By Jeff Horwitz

There is no coronavirus vaccine available for dogs being

withheld from humans.

It isn't necessary to close your windows because military

helicopters will start spraying disinfectant.

And baby-formula manufacturers aren't sending freebies to people

who call their customer hotlines.

These are among the viral social-media memes debunked by Lead

Stories, a fact-checking site co-founded by Los Angeles

entrepreneur Alan Duke.

At a moment when there are global scarcities for items as

diverse as toilet paper and ventilators, Mr. Duke offers something

else in short supply: fact checking.

The former CNN producer's company, Lead Stories, helps Facebook

Inc. and other social-media platforms limit the spread of

virus-related misinformation by flagging it as false. Business is

booming, thanks to a surge of posts that are both dangerous and

harder to track than many other forms of what is known as fake

news.

The claims that Lead Stories debunks are then labeled as false

on Facebook, which limits their spread and links to Lead Stories'

reviews. A staffer combs the platform looking to identify and label

duplicates that spring up.

Already ramping up with funding from Facebook to combat

misinformation in the 2020 U.S. presidential election, Mr. Duke and

others in the industry have pivoted to coronavirus almost

full-time.

"We've maxxed out all our goals for the month," he said halfway

through March, referring to the company's contractual targets for

Facebook fact-check volumes. Lead Stories continues to review

Facebook and Instagram content, and review material from Twitter,

YouTube and other platforms that don't pay it, posting fact checks

to its own site. Since its first coronavirus fact check in

mid-January, Lead Stories has fact checked more than 200 viral

coronavirus claims.

Other fact checkers have become similarly focused, organizing an

ad-hoc international task force to identify misinformation that has

hopped national borders and languages as quickly as the virus

itself.

Lead Stories has traditionally battled political publishers and

for-profit hoaxers in places ranging from the U.S. to Macedonia and

Pakistan. While many coronavirus posts carry international content

-- the meme warning of military disinfectant drops appeared in

Europe and elsewhere -- they generally appear to be noncommercial,

produced by pranksters or people promoting misguided home remedies,

Mr. Duke said.

Such apparently organic content also coexists with ideologically

driven falsehoods, such as the claim that "60 Democrats" in the

U.S. Senate blocked coronavirus relief payments to Americans.

The content is often memes and images rather than purported news

stories. And where Lead Stories has become used to complaints from

the publishers of stories it rated as false, it now hears from

regular users upset that it has debunked a meme they shared.

"Sharing this stuff is how people connect to their friends and

co-workers," Mr. Duke said. "It's embarrassing when it shows up in

their timeline that they shared something that's wrong. That's not

something we've been through before with fact checking -- this is

much more personal."

As is common with Facebook's 56 global fact-checking partners,

Lead Stories was launched with independent funding but has

sustained itself in part with Facebook money. The tech giant

started the fact-checking program in late 2016 after criticism of

how it handled misinformation during the 2016 presidential race.

But human fact checkers remain central to Facebook's defenses, and

even before the coronavirus pandemic the company was ramping up its

investments.

Mr. Duke declined to say by how much money Facebook is paying

Lead Stories, but said it was a multiple of the $359,000 it earned

under its 2019 contract.

Mr. Duke and his co-founder Maarten Schenk, who works from his

home in Belgium, were the company's sole full-time employees until

last November, when Facebook told U.S.-based fact-checking partners

that it would bankroll a sharp expansion of their work ahead of the

2020 presidential election.

"Fighting misinformation isn't something one company can do

alone," said Campbell Brown, head of news partnerships at Facebook.

"The more the industry is sharing best practices and companies are

learning from each other, the better the outcomes will be for

people."

The funding let Lead Stories increase hiring. It now has 10

full-time employees and six part-time fact checkers, mostly former

CNN employees. Mr. Duke said it pays "on par" with the network's

six-figure salaries in some instances.

Facebook funds about half of the international publishers and

fact-checking organizations that are part of a coronavirus-specific

fact-checking alliance coordinated by the Poynter Institute's

International Fact-Checking Network.

"We were here before Facebook started working with us," said

Cristina Tardáguila, the IFCN's associate director, of the fact

checkers. "But there is no other program like this."

That might change. In January, video-sharing app TikTok said it

would begin reviewing user reports of misinformation with a

U.S.-based moderation staff, and that it was working with

third-party groups.

A reporter, editor, producer and special-projects manager at CNN

for 26 years, Mr. Duke was doing celebrity-focused profiles and

investigations out in Los Angeles when he resigned in 2014. He

spent five months working for the National Enquirer's parent

company before quitting to co-found Lead Stories.

The work can be rough, Mr. Duke said, with one employee quitting

after learning about the frequency that Lead Stories' reporters and

editors have received threats from people they fact check.

Staffers consult public-health guidance and identify entities

with expertise or firsthand knowledge about specific rumors. To

debunk the meme about free pandemic-time baby formula, for example,

Lead Stories reporters spoke with numerous manufacturers.

The company reviews a tiny fraction of the billions of

social-media posts produced each day. It uses a tool built by Mr.

Schenk, called Trendolizer, that tracks posts on the cusp of

spreading rapidly. Facebook also gives its fact-checking partners a

queue of posts that are suspicious or have already been flagged by

users.

Lead Stories' traffic is up nearly 10-fold, Mr. Duke said, with

about 8,000 users reading its reviews at any given time -- a number

that reflects how Facebook slows the spread of posts that it labels

as inaccurate.

Write to Jeff Horwitz at Jeff.Horwitz@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 30, 2020 11:14 ET (15:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

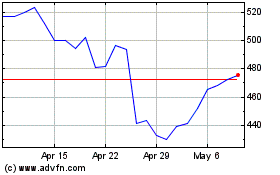

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024