By Brent Kendall and Ryan Tracy

WASHINGTON -- Lina Khan, a progressive champion nominated by

President Biden for a key enforcement post, wants to transform

antitrust policy into a bulwark against corporate power by blocking

more mergers, attacking monopolistic practices and potentially

breaking up some of America's largest companies.

Ms. Khan, 32 years old, is awaiting Senate confirmation for a

Democratic seat on the five-member Federal Trade Commission after

she was cleared by the Senate Commerce Committee. She has risen to

prominence -- and gained bipartisan support -- as Democrats and

Republicans alike have said lax antitrust enforcement, especially

in the tech sector, has allowed dominant firms to hobble rivals and

stifle competition.

Her targets have included not just Big Tech but also Big

Chocolate and others. She has argued for hawkish positions that

would overhaul legal doctrine and go well beyond the approach of

recent antitrust enforcers. While her most ardent supporters

believe such changes are long overdue, her views have prompted a

debate on whether her approach is realistic and potentially so

sweeping that it could prove jarring to the economy.

"Stepped-up antitrust enforcement is one thing," said Howard

University law professor Andrew Gavil, who was a top FTC staffer

the last time Democrats controlled the commission. "Changing the

standards is a different matter," he said.

Mr. Gavil, who favors more enforcement, said Ms. Khan will have

to consider how to translate her views into something that can be

applied in practice. "That's more challenging than simply being a

critic on the outside," he said.

If confirmed, Ms. Khan, a professor at Columbia Law School,

would join an agency that enforces antitrust and

consumer-protection laws across the economy. She would further

cement the rise of a progressive camp that believes the U.S. faces

what she has described as "a sweeping market power problem" in

which large firms have been allowed to become too dominant.

"Lina has been very clear-eyed in recognizing that the core

questions have to do with power, with the ability of private

entities to coerce and to bully," said Stacy Mitchell, co-director

of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, a research and advocacy

group.

A London-born immigrant who came to the U.S. at age 11, Ms. Khan

is soft-spoken and a prolific writer. During her teenage years in

the New York City area, she worked on the student newspaper at

Mamaroneck High School. She gained prominence through her criticism

of Amazon.com Inc., writing a widely read law-review article while

a student at Yale Law School that argued that antitrust law has

failed to restrain the online retailer.

Ms. Khan has rocketed through the progressive ranks, sounding

the alarm on corporate concentration in industries ranging from

airlines to agriculture. "Big chocolate is about to get even

bigger," she wrote in a 2013 article criticizing consolidation in

the world market for cocoa processing.

People close to Ms. Khan said she sees herself as an

intellectual leader in an antimonopoly movement, one that views

unchecked corporate power as a threat to democracy.

She was a House staffer on a congressional antitrust panel that

conducted a 16-month investigation of large online platforms and

last year recommended that lawmakers take steps to rein them in.

She served as legal director of the Open Markets Institute, a group

that favors aggressive trustbusting.

Ms. Khan, who declined to comment, would join an FTC that

scrutinizes mergers and business practices to determine whether

they illegally suppress competition in the marketplace. She has

argued that the current framework for enforcing U.S. antitrust laws

is misguided because it favors corporate efficiency and short-term

consumer welfare interests -- a preference for Amazon's prices and

convenience, for example -- over maintaining a competitive

structure in which a healthy number of rival firms keep one another

in check.

The current system, she has said, essentially gives a green

light to most corporate mergers and all except the most

questionable business practices.

Restoring vigorous enforcement "first requires recognizing that

the source of the problem is not just a lack of enforcement, but

also the current philosophy of antitrust," Ms. Khan wrote for the

Yale Law Journal in 2018.

Democrats have embraced Ms. Khan's arguments that enforcement

has been inadequate, supporting tougher action by the FTC and the

Justice Department, as well as legislation to strengthen antitrust

laws. Some, however, have said the FTC can change its approach

without embracing Ms. Khan's philosophical shift away from how

enforcers have thought about the law for decades.

Republicans are more reserved on potential legislative changes

and have been critical of Ms. Khan's central argument that

antitrust policy should focus on more than just consumer welfare.

