By Drew Hinshaw and Gabriele Steinhauser

Rich countries have preordered more than three billion doses of

Covid-19 vaccines, threatening to leave poor nations struggling to

inoculate more than a fraction of their billions of people and

raising the prospect that the disease could spread for years to

come.

Now, with three Western vaccines showing promising effectiveness

and a coalition of international health agencies gaining traction,

there is cautious optimism in the world's poorest countries as they

scramble to secure some doses.

Europe and America have reserved enough Covid-19 vaccine doses

to inoculate their entire populations, claiming the shots before

they are even manufactured and squeezing supply for other

countries. Meanwhile, China has mainly allocated its vaccines for

its own 1.4 billion citizens, outside of a few thousand people in

the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain.

That has left many governments in Africa, Latin America and

South Asia dependent on a small cluster of international and

nongovernmental health agencies based in Switzerland, particularly

the World Health Organization, and GAVI, a Geneva-based

organization that stockpiles vaccines. Collectively, those agencies

hope to vaccinate at best 20% of the population of the world's 92

poorest countries by the end of next year, primarily health-care

workers, the elderly and those with other diseases that make

Covid-19 more deadly.

That effort has been picking up steam in recent days.

On Monday, AstraZeneca PLC and the University of Oxford

announced their vaccine appears to be up to 90% effective. The

developing world has laid its hopes on that vaccine, since it is

priced at just a few dollars a dose and can be transported and

stored for six months in ordinary refrigerators, making it best

suited for countries that lack a sophisticated network of ultracold

freezers. GAVI has purchased some 300 million doses of the vaccine,

enough to inoculate around 100 million people, assuming that some

doses will go to waste because of refrigeration problems or other

issues.

But other vaccines are gaining some traction in the global South

as well. GAVI says it is in talks over whether to buy doses from

Pfizer Inc., which now says its vaccine, produced at ultralow

temperatures, can be stored in ordinary refrigerators for up to

five days. It is also in discussions with Moderna Inc., which says

its vaccine can last for a month in a fridge.

GAVI has raised the $2 billion it needed this year to fund

vaccine purchases, though officials there said they would need to

find another $5 billion next year. The institution expects to hold

talks soon with President-elect Joe Biden's team on increasing U.S.

support for the global vaccination drive.

It is still an uphill battle. "What we need to recognize is that

first and foremost we are going to be in a situation of short

supply of vaccines for the year ahead of us," said Managing

Director Aurélia Nguyen of GAVI's vaccination effort. "Something

like this has never been attempted before."

At stake is whether the developing world becomes a reservoir for

an airborne disease that could continue to circulate and claim

lives on the back of global trade and travel. In many low-income

countries, lockdowns and other restrictions on social and economic

activity have already rolled back decades of progress in health

care, schooling and poverty reduction. Delays in getting a vaccine

would push them still further behind.

As vaccines emerge, global public-health specialists worry about

a future in which the burden of Covid-19 shifts onto much poorer

countries, where the virus may linger, perhaps for years.

WHO officials have raised the possibility that, given the

challenges of vaccinating the entire global population, the new

coronavirus might never go away, and will instead become endemic to

the human population, like other vaccinable diseases such as

measles.

Only two diseases have ever been eradicated using a vaccine:

smallpox, and the cattle-spread viral infection rinderpest. Others

have proven stubbornly resistant, like polio, which was only fully

eradicated from Europe in 2002, half a century after a vaccine

emerged, and which remains present in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

For Covid-19, the potential cost in lives is considerable: If

the world's 50 richest countries secure the first two billion doses

of vaccines, the pandemic's ultimate death toll will be twice as

large as it would be if supply was shared more evenly, a study

funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and conducted at

Northeastern University found in September.

And there are other risks: Some virologists worry that the virus

could mutate in ways that render current vaccines ineffective.

"It is absolutely in the U.S. interest to make sure the world

gets vaccinated as well," said former U.S. Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention Director Tom Frieden. "This isn't just an

ethical position, though it is of course ethically correct. It's a

practical issue."

So far, it isn't clear whether the current vaccines, which have

proven to work well in more-developed countries, will be as

effective in poorer parts of the world. Differences in nutrition

and the prevalence of other health conditions, such as HIV, could

make vaccines less effective in poorer countries, vaccine experts

warn.

That has been the case with other vaccines, such as the one

against rotavirus, which can cause severe diarrhea in children. The

data supporting the announcements from Pfizer, Moderna and

AstraZeneca stems from trials in rich countries like the U.S. and

the U.K. and middle-income countries such as Brazil.

Even if developing countries can secure enough doses, huge

logistical challenges remain to get them to the people who need

them. Just 10% of health centers in developing countries have

reliable electricity supply, while about half have no electricity

at all, according to GAVI.

That means even keeping doses refrigerated between 2 and 8

degrees Celsius can be difficult, said Marco Gaudesi, a pharmacist

who manages temperature-controlled supply chains and other

logistics for Doctors Without Borders.

Health-care workers in poor countries also usually have

less-specialized training, so may struggle with vaccines that

require mixing different vials before being administered or have to

be thawed from subzero temperatures. "There are so many smaller

differences that might not have an impact in developed countries

that may have an impact in a different context," said Mr.

Gaudesi.

Still, WHO officials are less concerned about so-called cold

chain issues than they once were. After detailed discussions with

drugmakers over transportation requirements and packaging, GAVI and

the WHO have decided they don't need to massively invest in the

kind of extensive array of ultracold freezers they used to

distribute an Ebola vaccine in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

AstraZeneca's vaccine doesn't require that kind of storage, and

Moderna's candidates can be dispatched in refrigerated

vehicles.

"Based on the analytics that we have, it's not that we have to

expand the cold chain to some extraordinary degree we've never seen

before," said a senior WHO official. "It's not the major

issue...it's something you can plan for."

Write to Drew Hinshaw at drew.hinshaw@wsj.com and Gabriele

Steinhauser at gabriele.steinhauser@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

November 25, 2020 08:14 ET (13:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

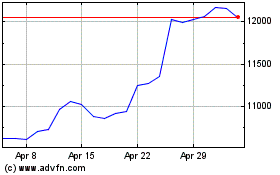

Astrazeneca (LSE:AZN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Astrazeneca (LSE:AZN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024