By Thomas Gryta | Photographs by Whitney Curtis for The Wall Street Journal

David Farr looked down at the empty parking lot and blew up. It

was March 20, a cloudy day with a chill in the air. The coronavirus

and lockdowns were grinding the U.S. economy to a halt, sending

much of the American workforce home, including most of those at the

Ferguson, Mo., headquarters of Emerson Electric Co.

Mr. Farr, who had run the industrial conglomerate for two

decades, wasn't going anywhere. He told his assistant to summon the

other eight members of the OCE -- the Office of the Chief

Executive.

"We have a company to run," he growled, his voice echoing

through the empty sixth floor.

Mr. Farr wasn't naive. The virus had torn through China and

Europe, disrupting Emerson's operations. It was just a matter of

time before it spread in the U.S.

But World War II wasn't won by hiding, he liked to tell people,

and generals can't lead their armies from the bunker. He expected

employees to be present, and he wasn't going to run the company

from his home office.

"We have customers to serve and we can't frickin' do it if

nobody is here!" he bellowed to the group assembled in his

office.

Covid-19 has tested executives like few other events in modern

history. How they respond is making some careers and breaking

others.

In more than three dozen interviews throughout the course of the

year, Mr. Farr and his top lieutenants showed what it's like to

guide a global enterprise without a map.

The CEO reveled in his firm control and belief in constant

action. The pandemic rendered much of that experience

irrelevant.

It sprouted crises for Emerson's widespread global operations

faster than Mr. Farr could contain them. He butted up against the

reality of government regulations, suppliers struggling to meet

commitments and sick workers idling production.

For all his attention to detail, Mr. Farr knows he

underestimated the threat. "Why did we miss it?" Mr. Farr, 65 years

old, said last month. "I fault myself for that because I would have

been better prepared."

And yet he never stopped moving. Pushing through a crisis, with

small and reversible steps, and making tough choices, such as

pursuing an acquisition and pushing out a lieutenant, is better in

his mind than waiting to act.

"I might be wrong, but we get paid to make decisions and make

calls," he said in April after he shared financial projections with

Emerson's board of directors. "I would never jump off a cliff

without knowing a bit about what is at the bottom. But I know you

have to take jumps."

Seven charter planes

Emerson, with 90,000 employees around the globe, has roots in

the 19th century, when it made the first electric fans sold in the

U.S. Built up by acquisitions, it now produces cutting-edge systems

that automate factory processes, and heating and air-conditioning

equipment. It makes giant valves used in the oil industry as well

as Insinkerator garbage disposals and the red Ridgid pipe wrenches

used by generations of plumbers. It runs more than 200

manufacturing sites, with two-thirds of them outside the U.S. To

shareholders, it's a business worth $45 billion.

On Jan. 21, Mr. Farr was in Mumbai with five of his top

executives when he opened an email from the head of Emerson's China

business, Jennie Li. She wanted to talk about a virus outbreak --

and a possible government plan to lock down the sprawling city of

Wuhan.

The company employed 8,000 people in China at three dozen

facilities. Fewer than 1,000 people were infected by the virus

globally, and it was impossible to gauge where this would go.

Within days, China extended its Lunar New Year holiday to help

slow the spread of the virus. Mr. Farr finished his trip to India

and headed home, certain something big was brewing, even if its

extent was unclear.

Back in Ferguson, Mr. Farr asked his chief operating officer,

Steve Pelch, to put together a team to make sure they were doing

everything they could to keep the China operations safe and

running.

Mr. Farr knew that if China shut down, it could choke the

company and the global economy. Production would slow as parts

inventory thinned, orders would back up or be canceled and the loss

of scale and sales would make each transaction less profitable. The

resulting slowdown could reshape industries as companies shrank and

others -- those smart enough to be ready -- grabbed market

share.

Emerson's products were essential to keeping power and water

utilities and other critical services running smoothly, even

refrigeration for medicines and food. But now, a truck full of flow

meters coming from its Nanjing factory and going to Shanghai was

finding it almost impossible to get through.

The company reserved seven charter planes, ensuring it could get

its products out of the country for months to come. It proved to be

a lifeline when the cost of logistics skyrocketed.

