Introduction

Crypto-assets have drawn much attention of late. From

https://www.forbes.com/sites/rhockett/2017/12/17/betting-on-beta-coin/#20a9cc364670"

href="https://www.forbes.com/sites/rhockett/2017/12/17/betting-on-beta-coin/#20a9cc364670"

target="_self">Bitcoin’s market volatility through

https://cointelegraph.com/news/coinbase-reportedly-secures-20-billion-hedge-fund-through-its-prime-brokerage-services"

href="https://cointelegraph.com/news/coinbase-reportedly-secures-20-billion-hedge-fund-through-its-prime-brokerage-services"

rel="nofollow noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">regulator

puzzlement over how best to regulate Bitcoin’s cousins, stories in

the financial press seem as often as not to concern digital

currencies, blockchain technology, or any of a bewildering array of

newish topics now routinely lumped together under the barbarous

rubric of

‘https://ftalphaville.ft.com/2017/08/18/2192493/the-finance-franchise-and-fintech-part-2/"

href="https://ftalphaville.ft.com/2017/08/18/2192493/the-finance-franchise-and-fintech-part-2/"

rel="nofollow noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">fintech.’

Against this backdrop one hears

https://www.businessinsider.com/hedge-funds-being-lured-by-coinbase"

href="https://www.businessinsider.com/hedge-funds-being-lured-by-coinbase"

rel="nofollow noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">countless

dark and countless sunny augurs. Some claim that crypto-monies will

supplant ‘fiat’ money, thereby liberating us all from both

government oppression and central bank ‘debasement’ of currencies.

Others warn blockchain will aggravate crime and yet-further shade

shadow-markets, which we’ll lose all capacity to regulate. And

still others look forward to privacy utopias and revived

https://www.forbes.com/sites/katiegilbert/2014/09/22/why-local-currencies-could-be-on-the-rise-in-the-u-s-and-why-it-matters/#4f627dc44e95"

href="https://www.forbes.com/sites/katiegilbert/2014/09/22/why-local-currencies-could-be-on-the-rise-in-the-u-s-and-why-it-matters/#4f627dc44e95"

target="_self">local ‘circulation economies.’

Many a layperson who’s lacking in info-tech education might

wonder now just what to make of these claims. Must one be a

programmer or cryptographer before s/he can weigh-in on such heady

matters?

I think the answer where most fintech’s concerned is a ‘probably

not.’ Where crypto-currency’s the subject,

however, I’m sure that the answer is no. For as

it happens, we have been here before.

The story of America’s money is a preview of the story we’ll

soon see unfold for crypto-money. Our money’s past is, in short,

our cryptos’ future.

Dollar bills are remarkable things. They’re the same all over

the United States. Take out money from a bank branch or an ATM

anywhere and you’ll get the same thing for your trouble: a

combination of green one dollar, five dollar, ten dollar, twenty

dollar or perhaps hundred dollar notes. They’ll all look the same,

and they all will be worth the same when their denominations are

the same.

That is what sovereign-issued currency looks like, even when

paid out by nominally ‘private’ banks. Because they all deal in

national currencies, banks are not really as private as you might

think. They are licensed by us, the sovereign public, to deal in

our money –

http://dollarsandsense.org/archives/2018/0318hockett.html"

href="http://dollarsandsense.org/archives/2018/0318hockett.html"

rel="nofollow noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">our Federal

Reserve Notes, as our money bills call themselves.

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2820176"

href="https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2820176"

rel="nofollow noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">In effect,

banks are franchisees, while we the sovereign public are the

franchisor and our national money is the franchised good.

You can think of the uniform value and appearance of our

currency as being a bit like those golden arches you see all around

if you like: They serve to let everyone know that the item’s the

same irrespective of just where you are in our nation – New York,

California; Florida, Alaska ... They are always and everywhere the

same.

And if a bank abuses the brand by, say, issuing bad loans or

over-levering itself, it will risk losing its charter much as a

restaurateur who sells spoiled food risks being booted from the

franchise. That’s how franchises work. They are ‘quality control’

pacts, with the franchisees abiding by the terms and the franchisor

administering the terms. Where our money’s concerned,

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2820176"

href="https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2820176"

rel="nofollow noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">we are the

franchisor.

You might be tempted to think things have always been thus.

Didn’t the U.S. make the dollar its money right from the start?

