By Joseph Walker, Peter Loftus and Jared S. Hopkins

For drug companies, there is suddenly only one priority: the

coronavirus.

More than 140 experimental drug treatment and vaccines for the

coronavirus are in development world-wide, most in early stages but

including 11 already in clinical trials, according to Informa

Pharma Intelligence.

Counting drugs approved for other diseases, there are 254

clinical trials testing treatments or vaccines for the virus, many

spearheaded by universities and government research agencies, with

hundreds more trials planned. Researchers have squeezed timelines

that usually total months into weeks or even days.

"We have never gone so fast with so many resources in such a

short time frame," said Paul Stoffels, chief scientific officer of

Johnson & Johnson.

Even so, for most treatments and vaccines it will be midsummer

before human testing reveals whether they are safe to take, not to

mention if they work. J&J is excited about a vaccine prospect

but won't be able to start testing it in humans until September.

Research progress that is remarkable by usual standards remains far

behind the racing virus.

Health officials are warning Americans to brace for the most

difficult days this week, with the number of infections in the

nation's hardest hit cities expected to peak. More than 1.2 million

people have been infected around the globe as of Sunday, according

to data compiled by Johns Hopkins University. In the U.S., more

than 9,400 people have died from Covid-19, the respiratory disease

caused by the coronavirus. The White House projects the U.S. could

see 100,000 to 240,000 deaths from Covid-19.

Vaccines to prevent infections and drugs to treat them can't

come soon enough. Without them, health authorities have had to rely

on containment measures such as travel bans and social distancing,

while doctors sometimes give patients unproven agents with the hope

they will work.

It usually takes years to develop a new drug treatment or

vaccine. After finding prospects, researchers must tweak them to

maximize their disease-fighting potency and minimize the risk of

unwanted side effects. The compounds must be tested in the lab, in

animals and extensively in humans. If they succeed, more time is

needed to manufacture large numbers of doses.

The urgent, high-speed search is moving on three fronts. One is

to get a vaccine that could provide immunity, allowing a return to

normalcy.

Among the farthest along is a vaccine hatched by government

researchers and Moderna Inc., a biotechnology company in Cambridge,

Mass., for which safety testing in humans has begun. If this and

all later clinical studies succeed, it could be ready for use as

soon as early next year, researchers say.

In addition, Inovio Pharmaceuticals Inc. of Plymouth Meeting,

Pa., said human trials are starting today for an experimental

vaccine it is developing. Chinese company CanSino Biologics Inc.

and a research arm of the Chinese military have started human

testing of a potential vaccine, according to the World Health

Organization. In Europe, German company CureVac AG and the

University of Oxford are developing vaccines.

Scientists also are exploring whether existing drugs such as

hydroxychloroquine for malaria or HIV treatments might work against

the coronavirus, and some doctors are already treating patients

with hydroxychloroquine. Results from two Chinese studies of Gilead

Sciences Inc.'s antiviral remdesivir, previously tested in Ebola,

are expected this month. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc, and partner

Sanofi SA are testing a rheumatoid arthritis drug against the

coronavirus.

On the third front, researchers are hunting for entirely new

drugs. Among these efforts, which take longer, are programs to mine

the blood of recovered patients for infection-fighting soldiers

known as antibodies that can be converted into drugs.

All drug and vaccine research is difficult, but tackling a virus

can be especially tricky. Tweaking the immune system, as some drugs

and vaccines targeting infectious diseases aim to do, risks sending

the immune response into overdrive and making things even worse. It

can take researchers several tries to find more powerful

agents.

"I think we can find something that, at least, helps people

out," said Derek Lowe, a veteran drug researcher. "Whether any of

these things work well enough to get people out of their houses,

that's another question. Maybe it works well enough to reduce the

number of people who go on ventilators."

Johnson & Johnson said it and a division of the Department

of Health and Human Services together have committed more than $1

billion of investment to co-fund vaccine research, development, and

clinical testing. Other government agencies and universities are

also spending on research.

Unlike the race to find cures for cancer or other diseases,

there's not necessarily a big payoff at the finish. Companies

haven't indicated what they might charge for medicines if they

work; some have said they'll provide drugs free or at low cost.