This could all be managed, Mr. Farr thought. Seeing the Chinese

government deal with the virus early in the year and reopen without

major outbreaks gave him some confidence. "I got into a lot of

heated battles around here in St. Louis because I had the opinion

that you can live with this virus," he said.

On Feb. 4, Emerson reported first-quarter earnings. The

coronavirus was mentioned nine times by executives on the

conference call with Wall Street analysts. Mr. Farr expressed his

concern for the Emerson workers in China. He predicted that the

sales impact from virus disruption would be moderate but warned

economic growth could stall later in the year.

The company expected its Chinese factories to restart on Feb.

10, Mr. Farr told analysts and investors. The Chinese plants did

come quickly back on line. But Mr. Farr didn't anticipate what came

next.

'I'm too busy to die'

Mr. Farr is old school. He runs an industrial conglomerate.

He likes golf and the company jet. He likes a glass of wine, or

a vodka on the rocks, and goes on walks with his wife, Lelia,

almost every night through their upscale neighborhood of Ladue just

outside the city of St. Louis. He is up at 5:30 a.m. and tries to

stop working around 8 p.m., but is still quick to answer emails

later than that. He doesn't watch television outside the office and

spends most nights reading, lounging with Rocket and Doon, his two

King Charles spaniels, and going to bed early.

He grew up in Corning, N.Y., where his father was a math teacher

before becoming a plant manager at glassmaker Corning Inc. The job

moved the family to England, where his mother died from a cerebral

hemorrhage when Mr. Farr was 18.

Fresh out of business school, he joined Emerson in 1981 and rose

through the ranks working for a tough CEO who ran the place for 27

years with a focus on grinding down costs. Mr. Farr, too, is hard

on his managers. His shouting is balanced by an affinity for hugs,

handshakes and kisses. He dictates long memos to his secretary and

enjoys "good debates, bad debates and yelling debates."

He is politically conservative and an admirer of Jack Welch, the

hard-nosed former boss of General Electric Co. At an investor

conference in 2009, he said he wouldn't hire more U.S. workers

because the Obama administration was out to "fundamentally destroy"

manufacturing with its environmental and labor rules. He declares a

lack of interest in politics, yet he talks with the White House,

governors and mayors and makes sure people know it.

Emerson's salesman in chief rarely misses the chance to pitch

the company's products, even interrupting a conversation to tout a

Ridgid "closet auger," a device for unclogging toilets. He roots,

in jest, for heat waves, storms and flooding so Emerson can sell

more air conditioning compressors and wet/dry vacuums.

Mr. Farr keeps five baseball bats in his office, including one

signed by St. Louis Cardinals greats Stan Musial and Albert Pujols.

He likes to swing the bats while he thinks. During earnings calls,

he is known to poke people with a bat if he thinks they aren't

doing a good job of talking to investors.

He has delivered steady gains for investors. Since he took over

in October 2000, Emerson shares have logged a 311% total return,

including dividends, compared with the 275% return from the S&P

500 index, and a 239% return for the S&P Capital Goods Industry

Group Index.

He was just 45 when he was named CEO. Months into the job, he

faced the bursting of the dot-com bubble in 2001 and the Sept. 11

terrorist attacks. The company's 43-year streak of earnings growth

came to an end.

In an era of shrinking CEO tenures, Mr. Farr's has also spanned

the 2008 financial crisis and the 2014 racial unrest in Emerson's

hometown of Ferguson stemming from the fatal police shooting of

Michael Brown, an unarmed Black teenager. Mr. Farr plans to retire

next year, which means the pandemic will likely be his final

challenge.

Though he didn't serve in the military, Mr. Farr approaches

crises as if he was commanding his troops from the front line. "I'm

not going to die, " he said in the first weeks of the pandemic.

"I'm too busy to die."

Downward slide

As February turned to March, the virus ebbed in China but

emerged in a new hot spot: Northern Italy, where Emerson has five

factories and nearly 2,000 workers. The government locked down

areas around Lombardy and Milan, then widened the shutdown to other

regions and eventually the entire country.

"Is it going to grow in just pockets or is it going to grow

across the whole country?" Mr. Farr wondered.

