Goldman's Traders, Bankers Keep Profit Steady While Rivals Falter -- 2nd Update

July 15 2020 - 12:46PM

Dow Jones News

By Liz Hoffman

Nobody is better at capitalizing on chaos than Goldman Sachs

Group Inc.

Its traders and investment bankers posted near-record revenue to

keep firmwide profits steady, throwing an elbow to larger

commercial-bank rivals that blamed the coronavirus pandemic for

lower quarterly results.

Goldman was buoyed by its Wall Street roots, seizing on a flood

of corporate fundraising deals and torrid trading markets to post

its second-highest quarterly revenue ever, at $13.3 billion. Those

fees were slightly offset by higher reserves for future loan

defaults in what is expected to be a sustained and deep

recession.

The challenge now for Chief Executive David Solomon: not to

learn the wrong lesson. Goldman hasn't seen this kind of activity

since 2010. Its ability then to wring profits from economic turmoil

bolstered its mythical status as a Wall Street heavyweight and

delayed its push into steadier businesses such as consumer banking

and asset management that could help balance the firm when this

crisis passes.

"We became super busy because our clients were super busy," Mr.

Solomon said on a conference call. "I don't necessarily view that

as permanent." He added that market activity has slowed in the past

few weeks from the spring pace.

Quarterly earnings were roughly flat from a year ago at $2.4

billion. Per share, that amounted to $6.26. That far outpaced

expectations of Wall Street analysts, who had expected Goldman to

earn $1.12 billion, or $3.90 a share. Shares rose 1.5% in morning

trading and briefly touched a five-month high.

The second quarter was banks' biggest test in more than a

decade. Unemployment soared, companies lined up for cash and

executives spun up models to see how their businesses would fare in

what is likely to be a deep, and possibly sustained, downturn.

Goldman's good fortune underscores a broader divide that people

have struggled to reconcile in recent months, between a stumbling

economy and a rallying stock market.

Quarterly profits fell 51% at JPMorgan Chase & Co. and 73%

at Citigroup Inc. Wells Fargo & Co. posted its first quarterly

loss in 12 years. The three banks set aside a combined $28 billion

in the quarter to cover expected losses on loans to newly

unemployed consumers and corporate borrowers whose businesses have

evaporated. Goldman, a smaller lender, set aside $1.6 billion.

The current economic crisis isn't a 2008-style banking-system

meltdown, and today's banks hold more blow-cushioning capital than

they did then. But that capital isn't bottomless, and a sustained

recession would eat into it as loans go bad. Last month, the

Federal Reserve ordered banks to continue a hiatus on share

buybacks and capped their shareholder dividends to preserve

cash.

Goldman is considered to be in a better position than larger

commercial banks to weather at least this leg of the crisis.

Without a big mortgage or credit-card business, it is less exposed

to a spike in unemployment or ultralow interest rates.

Net interest from loans contributed just 12% of Goldman's

revenue last year, versus half or more at JPMorgan and Bank of

America Corp. Nearly two-thirds of its revenue comes from

securities trading and investment banking.

Trading revenue nearly doubled from a year ago. Volatile markets

are Goldman's specialty, and a playground the firm hasn't seen in

nearly a decade. Revenue was 149% higher than the same period last

year in fixed-income trading, a more opaque business where better

risk models and sharper noses make a difference during a chaotic

market.

Goldman's investment bankers had one of their best quarters ever

as companies rushed to sell stock and debt to the public to shore

up their finances. Goldman helped raise cash for Ford Motor Co.,

cruise line Carnival Corp. and United Airlines Holdings Inc., each

racing to survive the shutdown. Investment-banking revenue of $2.66

billion was 36% higher than the same period last year, as

underwriting revenues from those deals and others offset a drop in

merger fees.

While the chaos of the quarter helped Goldman's core Wall Street

businesses, it now threatens the firm's new consumer-lending arm,

Marcus, which launched about three years ago and had $23 billion of

outstanding or available loans as of March 31.

All are unsecured loans, which are often the first bills to go

unpaid as struggling borrowers prioritize their home, car and other

collateral from repossession.

Goldman says Marcus is built for the long haul. But its belated

push onto Main Street means it missed the consumer-banking boom

that its rivals enjoyed over the past decade and now faces only the

potential bust.

About one-quarter of the $4.4 billion Goldman has set aside to

cover expected loan losses are for consumer loans, which represent

less than 10% of its total loans, suggesting it expects those to

default at a higher rate than corporate or real-estate loans.

Goldman's balance sheet grew to a postcrisis high of $1.1

trillion as of June 30, with an influx of cash and higher trading

inventory offsetting a decline in loans. Corporate clients borrowed

heavily early in the quarter, but replaced that bank debt with

longer-term bonds after the Fed intervened and markets relaxed.

It plowed excess cash into safe harbors such as Treasury bonds

that offer paltry returns but boost financial resilience. One

measure that tracks assets the bank could easily sell in a pinch

has risen 22% over the past two quarters, a faster pace than

overall assets. "The organization sleeps better at night knowing we

have it," Chief Financial Officer Stephen Scherr said in an

interview.

Write to Liz Hoffman at liz.hoffman@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

July 15, 2020 12:31 ET (16:31 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

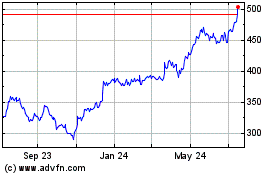

Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

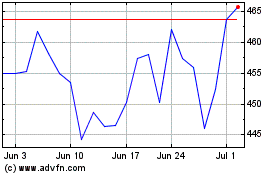

Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024