The answer is, ‘yes and no.’ The key feature of the dollar in

the early days of our republic – until 1863 – is that it was then a

mere unit of account, not a currency. Sure, the Mint minted coins,

but paper money – ‘notes’ – were issued by private banking

institutions. Hence the term

‘http://dollarsandsense.org/archives/2018/0318hockett.html"

href="http://dollarsandsense.org/archives/2018/0318hockett.html"

rel="nofollow noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">bank notes’

for paper currencies that circulated in the 19th

century. America’s paper money supply was a plethora of privately

issued ‘bank notes.’

Bank notes were denominated in dollar increments, but were not

sovereign-issued liabilities. The banks were their own franchisors

and franchisees alike, and their notes were their own liabilities -

liabilities of their private issuers. Different issuers, for their

part, were differently reliable. Two banks might both promise

redeemability of their notes into the same quantum of something

more solid – gold, for example – but might well be differently able

to live up to their promises.

These differences among banks’ reliability stemmed from a

variety of factors. One was that bank regulation was more

technologically difficult in the 19th century, meaning

that regulators could be only so effective at exercising ‘quality

control’ over paper currency issuers. Another was that all banks

were chartered and regulated by states rather than by our federal

government, meaning that differing state competencies at regulating

could bring differing values to currencies issued in different

states.

The upshot of this ‘https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qdR4ujneQzo"

href="https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qdR4ujneQzo" rel="nofollow

noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">Banking Babel,’ as I call

it, is that the nation’s currency supply consisted in thousands of

distinct bank notes all trading at various discounts to stated par.

A dollar note issued by Billy the Kid Bank or Sidewinder Bank might

trade at 50% of par, for example, amounting to no more than ‘four

bits,’ not a dollar. A dollar note issued by Wyatt Erp Bank or Bald

Eagle Bank might, by contrast, go for 90% of par, or even full

par.

Making things worse, these currencies constantly fluctuated in

value, both in relation to the goods and services they could

command and in relation to one another.

‘How much money’ you had in your pocket thus varied with whose

notes you carried and when, even though all were denominated as

dollars. Shopkeepers in consequence had to maintain regularly

updated discount schedules behind their counters, instructing

clerks how much to discount separate banks’ notes in determining

‘how much’ (of what) to charge buyers for goods.

If you carried multiple banks’ notes in your pockets, making

purchases at the general store could take you – and the store clerk

– much longer than we’re used to now. Imagine what queues would

form at the ‘checkout lines’ if we did that now…

Scarce wonder that this period of U.S. banking history is called

the ‘https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qdR4ujneQzo"

href="https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qdR4ujneQzo" rel="nofollow

noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">wildcat banking’ era.

(Those who think this was a good idea call it the ‘free banking’

era. It was free alright – it was pretty much value-free.)

Needless to say, private banknote money didn’t make for an

optimal payments system. It was good that the nation had a unit

of account – the dollar – but unfortunately it still lacked an

actual currency.

This all changed in 1863. By that point the nation was embroiled

in civil war. The Civil War threw up two factors that made a

uniform national currency possible. The first factor was that the

stresses of war made a single and stable currency more clearly

necessary than ever before. To prosecute the war the federal

government had to be able to spend its own currency anywhere in the

union where government operations were necessary. The second factor

was that the southern slave states, which had always been the

principal objectors to national monetary uniformity, were

conveniently unrepresented in Congress during the war years – they

were trying to secede, after all.

The upshot was that Congress passed the

https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/national-bank-act-1863"

href="https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/national-bank-act-1863"

rel="nofollow noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">National Bank

Act, signed into law by President Lincoln in 1863. The Act

established, for the first time in our nation’s history, a system

of federally chartered ‘National Banks,’ located all over the

nation, all issuing the very same currency. The latter was named,

tellingly, the ‘Greenback.’ Sound familiar?

The National Bank Act (‘NBA’) transformed our interlinked

banking, financial, and monetary systems. In very short order there

were federally chartered banks in every state of the Union, all of

them subject to uniform regulatory standards and all of them

issuing, accordingly, a uniform currency with a uniform value.

These banks could also sell U.S. Treasury securities, making of

them a system of outlets for issuance of both of our federal

government’s principal circulating liabilities – Greenbacks and

T-Bills. In no time at all, ‘wildcat’ banknotes left circulation,

with Greenbacks and T-bills – our two sovereign financial

instruments – the proverbial ‘only game in town.’