A major Emerson conference for European customers scheduled for

mid-March in Milan was canceled. The company pulled out of an

oil-and-gas conference in Houston. In the relatively untouched

U.S., Emerson started shutting down offices and giving employees

instructions for working from home.

In early March, St. Louis reported its first case of

coronavirus. Shortly after, pharmaceutical giant Bayer temporarily

shut down a major facility just outside of St. Louis when an

employee was suspected to have become infected.

Mr. Farr went forward with a March 10 dinner with Emerson's

latest class of new M.B.A. hires.

The annual dinner and drinks was a tradition. Emerson hosted the

group in a private room at the Saint Louis Club. Mr. Farr loved to

attend and spend time with what could be Emerson's next generation

of leaders. He relished the mentor role and all that came with

it.

"I'm shaking your hand so go wash your hands when I stop," he

told them as he held their grip. The company would end up tracking

the group for 14 days after the dinner to make sure no one got

sick. No one did.

The day after the new-hire dinner, Mr. Farr arrived at J.P.

Morgan's offices in Midtown Manhattan to meet with analyst Steve

Tusa. The bank had changed its investor conference to a virtual

event, but Mr. Farr was intent on participating in person -- he

believed in-person interactions were crucial to running a

business.

It was Wednesday, March 11. Later that day, the National

Basketball Association put its season on hold after a player for

the Utah Jazz tested positive for the coronavirus, the first time

many Americans realized the virus would disrupt their daily

lives.

Seeing Manhattan's vacant streets made Mr. Farr realize the

virus was coming fast and might get bad. He mentioned to Mr. Tusa

how empty New York was.

"We need a different plan," he wrote in an email that weekend to

the other members of the OCE.

Two of the members were already in quarantine for two weeks

because they were just getting back from vacations. Meanwhile, a

worker on the fourth floor of the headquarters building had come

down with symptoms resembling Covid-19 after a ski trip in

Colorado.

Over the next few days, the company decided to shut down most of

the building and have most people work from home. The executives

stayed on the sixth floor. Mr. Farr paced the quiet offices and

looked out with frustration at the empty parking lots.

It took 15 days for the test results of the suspected infection

to come back. It was negative.

"I can't just wait for 15 days to take action," Mr. Farr

said.

South of the border

At a small manufacturing facility about 100 miles from the U.S.

border in the Mexican state of Sonora, an Emerson supplier makes a

tiny component for a communication circuit used in numerous Emerson

products. Officials in Sonora shut down the facility in late

March.

"Every day we fight in Mexico" with its federal government, Mr.

Farr said. "The Mexican president has not been really in tune to

try and keep a coherent strategy."

He turned to Mike Train. The executive was an Emerson lifer who

began his career in Hong Kong, where he was roommates with a young

Mr. Farr, then running the Asia region. Already a close adviser, he

had now emerged as something of a fixer.

When Pennsylvania shut down an Emerson foundry in Erie, dubbing

it a "non-life-sustaining business," Mr. Train navigated federal

and local bureaucracies to get it and other U.S. facilities back

online.

Now his biggest problem was in Mexico, where Emerson has 19

factories with 10,000 employees. "There was never any thought that

[Mexico] was going to be a problem in our supply-chain

architecture," Mr. Train said. "Until it was." The key was getting

certified as "essential."

With a few hundred coronavirus cases emerging in Mexico, the

governors of several Mexican states issued stay-at-home orders and

told nonessential businesses to close.

Mr. Train enlisted the Mexico ambassador in Washington to

coordinate with her counterparts in Mexico City in a push to

reclassify Emerson's plants. It failed.

Mr. Farr reached out to the White House for help, including

talking to President Trump to make his case. "The president said

just move the plants back" to the U.S., Mr. Farr said. "That is a

good idea sure, but not something we can do today."

Mr. Farr was hearing from executives at other companies who were

complaining of restrictions in Mexico.

Emerson teamed up with some, including Honeywell International

Inc. and Trane Technologies PLC, to set up Zoom calls with regional

governors and other Mexican officials to get the designations

needed to keep their operations running.