Some have worried that her views would lead to burdensome

government interference across industries, even as they support her

positions against Big Tech.

Sen. Mike Lee (R., Utah), the top Republican on a Senate

antitrust panel, voted against Ms. Khan in the Senate Commerce

Committee and said liberal changes aren't needed. "Our laws could

meet the need if only enforcers brought the appropriate facts and

the appropriate evidence," he said during her April confirmation

hearing.

He asked if Ms. Khan would have to recuse herself from Big Tech

cases because of her work on the House online-platform

investigation. The FTC is currently investigating Amazon.

Ms. Khan said she would consult with FTC ethics officials if

recusal questions arose.

Concern about tech dominance has allowed Ms. Khan to forge

common ground with some Republicans by arguing that concentrated

corporate power is a threat to liberty. Sen. Ted Cruz (R., Texas),

himself a former FTC staffer, said at the hearing that the FTC

"should be doing much more" on Big Tech and that he looked forward

to working with her.

The House antitrust report concluded that Amazon, Apple Inc.,

Alphabet Inc.'s Google and Facebook Inc. wield monopoly power --

and criticized U.S. antitrust enforcement agencies as failing to

curb their dominance.

All four companies disputed the committee report's findings and

declined to comment on Ms. Khan's nomination.

Carl Szabo, general counsel at NetChoice, an industry group

whose members include Amazon, Google and Facebook, said Ms. Khan's

views "could throw into question American innovation, economic

exceptionalism, and consumer happiness for decades to come."

Ms. Khan has acknowledged that some markets, particularly in the

digital space, might naturally be dominated by a handful of online

firms because of their size and scale. In those circumstances, she

has argued, the government should consider placing structural

limits on the lines of business in which a firm can engage, or

perhaps regulate online platforms directly as "common carriers" as

it does with public utilities.

While Ms. Khan has extensively criticized the status quo, she

has been less specific on what, realistically, can be done

differently, especially as conservative court rulings have narrowed

antitrust laws in a direction favorable to business for

decades.

She could find herself with allies at the FTC to test the

waters.

Democrat Rebecca Kelly Slaughter, the agency's acting

chairwoman, has staked out aggressive enforcement positions during

her three years on the commission, urging a tougher stance on

mergers and recently creating an internal group that could help

implement first-ever regulations that prohibit certain kinds of

business practices as unfair methods of competition.

"Lina's work has substantially advanced the public debate on

competition, and I am not aware of any places she and I disagree,"

Ms. Slaughter said.

The FTC's makeup is still taking shape. Mr. Biden has yet to

designate a permanent chair, and he will have another opening if

Commissioner Rohit Chopra, a progressive, is confirmed to run the

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

An aggressive FTC could face several legal battles in the near

term. A fight could ensue if Democrats assert the power to issue

competition regulations, an authority that is in dispute. Early

targets could include noncompete clauses in employment contracts

and pharmaceutical settlements that potentially delay the entry of

generic drugs.

The commission might face tough decisions on whether to bring

lawsuits on mergers or monopolization because losses in court can

set precedent for future cases. In recent years courts rejected

government antitrust claims against the chip maker Qualcomm Inc.

and American Express Co.

Ms. Khan's supporters have said it is worth the risk. If the FTC

runs into skeptical judges, "the cases can help clarify where

Congress needs to step in," said Fordham University law professor

Zephyr Teachout. "If you don't bring the cases, you are not going

to win them."

Write to Brent Kendall at brent.kendall@wsj.com and Ryan Tracy

at ryan.tracy@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 23, 2021 12:14 ET (16:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2021 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

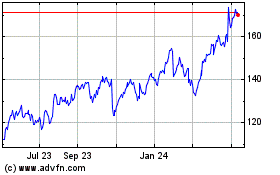

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOG)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

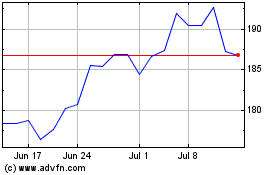

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOG)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024