Gilead said Saturday it won't charge for 1.5 million doses it has

manufactured for clinical trials and emergency uses, or any

remainder if the drug is approved.

Scenes from several laboratories show the quest from the

inside.

One weekend in January, Kizzmekia Corbett rushed to Building 40

on the National Institutes of Health campus in Bethesda, Md.

Dr. Corbett is a researcher at the National Institute of Allergy

and Infectious Diseases, or NIAID. For years, she and colleagues

have braced for a pandemic, studying bacteria and viruses that

popped up around the world to gain a better understanding when a

bad one finally came.

Around Jan. 10, she got a cellphone alert with a vital piece of

information about a mysterious virus emerging in China. A

consortium of researchers including Chinese scientists had

published online the virus's genetic sequence.

That provided its molecular makeup, crucial information needed

to craft a vaccine for it. The research also indicated the new

virus belonged to a well-known family, the coronaviruses.

Named for the crown-like spikes protruding from their surface,

coronaviruses had caused two deadly outbreaks since 2002: severe

acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, and Middle East Respiratory

Syndrome, MERS.

Dr. Corbett and a colleague studied the genetic code --

seemingly endless combinations of the letters A, G, C and T, each

standing for the chemicals comprising DNA. The sequence looked

similar to that of the SARS virus. This meant researchers who had

investigated a SARS vaccine, which didn't advance after the

epidemic waned, could pursue a similar tack against the new

coronavirus.

A vaccine would deliver a disabled spike protein, or the genetic

instructions to make a close copy, into the human body. The payload

wouldn't infect a person but would train the immune system to

recognize and attack the virus. If a vaccinated person encountered

the virus, antibodies would spring into action and neutralize

it.

"We're lucky that this is a coronavirus because we know what to

do. It would be a much worse situation" if the virus belonged to a

less-studied family, said Barney Graham, deputy director of the

Vaccine Research Center at NIAID.

As the virus spread in Wuhan, China, and then in other

countries, U.S. government researchers searched for a partner to

help design and make a vaccine. Dr. Graham reached out to one his

team previously worked with, at Moderna, which is pioneering a new

technology for making vaccines. It uses "messenger" RNA, genetic

material that can instruct cells to make proteins able to trigger

immune responses.

Like the NIH, Moderna researchers studied the new virus's

genetic sequence when it was published. They, too, concluded the

spike protein would be the best part to target. So did vaccine

hunters at J&J, Sanofi and other companies.

By Monday, Jan. 13, the NIAID and Moderna agreed on a vaccine

design. Moderna quickly made a small batch for testing. Dr. Corbett

and colleagues started testing it in mice on Feb. 4. Two weeks

later, initial results showed it elicited antibodies to coronavirus

in the blood.

Success in mice often doesn't mean a similar result in people.

Months of testing in humans would be necessary. Moderna retrofitted

equipment at its manufacturing plant outside Boston, and by Feb. 25

the NIAID was ready to recruit healthy volunteers. In the past, it

has usually taken many months for an experimental vaccine to start

human testing after selection of a target.

One morning the following month, George Yancopoulos, chief

scientific officer at Regeneron in Tarrytown, N.Y., texted his head

of infectious disease research. "Good luck today," he wrote. "The

world is sort of maybe depending on you ;)."

It was 8:41 a.m. on Saturday, March 14, the latest in a string

of weekends consumed by the company's hunt for a medicine that

could knock out the virus in someone it had infected.

Spearheading the efforts was Christos Kyratsous, drug-discovery

chief for infectious diseases, who used a rapid-response platform

the company had formed after the 2014 Ebola epidemic in West

Africa.

His team collaborated with colleagues who tended some special

mice with immune systems genetically engineered to have a

human-like response to viruses. Because the mice make antibodies

indistinguishable from people's, researchers working with the mice

can have a compound ready to test in people in months rather than

the years it takes to birth a traditional drug from scratch.

The teams had spent weeks collecting antibodies from mice

exposed to the coronavirus's spike protein, in hopes that two of

the antibody molecules could be combined into a drug able to stop

an infection. They also gathered antibodies from the blood of

recovered coronavirus patients.

Experiments to see whether these killed the virus in test tubes

were being finished up that March Saturday.