Within days, more than 300 CEOs had signed a letter calling for

help with supply-chain issues and getting companies the "essential"

label.

Emerson outfitted its Mexican facilities with safety equipment,

made sure distancing requirements were met and installed outdoor

washing stations for workers before they entered the buildings,

among other moves. It couldn't make changes in workers' behavior

outside of work, where the company thought most people were getting

infected.

It wasn't until May that Emerson's Mexico operations were fully

authorized to reopen.

Elder statesman

By mid-March, the OCE was meeting in person every day at 2 p.m.

to review virus statistics, updates about workers and talk about

issues at Emerson facilities around the world. The executives also

discussed their own stress relief efforts, including where to find

deals on the best wines.

Mr. Farr worried about his workers' well being. He prided

himself on knowing employees, walking factory floors and visiting

dozens of facilities a year.

Outside the company, Mr. Farr knew that investors were concerned

about what was happening. There was little information. Companies

such as FedEx Corp. and Ford Motor Co. were declining to give

financial guidance or were withdrawing their previous outlooks

altogether.

Mr. Farr decided Emerson needed to report its second-quarter

results and provide an outlook earlier than usual. He wanted to lay

it all out for investors so they knew where Emerson was going, and

he wanted to do it before other industrial companies. Among the

giants, only GE by early April had issued a warning its latest

quarter would miss its profit goal.

Mr. Farr saw himself as an elder statesman of U.S. manufacturing

-- he is now the longest running leader in the sector. "I've known

four Caterpillar CEOs since I've been CEO," he said. "I felt that a

lot of investors would look to me to get a sense of what is going

on."

He set a board meeting for mid-April to review results. He knew

the board would have questions about Emerson's cash position, its

ability to protect the dividend and its future direction, including

active acquisition talks. He figured the company faced five or six

tough quarters to get through the crisis.

Mr. Farr wanted reports from the business units on their plans,

and he wanted to know what programs needed to be protected so they

didn't slow down. He was watching to see who was stepping up to

keep operations functioning, and who was disappearing. "And I don't

forget," he growled.

On April 21, Emerson reported financial results for the second

quarter, which ended March 31 and included only a few weeks of the

U.S. shutdown. Profits fell 1% and sales dropped 9%. Underlying

orders only fell 3%, but Mr. Farr warned investors that the "real

impact started in the last 2 1/2 weeks in March."

Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., Macy's Inc. and dozens of other

corporate giants had slashed their dividends. Mr. Farr declared

that Emerson's payout was sacred and wouldn't be cut.

"I'm not dead though people have tried to kill me. I'm still

quite strongly in charge. And as long as I'm here, our dividend

will not be cut," he said. Emerson had increased its dividend every

year since 1956, and Mr. Farr was privately planning another

increase in November.

Emerson surprised Wall Street by being one of the few companies

to give a financial outlook for the year, cutting its sales,

earnings and cash-flow projections.

"Thank God we're not in the travel industry," Mr. Farr said on

the earnings call.

Mr. Farr laid out his strategy for returning to work. The

economy couldn't wait for a vaccine. He said widespread testing

with quick results was the key to being able to operate alongside

the virus. Until then, companies and workers needed to do the best

they could to minimize the spread. He revealed that an Emerson

worker in England had died from Covid-19, the company's first death

from the virus.

The detailed disclosures in the two-hour call won praise from

analysts. Mr. Farr said it was necessary during the pandemic but

warned them not to get used to it.

"We'll never give this much information again," he said.

Back to the office

Mr. Farr marked down May 4 -- the first date the governor of

Missouri said businesses could start reopening offices -- as the

day to open up the headquarters building.

People were starting to go outside. The sun was shining in St.

Louis. The weekend before, Mr. Farr and his wife played golf for

the first time since December. They walked 14 holes. He played

horribly. A hairdresser came to the house to give them both

haircuts. On Sunday, Mr. Farr climbed a ladder and cleaned the

kitchen chandelier for the first time in years.

Some executives were leery about reopening quickly, but Mr. Farr

was determined to move faster.

The factories were more or less already humming around the world

because they were deemed essential. Adjustments were made to keep

plant workers safe, including temperature checks, spacing out work

and splitting shifts in some locations.

