tracking

software for mobile apps, and then sells the users' location data

to advertisers. If a user allows the app to use his or her location

but opts out of having the data sold, Factual would still be

obligated to provide the service but wouldn't be able to include

that individual's data in the segments it sells to ad buyers,

Factual's Chief Marketing Officer Brian Czarny said.

The California state legislature passed the hastily written law

in a deal to block a more ambitious ballot initiative. That left

the door open for both industry and privacy groups to spend the

past year wrangling over amendments to the law, rather than

preparing for it.

The bills for software and attorneys can creep up.

"Any Fortune 500 company is going to spend at least $1 million

on CCPA compliance" in the law's first year, said Jay Cline, a

principal with PricewaterhouseCoopers. "And we've seen budgets as

high as $100 million."

Write to Patience Haggin at patience.haggin@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 08, 2019 09:14 ET (13:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

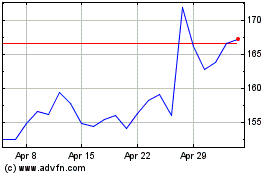

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOGL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

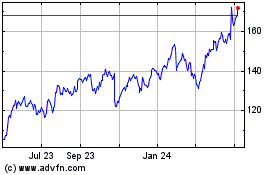

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOGL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024