The administrator of this national bank system was called,

tellingly, the https://www.occ.treas.gov/"

href="https://www.occ.treas.gov/" rel="nofollow noopener

noreferrer" target="_blank">Office of the Comptroller of the

Currency, or ‘OCC.’ The name is telling because ‘comptroller’ is

merely archaic English for ‘controller.’ The OCC, housed in

Treasury, was the ‘controller’ – the administrator – of our first

truly national currency system. That, and only that, was why the

OCC was founded as the nation’s first federal bank regulator.

The OCC remains to this day one of our principal federal bank

regulators. It is the chartering authority for national banks,

administers those banks’ portfolio-regulatory and other regimes,

and has final word on whether a national bank has gone bankrupt. It

has rather less to do with the national currency, however, than it

had for its first fifty years.

That is because, by 1913, we as a nation had come to realize

that a healthy economy needed more than a uniform

currency. It also needed what is known in the discipline

as an elastic currency.

An elastic currency is a currency whose supply can be adjusted

to accommodate, while not over-accommodating, transaction

demand. The idea is to maintain just enough money supply to

accommodate desired transaction volumes, so as not needlessly to

squelch desired transacting, while at the same time preventing

over-issuance of the sort that can spark inflation – the classic

problem of ‘too much money’ chasing ‘too few goods.’

The OCC and Treasury more generally were not well equipped,

operationally or transaction-technologically speaking, to engage in

what I elsewhere call the daily ‘money-modulatory’ task that an

elastic currency requires. Central banks of the kind found all over

the ‘developed’ world circa 1913, by contrast, were well suited to

the task. The U.S. accordingly established its version of a central

bank, patterned partly on European models and partly on private

clearinghouse arrangements among banks, with the Federal Reserve

Act of 1913.

The https://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/fract.htm"

href="https://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/fract.htm"

rel="nofollow noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">Federal

Reserve Act (‘FRA’) established the Fed that we all know today, and

transferred administration of the national money supply from the

Comptroller to this new entity. This is why the ‘Greenbacks’ you

now find in your pocket call themselves, not ‘Treasury Notes,’ but

‘Federal Reserve Notes.’ So we now use ‘bank notes’ as currency

just as we did in the 19th century. It’s just that

they’re public bank notes – ‘central’ bank notes – rather

than private bank notes. They are Citizen Notes,

you might say.

Now, what has this to do with crypto?, you might be asking.

Well, think about it for a moment …

The Stages Go Digital

Let’s call the pre-NBA ‘wildcat banking’ era of wildly

fluctuating private currencies ‘Stage 1’ of American monetary

history. Let’s call the post-NBA, pre-FRA period of uniform but

imperfectly elastic national currency ‘Stage 2’ of American

monetary history. And let’s call the post-FRA period we’ve

inhabited over the past century ‘Stage 3’ of American monetary

history. Where might we situate digital currency development along

this phased sequence?

I think it’s perfectly obvious that we’re at Stage 1 where

digital currency’s concerned. We’re amidst, that’s to say, digital

currrency’s ‘wildcat’ era. For one thing, there are many such

currencies – indeed, a bewildering and seemingly all-the-time

growing array of them. For another thing, they are all of them

issued by private issuers, some of which seem to be more or less

reputable, others of which seem to be … well, not so much. And

finally, thanks to the factors just mentioned, these currencies

fluctuate wildly in value, both relative to what they can purchase

and relative to one another.

They’re essentially https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qdR4ujneQzo"

href="https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qdR4ujneQzo" rel="nofollow

noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">digital wildcat

banknotes.

This is of course not a sustainable future for crypto. Nothing

whose value is so wildly unstable can function for long as a

‘money.’ Something must change, then, before digital currency can

expect a future.

What, then, might change? What might a ‘digital Stage 2,’ then

‘digital Stage 3’ look like? It seems to me that here, too, the

future is obvious.

Note first that, unlike during the late 19th and

early 20th centuries, there is no reason that what I’ve

called ‘Stage 2’ and ‘Stage 3’ can’t be reached simultaneously. The

reason is that our nation came to see the necessity of a stable

currency before it came to see the necessity of an elastic

currency, and accordingly instituted those things pursuant to the

same ‘stage chronology’ of its own learning. Now, however, we’re

well familiar with both those necessities, and can accordingly move

to uniformity and elasticity in the digital currency space

simultaneously.