His strategy for headquarters was to take it step by step,

reversing if any problems arose.

Before the shutdown, the long, low-rise corporate building

typically had about 300 workers. Inside the front door there were

stations for employees to go through: a temperature check, a list

of questions to answer and supplies of masks if people wanted them.

There was a nurse on hand.

One of the biggest debates was about requiring masks. The OCE

executives went through the questions. Were they helpful? When

should they be used? How vigilant should a company be in pushing

for compliance?

Missouri didn't require mask use in public, and messages from

health and political leaders were conflicting. For months, Mr.

Trump refused to wear a mask and declared their use as

voluntary.

Mr. Farr had worn a mask twice since the lockdown began. Once

was during his home haircut and another was on a trip to a

Walgreens pharmacy.

The sixth-floor executives generally weren't wearing masks in

the office. Executives didn't need them, they thought, if they just

stuck to their regular paths. They decided that employees coming

back to work would wear them in open, common areas like the

cafeteria and elevators.

"If you're not feeling well, or if you're running a temperature

or you're coughing, you need to leave the premises," Mr. Farr said.

"We've gone that route, rather than where everyone wears a

mask."

Workers came back in groups through May, with the final batch

after Memorial Day.

But summer was making Mr. Farr uneasy. A CEO could safeguard

offices and factory floors, but that meant nothing if workers

weren't safe while off the clock.

The weather was improving and two holidays loomed as giant traps

for a population eager to break out after a lonely few months.

People were likely going to see family on Mother's Day. Then there

was Memorial Day, when everyone celebrated the unofficial start of

summer with barbecues, drinking and forgetting about the rules.

Mr. Farr saw his neighbors having parties and knew people

weren't behaving themselves. "Those are the things I have to worry

about on a daily basis rather than figuring out what competitor I

want to kill," he said.

He noticed that when employees saw executives weren't wearing

masks, they would remove their own.

Mr. Farr changed his habit, and started donning a mask to walk

down the hall to the restroom. "We got really used to having the

run of the place, " he said. "If there's more of us around, you got

to be doing the right things, you've got to be following your own

rules."

Another challenge

Summer brought more trauma after the killing of George Floyd, a

Black man, in police custody in Minneapolis. It reignited protests

in Ferguson, which was racked with unrest after the 2014 killing of

Mr. Brown.

More than 200 employees joined virtually with Mr. Farr and other

executives to discuss racial issues in the company and society.

Black employees shared their experiences, and Emerson discussed

increasing diversity at all employment levels.

Despite the virus's continued spread and social unrest, Mr. Farr

was feeling more comfortable with Emerson's financial performance

and signs of strengthening orders. "The data's telling me the

bottom's going to start forming," he said.

Mr. Farr had enough experience with crises to know that the

winners were the ones who were ready to supply products to

customers when demand increased. Those pivotal times remade entire

industries.

In his experience, he said, market share rarely shifted in

Emerson's businesses, so customers won't leave "unless you really,

really f -- up."

In the midst of the crisis, Mr. Farr was quietly pursuing an

acquisition to bulk up Emerson's Power & Water business. He had

been negotiating terms with Open Systems International Inc., a

Minneapolis-based developer of software used by utilities to manage

power grids.

Emerson had been watching the privately held company for years

and thought they were ready to sell under the pressure of the

pandemic. Any deal would cost more than $1 billion.

At the same time, Mr. Farr was also exploring a deal for OSIsoft

LLC, a SoftBank-backed maker of software to capture data from power

plants and other industrial facilities. It was a larger business,

and that deal would be much more expensive. Both companies had

multiple bidders circling.

At the June board meeting, an Emerson director asked if Mr. Farr

could guarantee that his decision to quickly increase investment in

businesses with hints of improvement would work.

"No. I can't guarantee s -- ," Mr. Farr replied. "But I'm

telling you right now, based on my experience of being around this

business for 40 years and being CEO of this company for over 20

years, I can tell you my intuition tells me if I see certain

evidence [of improvement], we're going to be pushing it."

'Ask for forgiveness later'

Mr. Farr had just gotten off the phone with KPMG LLC, Emerson's

auditors since 1938, and he was steaming. The problem: It was June

and they were still working from home.