"You can come now," Dr. Kyratsous texted Dr. Yancopoulos at 2:45

p.m. Dr. Yancopoulos got off a conference call and walked to the

lab. As he entered the lab and saw Dr. Kyratsous smiling, he texted

a colleague to bring a bottle of champagne.

Data showed they had found hundreds of antibodies that blocked

the virus from entering cells. If it couldn't enter cells, it

couldn't replicate. A treatment was still far away -- but now was

in sight. The champagne popped open.

"My head was in a rush: 'We've got it,' " Regeneron Chief

Executive Leonard Schleifer recalls thinking after his chief

scientific officer gave him the details. "The world is starting to

fall apart, and if we can just hold on, in that lab, in those

tubes, is a cure."

Within days, Regeneron announced it would choose the best two

antibodies for a drug in April and would start clinical trials by

early summer. It is preparing to manufacture hundreds of thousands

of doses a month by the end of the summer.

Getting the drug on the market isn't assured. Clinical trials

showing the treatment is both effective and safe could take months.

These are the stages where so many medicines fail even after they

show promising test-tube and animal results.

Neal Browning was scrolling through his Facebook feed in early

March when a friend's post caught his eye.

Mr. Browning is a network engineer at Microsoft Corp. living in

the Seattle suburb of Bothell, Wash., not far from one of the

country's earliest and worst coronavirus outbreaks. He also lives

close to the research center doing a human study of the vaccine

that Moderna and the NIAID are developing.

The research center, Kaiser Permanente Washington Health

Research Institute, was urgently seeking healthy volunteers to test

the experimental vaccine's safety. Mr. Browning's Facebook friend

knew of the recruitment effort. After Mr. Browning expressed

concern about the virus, the friend texted him details of the

trial.

Many medical facilities across the U.S. are seeking people to

test the safety of potential coronavirus drugs or vaccines. To make

way, they are suspending trials of other medicines, clearing space

for coronavirus study subjects and assigning data-entry workers,

pharmacists and other staff to deal with the paperwork.

Massachusetts General Hospital, one day after agreeing to test

Gilead's remdesivir, walked federal health officials through how it

planned to conduct the trial. It did so by phone for safety reasons

and because time was short, said Libby Hohmann, who oversees the

hospital's clinical-trial effort.

That evening, Dr. Hohmann assembled about a dozen pharmacists,

researchers and physicians in a conference room to parcel out

trial's tasks, such as collecting blood samples and tracking

patients once discharged.

To save time, they skipped typical pretrial exercises such as

training the staff in showing hospital doctors and nurses the way

to administer the drug. "We're sort of doing those on the fly," Dr.

Hohmann said.

Since the trial began March 15, Mass General has enrolled 35

subjects. Among them is a man in his 40s who agreed to be in the

study just before nurses inserted a breathing tube down his throat

because of respiratory problems from the virus, Dr. Hohmann said.

He is now stable, she said.

For the test of Moderna's vaccine, Mr. Browning, the Microsoft

engineer, showed up at the Kaiser research institute in downtown

Seattle on March 16, becoming only the second volunteer.

It had been just nine weeks since researchers selected a section

of the virus's genetic sequence to target, which researchers called

the shortest time by at least a month to get a vaccine into the

first stage of human testing. Even so, the trial is unlikely to

have preliminary results until summer, followed by more testing

required that would push the vaccine's availability out about 12 to

18 months, according to the NIAID.

After his shot, Mr. Browning stayed for about an hour so the

staff could make sure he didn't have any side effects. He drove

home and worked that afternoon helping Microsoft configure network

firewalls to accommodate a surge in employees working remotely,

until the threat posed by the virus can be quashed.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 06, 2020 12:26 ET (16:26 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

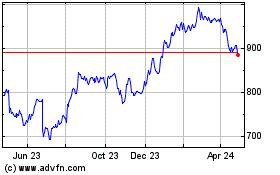

Regeneron Pharmaceuticals (NASDAQ:REGN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

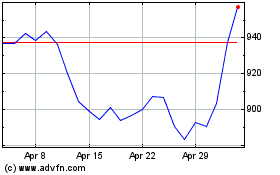

Regeneron Pharmaceuticals (NASDAQ:REGN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024