Next, note that the Fed, like other central banks worldwide, is

now looking to upgrade the national payments architecture, which it

administers. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Distributed_ledger"

href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Distributed_ledger"

rel="nofollow noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">Distributed

ledger technology (‘DLT’), which forms the backbone of the

better-known digital currencies, looks to be particularly promising

where such upgrading is concerned. Within the next several years, I

am wagering, payments systems worldwide will be built on

distributed ledgers. The U.S. will be late as we always are where

payments technology is concerned, but we’ll still soon be

there.

When we do, what do you suppose happens? Easy: The dollar

will go digital. The Fed will issue ‘Federal Reserve “Coins”’

and their keystroke equivalents much as it issues ‘Federal Reserve

“Notes”’ and their keystroke equivalents now. In this new world,

there will be little more use for what I’ll call ‘Wildcat Crypto’

than there was for ‘Wildcat Currency’ after the National Bank Act

of 1863. These ‘assets’ will simply fade out, retained only as

means of illicitly transacting in criminal activities until

caught.

This is true even of the

‘https://cointelegraph.com/news/report-stablecoins-see-significant-growth-in-adoption-over-recent-months"

href="https://cointelegraph.com/news/report-stablecoins-see-significant-growth-in-adoption-over-recent-months"

rel="nofollow noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">stablecoin’

products that have developed in recent months with a view to

addressing the wild fluctuations problem. Most of these peg to the

dollar. What need of that when the dollar itself soon goes

digital?

The Digital Dollar and a Citizens’

Fed

A Fed-issued and -administered digital dollar will be every bit

as uniform and elastic as the Fed-issued and administered

pre-digital dollar has been. Indeed it will likely be even more

easily managed thanks to the superior tracking ability afforded by

DLT. It will also, I predict, be something more: Because of the

speed, reliability, and tractability of distributed-ledger-tracked

credits and debits, a Fed-administered payment ledger will render

quite feasible something that would have been difficult until

recently: what I elsewhere call ‘Citizen Central Banking.’

That’s right, we shall soon be able to ‘cut out the banks’ as

proverbial ‘middlemen’ between our citizens and their central bank.

All citizens will be able to maintain what I call ‘Citizen

Accounts’ with the Fed. Not only will all citizens be ‘banked’ –

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2435534"

href="https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2435534"

rel="nofollow noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">no one

‘unbanked’ – in these circumstances, but the Fed will then have

more potent monetary policy instruments at its disposal as

well.

In the midst of recession or liquidity trap, for example, our

central bank will no longer need supply cheap money to private

banks and then hope they’ll lend it to ordinary citizens so’s to

prime the consumer spending pump. Instead it can credit our Citizen

Accounts directly. The

‘https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1987139"

href="https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1987139"

rel="nofollow noopener noreferrer" target="_blank">pushing on a

string problem’ that so plagued the Fed’s QE strategies in 2009-12

will be much diminished. By the same token, when spending appears

to be ‘overheating’ and inflationary pressures loom, the Fed can

simply offer or raise interest payments on Citizen Accounts.

Direct central banking, in short, is apt to be far more

effective even than indirect central banking has been. And the new

digital dollar – still Fed-issued, still Fed-administered – will

make that more feasible than it’s ever been.

Conclusion

There is of course much more to say about all of this, which I

do in more scholarly as well as technical policy-pushing and

program-designing work. But for present purposes the point should

be clear. Money’s past is always and everywhere money’s prologue.

All that changes is the technical base upon which our money systems

are founded.

Insofar as the state of the art now is DLT, money itself will be

DLT. But it still will be stable, and still will be elastic, if it

is money. And that means it still will be sovereign – it will be

‘our’ money.

So long, then, Bitcoin, and so long, Etherium. And welcome to

America, new Digital Dollar.

Source: Forbes

Robert Hockett Contributor

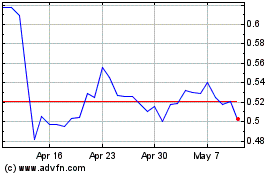

Ripple (COIN:XRPUSD)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

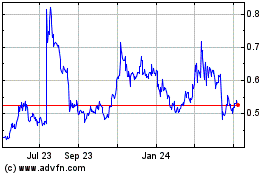

Ripple (COIN:XRPUSD)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024