"Look. I make s -- , and you can't tell me how I'm making s --

when you're sitting in your goddamn living room," Mr. Farr recalled

yelling days after the interaction. "Get your a -- out to my

factories, look at my people on the line, and tell me if they're

telling me the truth or lying. That's what you're supposed to do.

That's why I pay you $25 million a year."

Mr. Farr felt remote work was bad in the long-term, so much so

that he had advised his son to get back on the road for his job as

a field marketing manager for Caterpillar Inc. in Atlanta before

the company began bringing people back.

Travel, pay for it yourself, ask for forgiveness later, Mr. Farr

barked at his son.

At the same time, he worried about the safety of his daughter, a

pastry chef in a Manhattan restaurant. She had refused to leave New

York -- an early virus hot spot -- even after Mr. Farr implored her

to come home to the less-crowded Midwest.

Before the pandemic, Mr. Farr usually spent about a third of his

time traveling. As summer started he planned a trip to an Emerson

plant in Pittsburgh in June and a meeting with investors in August.

He also scheduled business trips to Germany and possibly

Romania.

"I have a large organization and operation there, I'd like to

get in there and see what's going on," he said. "And then we'll

most likely go into Tokyo and then Seoul."

On June 16, he flew to Pittsburgh on a corporate jet holding

only half of its usual limit of 10 people. "It was very energizing

to be on the plane," he said.

His mood changed when he saw the airport was empty. He could see

more than two dozen parked commercial airplanes. The state's

policies were "messed up," he said to no one in particular.

A team of executives were there to meet the CEO at the airport.

The group jumped into vans and drove across town. There was no

traffic.

The Power & Water leaders took the CEO to a conference room

to discuss the operations and financial targets. Mr. Farr couldn't

walk the factory floor. The site managers had asked him to stay

away in order to avoid safety risks to workers and the visiting

executives.

That was fine with the CEO. He was just happy to be out working

with his people. He planned to fly to Boulder, Colo., the next week

for another business review.

"It's all going back to trying to make people feel like we're

back in business, it's back to normal, it's safe, I'm here to

talk," he said. "People are getting tired of [video calls] and

stuff like that."

There was a summer surge in Covid-19 cases around the country.

Still, Emerson wasn't changing anything about its overall

operations. It was closely watching the data near its facilities

and "communicating the s -- out of everybody," according to Mr.

Farr. He sent a letter to employees reminding them "have a good 4th

of July, but behave."

Faced with growing infection numbers, Mr. Farr canceled the

Europe and Asia trips.

Even though he had concerns about board members coming in from

states like Texas and Florida, he decided to stick to plans to hold

Emerson's August board meeting in person. Virtual board meetings

weren't good for companies, he thought, and the directors needed to

be together in person to properly oversee a business.

"You got a company going through a crisis and none of the

directors, who represent the shareholders, are here," said Mr.

Farr, who is also Emerson's chairman and a member of the board at

International Business Machines Corp. They can't read body language

or have a free-flowing conversation, he said. "I know boardrooms

think they're doing the same as always, but they're not."

'Not satisfying our customers'

Months into the pandemic, Mr. Farr felt people were learning to

live safely with the virus, and he wanted them back at work.

By July, the sight of empty parking lots was still a trigger --

even at other companies. The lot at the offices of Express Scripts,

a unit of insurer Cigna Corp., set him off. "I can't believe this

thing. It's July 7th," he said.

Mr. Farr was so annoyed he groused that he ought to call Cigna's

CEO and ask if he had closed the Express Scripts headquarters.

Cigna, in response to a query, said it was following guidance

from state and local health officials and was taking a phased

approach to reopening.

Daily new cases were rising, but death rates were far from their

peak in April. He believed the U.S. strategy to flatten the spread

of the virus and not overwhelm medical resources was effective, but

was never intended to eliminate the virus. He was frustrated that a

local virus task force was warning the public about coming dangers,

and blamed the media for alarmist headlines.

He wasn't discounting the crisis, but thought the country was

managing.

The July 4 holiday didn't cause a jump in Covid-19 cases at

Emerson. The daily meetings for executives to discuss the virus had

been reduced to twice a week.

