By Aaron Tilley

The Trump administration's campaign to make Chinese-owned

video-sharing app TikTok relocate to the U.S. is the latest example

of the global fracturing of the internet.

President Trump over the weekend approved in principle a deal

that would shift TikTok's headquarters and data to the U.S. Chinese

owner ByteDance Ltd. and its investors, for now, remain the

majority shareholder, with Oracle Corp. taking a 12.5% stake in the

new company, called TikTok Global, and Walmart Inc. owning 7.5%.

Oracle will serve as a technology partner to assure the U.S.

government that user data is safe, the companies have said.

With the move against TikTok, the U.S., in effect, is following

steps a number of other governments have taken to treat their

citizens' data as a national-security issue and impose restrictions

on how data is stored and shared. Mr. Trump raised concerns that

China's government could tap TikTok's data on American users

because the app is Chinese-owned. TikTok has said it wouldn't share

the information.

Treating user data as a matter of national security is a notion

that has dictated many of the policies Beijing has put in place to

control the internet in its country for the past decade. China

operates what is called the "Great Firewall," limiting the services

people in the country can use and the information they receive.

Beijing stops people from accessing services run by FacebookInc.

and Alphabet Inc.'s Google, instead steering them toward

Chinese-owned alternatives such as WeChat and Baidu Inc. that it

controls increasingly tightly.

The idea that those data flows need tighter control has spread

in recent years, resulting in a number of instances when

governments temporarily shut down the internet. Governments have a

range of motivations, from squelching internal dissent to

protecting their citizens' privacy.

The European Union, which put in place strict conditions on

overseas data transfers two decades ago, has broadly tightened its

safeguards for its residents' information with its General Data

Protection Regulation. India has followed, erecting roadblocks

through special requirements for how U.S. tech companies structure

their operations and handle data collected from Indian customers.

India this summer also banned dozens of Chinese apps, citing

national-security concerns, amid a lethal border skirmish with

China.

Those measures can come with high costs for tech companies, many

based in the U.S. and China, that are built on an internet with few

borders. Google pulled out of China a decade ago, losing access to

the vast market. Facebook, blocked in China, could face a potential

multibillion-dollar fine in Europe over its data practices.

Microsoft Corp., which also vied for TikTok, in China limits

content on its Bing search engine and LinkedIn business-focus

social-networking site.

"U.S. tech companies have far more to lose if this becomes a

precedent," said Aaron Levie, chief executive of Redwood City,

Calif.-based Box Inc., a fast-growing cloud-computing company.

"This creates a Balkanization of the internet and the risk of

breaking the power of the internet as one platform."

Some U.S. lawmakers, for some time, have urged the government to

retaliate for China's efforts to exert control over the internet.

Even before the U.S. took steps to force changes around TikTok's

data, U.S. national-security officials ordered another Chinese

company to sell gay-dating app Grindr, citing the risk that the

personal data it collects could be exploited by Beijing to

blackmail individuals with security clearances, according to people

familiar with the situation.

The drama around TikTok and its 100 million American users was

far higher, though, with President Trump threatening to shut down

the app absent a sale. By targeting TikTok as well as WeChat, the

ubiquitous-in-China messaging and payments app owned by Tencent

Holdings Ltd., Washington has effectively enacted measures to

create data-privacy rules, but in a way that can be difficult for

companies to handle, said Paul Triolo, head of the global

technology policy practice at Eurasia Group, a political-risk

consulting firm.

"With these actions, the U.S. is basically making up a rule that

no Chinese person or government can have access to the data of a

U.S. citizen," Mr. Triolo said. But, he said, "trying to set up a

data-protection regime using executive orders is really messy, as

this whole thing is turning out to be."

Adam Mosseri, chief executive of Facebook's Instagram, tweeted

on Friday that a U.S. ban on TikTok "would be quite bad for

Instagram, Facebook, and the internet more broadly."

It isn't just the U.S. and China that eye each other with

distrust. The European Union's top court in July struck down one of

the main legal mechanisms companies use to store information about

EU residents on U.S. servers, arguing that such transfers exposed

Europeans to American government surveillance without "actionable

rights" to challenge it. The ruling also restricted another legal

mechanism companies had used as a backup, leading an EU privacy

regulator to start the process of ordering Facebook to cut off

EU-U.S. personal-data flows, which the company is appealing. The

legal challenge that spurred the July ruling dates to the 2013

leaks of alleged U.S. surveillance practices revealed by former

National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden that showed some

U.S. companies were sharing user information with the

government.

U.S. concerns about China have increased in recent years, in

part driven by the massive hack of records held by the Office of

Personnel Management in 2015 that exposed sensitive data on

millions of Americans. The U.S. suspected China was behind the

attack, which Beijing denied.

The U.S. action on TikTok has enraged the Chinese government.

"Without any evidence, they have been abusing national power under

the pretext of national security to suppress and coerce

non-American companies that have a cutting edge of a particular

field," said Wang Wenbin, a spokesman for the Chinese Foreign

Ministry, last week.

The Trump administration also said it was moving against TikTok

to keep Americans safe from online misinformation, an argument

defenders of China's heavy-handed approach to controlling access to

online content in defense of the country's policies also put

forward.

To help address those concerns, TikTok Global won't just have

U.S. investors, but four of its five board members will be

American.

That construct could be a useful precedent for other companies

as they try to determine what arrangements may be acceptable to

Washington, said Winston Wenyan Ma, formerly a managing director at

China Investment Corp., the country's sovereign-wealth fund, and

now an adjunct professor at New York University's School of

Law.

But the TikTok situation that still has many unanswered

questions isn't likely to resolve all uncertainties, he said. "In

this new world, one case can't solve everything."

--For more WSJ Technology analysis, reviews, advice and

headlines, sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Stu Woo contributed to this article.

Write to Aaron Tilley at aaron.tilley@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 21, 2020 08:14 ET (12:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

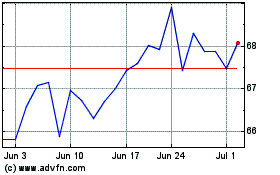

Walmart (NYSE:WMT)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

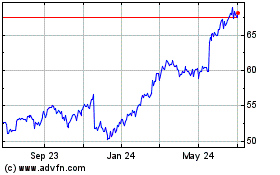

Walmart (NYSE:WMT)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024