July was also the beginning of Emerson's fiscal fourth quarter,

traditionally its strongest of the year. It hadn't yet reported the

third-quarter results, but Mr. Farr said his estimate of a 15%

sales drop was accurate. He could see the commercial and

residential division, a mix of businesses including tools, heating

and air conditioning, started to improve in late June. He expected

the automation division, which supplies factories, oil producers

and utilities, to lag but follow the same trajectory.

He didn't expect sales growth to return until the second half of

2021, but saw encouraging signs. White-Rodgers, an Emerson unit

that makes thermostats and HVAC controls, was seeing higher demand

from equipment manufacturers.

Still, nagging problems persisted. The Racine, Wis.,

Insinkerator division struggled to keep its production lines

running as cases spread -- just as home renovations turned out to

be a bright spot in the pandemic economy. Mr. Farr offered to send

workers from the St. Louis area to help, but local managers

declined. They asked salaried workers in Wisconsin to pick up

shifts in the factory.

"We're not satisfying our customers, to be frank," said division

president Joe Dillon in July. "We're doing our best on a daily

basis to satisfy as many customers as we can, but it's

challenging."

Mexico had shown signs of improvement, but between 5% and 7% of

Emerson's workers there still weren't showing up for work -- down

from 15% absent earlier in the pandemic.

The Mexican government had encouraged companies to pay workers

100% of their wages even if they were idled. After a few months,

Emerson started cutting back the payments to 75%, then to 50%.

"When we hit that number, it's amazing how many people wanted to

come back to work," Mr. Farr said.

Emerson moved some production of critical parts out of Mexico to

locations with extra capacity in the U.S. and Southeast Asia, but

production still wasn't enough. The headaches spurred a broader

assessment of the company's operations in the country.

"Mexico is the only place I've seen that I have to really assess

my manufacturing facilities," he said.

Ready for the upswing

In the first week of August, Mr. Farr brought Emerson's top 30

executives to headquarters to talk strategy and expectations for

fiscal 2021 and 2022. The discussion centered on how the different

businesses would return to growth and when to commit people and

capital to take advantage of that upswing. There were also dinners

and socializing, the same sort of behavior that he warned against

in missives to workers.

"I got to see some of them for the first time in several months.

It was pretty exciting, and I drank too much," he said. "I mean,

these are things you do all the time and we haven't done it for a

while so it's like, 'OK, we've got to make up for everything we

missed.' "

The dinners were outside with tables of eight set for three or

four people. But mingling was hard to stop. "People were a little

closer than 6 feet," Mr. Farr admitted the next day.

Typically Emerson sees fourth-quarter sales growth of 6%-8% from

the third quarter, but this year he thought it could be double that

rate. As Mr. Farr had stressed in recent months, now was the time

when the plants needed to be running well to meet demand.

The surge was mostly coming from the commercial and residential

division, which benefited from DIY renovations and from hot weather

driving air conditioner demand. Sales in the unit typically drop

5%-10% in the fourth quarter from slowed construction and European

vacations. Now it was expected to swing to positive growth of

5%-10%.

Many of Emerson's customers had run down their inventory and

needed to replenish as business started coming back.

The company reported its third-quarter financial results on Aug.

4. They were largely in line with Mr. Farr's forecast in April,

including a 16% sales drop. Emerson also said its full-year profit

would be better than it thought.

Mr. Farr updated investors on cost-cutting efforts and said

sales in the first three months of 2021 could begin growing.

Keeping factories running safely would be vital, he told

investors.

Reconfiguring factories for worker safety was spurring permanent

changes. Mr. Farr didn't want to build more floor space to solve

the problem. "We're going to have to bring in automation," he said.

"We're going to have to take labor out."

While Mr. Farr's attempt to hold an in-person board meeting

again failed, he continued to pursue a takeover of Open Systems,

the maker of power-grid software, and the much larger potential

acquisition of OSIsoft.

On Aug. 25, OSIsoft was bought by a British industrial software

company Aveva for $5 billion -- Mr. Farr had dropped out of the

bidding when the price went above Emerson's threshold.

Two days later, Emerson announced it was paying $1.6 billion in

cash for Open Systems. The deal expanded Emerson's power-station

management software into renewable power sources, an increasingly

important part of the industry.

Moving forward

Over the summer, Mr. Farr had resumed site reviews around the

country, making quick day trips on the company jets to Texas,

Wisconsin and New Jersey. He expected planning sessions with

business leaders to begin in December or January. Instead of unit

leaders having to come to headquarters and present their plans, he

would visit them. Trips to visit companies in Europe or Asia would

have to wait.

The pandemic didn't slow Mr. Farr's retirement plans. He

expected the company to stabilize by the time he planned to step

down at the end of 2021. In August, he told Bob Sharp, the head of

the commercial and residential business, that he wouldn't be chosen

to succeed him, prompting Mr. Sharp to leave Emerson.

Emerson's annual October strategic meeting was held at

headquarters. About 110 people traveled to the meeting for two days

with 600 others attending over video. The executives spread out in

an auditorium for two three-hour sessions.

He was also pushing to get leadership development training back

on the schedule. He figured the pandemic cost Emerson a year's

worth of time in developing future leaders, something he considered

crucial. He didn't want to fall further behind.

And as he had pledged back in the spring, Emerson increased its

quarterly dividend in early November by half a penny to 50.5 cents

a share, marking 64 years of regular increases.

More than 10 months into the pandemic, Mr. Farr was still as

confident in November as he was at the outset that the deadly virus

wouldn't permanently change how people live. He saw the crisis as a

vindication of his instincts and management methods.

"As soon as you hear someone say 'the new normal,' plug your

ears, and say, 'bulls -- ,' " Mr. Farr said. "Since I've been CEO

I've seen a lot of new normals."

He described his effort to attack the crisis with a combination

of analysis and gusto. "Once we saw that it was going to really

impact our business or the communities or the world that we're

operating in, [the strategy was] basically to break it down just

like any planning process, " he said in November. "If you ran into

a wall, like the states trying to shut us down, you ran at the wall

and you tried to figure out how you climb that wall."

As of Nov. 30, nearly 2,500 workers at Emerson had fallen ill,

and seven had died.

Mr. Farr was adamant that he would get a vaccine once it was

available -- and wanted his workers to do so, too. "I just think

that the amount of pain we've gone through as a nation and as a

world and business world, if you don't get a vaccine, you're a

hypocrite," he said. "If you don't worry about this thing,

something's wrong with you."

Emerson plans to reconfigure its more than 200 manufacturing

facilities around the world over the next year using automation so

it can space out workers but maintain production at pre-pandemic

levels.

In Mexico, the review led Mr. Farr to determine certain areas

weren't suitable for future expansion. Another review produced

plans to build more backup systems into its global supply

chain.

Mr. Farr's efforts to get the Emerson board to meet in person

still haven't succeeded -- the October board meeting was also

virtual. But the CEO has been able to travel. In November, he went

to the Masters Tournament with his wife at Augusta National Golf

Course, where he is a member. And he slipped into Manhattan to meet

investors for a face-to-face dinner in a private room. He planned

at least one more similar meeting this year.

Demand is rising among Emerson's customers, so it is hiring more

staff than usual -- even though it cuts into profits -- to make

sure production isn't slowed if workers become sick.

Mr. Farr hasn't stopped coming to the office. There is more

traffic on the roads in St. Louis, but the parking lots around town

are still mostly empty.

He suspects his industrial rivals aren't back in their offices

yet either. "I like competitors that are still sitting at home," he

said. "They'll miss the trains when they go by."

Write to Thomas Gryta at thomas.gryta@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

December 04, 2020 10:31 ET (15:31 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

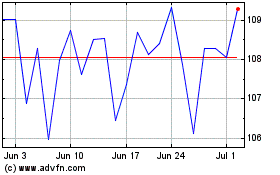

Emerson Electric (NYSE:EMR)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

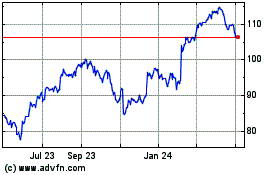

Emerson Electric (NYSE:EMR)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024