By Christopher Mims

In a sometimes-heated hearing in Washington last April, 55 U.S.

representatives questioned Facebook Inc. Chief Executive Mark

Zuckerberg about privacy concerns and leaked user data. In the week

before the U.S. midterm elections, about two-thirds of those same

representatives are spending campaign dollars advertising on

Facebook.

Politicians' enthusiasm for targeting potential voters and

donors on Facebook cuts across party lines -- as did their

criticisms. Paul Tonko, a Democrat, told Mr. Zuckerberg at the

time, "Users trusted Facebook to prioritize user privacy and data

security, and that trust has been shattered." Republican Tim

Walberg expressed concern that Facebook was banning political

content and advertising based on the views expressed in it.

Campaigns for both have subsequently sunk money into Facebook

advertising, according to a tool Facebook recently released that

allows anyone to look up ads for political campaigns and "issues of

national importance." Neither congressman's campaign replied to

requests for comment.

Rep. Greg Walden (R., Ore.), who ran the hearing before the

House Energy and Commerce Committee, has placed hundreds of ads on

Facebook since April, when Facebook's database of political

advertising begins. "Greg Walden reaches voters in Oregon's Second

District across all mediums. That includes connecting to voters

online, on social-media platforms, and via radio, television, and

print newspapers," says a spokesman for his campaign.

That few politicians feel they can escape the necessity of

advertising on Facebook is precisely why we need to contemplate its

ever-growing scale, revenue and power. The ramp-up in political

spending across Facebook's social networks, which also include

Instagram, is breathtaking: In 2014, digital ad spending was 1% of

all political ad spending. Now it's 22%, or about $1.9 billion,

according to the nonpartisan Center for Responsive Politics.

Facebook says that politicians have spent nearly $300 million in

the U.S. on Facebook ads since May. As of Oct. 30, Democrats were

outspending Republicans on Facebook 3 to 1.

Politicians who want to reach the same voters their competitors

are reaching on Facebook have little choice but to go there, too.

That's despite mounting criticism that Facebook's algorithms are

actually driving increased political polarization and concerns that

the site serves as a vector for influence campaigns by Russia and

now Iran. Facebook, a driver of our fractious political debate, can

be seen as profiting from the fallout.

Giving Facebook money to target voters has become a

collective-action problem, much like campaign-finance sore spots:

Politicians on both sides of the aisle may wish to reduce the

influence of Facebook in U.S. elections, but few are incentivized

to act on that wish.

Targeting Voters

In the last midterm election season, sophisticated targeting

with online ads was mostly limited to national campaigns, says

Chris Massicotte, chief operating officer DSPolitical, an

ad-targeting firm that works with progressive candidates and says

it has targeted over 2.5 million ads since 2011. As such firms have

proliferated, the cost of this kind of online advertising has

dropped and the technology has moved down ballot. "Most of our

clients are state legislative campaigns and city council races," he

adds.

Facebook's targeting isn't just about its own huge trove of data

-- although that helps. Campaigns and their consultants collect

information about us from multiple data brokers, donor and mailing

lists, voter registration logs and other sources of publicly

available (or purchasable) information. Advertisers, political or

not, can match their databases with our real identities to serve us

a message.

"If I want Democrats who voted in the last two out of four

general elections who are over the age of 55 and are women, that's

something readily available in voter files," says Mr.

Massicotte.

Facebook is also very useful for testing political messages.

Campaigns can try out a message the way marketers float new brands

on Instagram, getting near-instant feedback on what works and what

doesn't. Those messages can subsequently be pushed out to other

mediums, says Mr. Massicotte.

And as regional races gain national attention, candidates can

leverage the power of Facebook to target donors outside of their

district or state.

Tracking Voters

During the April House hearing, Rep. Debbie Dingell, (D., Mich.)

told Mr. Zuckerberg, "You don't even know all the kinds of

information Facebook is collecting from its own users." Pressing

him further, she asked how many Facebook Pixels there are across

the web. (Facebook Pixel is a piece of code that websites embed

that lets Facebook track its users as they traverse the web.)

Her campaign website doesn't use Facebook Pixel. Instead, it

uses a different tracking pixel, from technology company NGP VAN.

The firm also allows campaigns to integrate data about voters with

Facebook's ad network. And Rep. Dingell's campaign has purchased

multiple ads on Facebook since April. Rep. Dingell's campaign

didn't reply to a request for comment.

Among the House members who questioned Mr. Zuckerberg, four

aren't currently running for office, and one doesn't have a

campaign website. Among the remaining 50, 44 have at least one form

of tracker on their campaign websites -- and 29 have the Facebook

Pixel tracker, according to Chandler Givens, chief executive of

data privacy firm TrackOff, which analyzed the sites for The Wall

Street Journal.

"That's how they know who to track via Facebook ads -- by

collecting our data without our knowledge and using it to influence

the content we see, " he says.

Not on Facebook

While advertising on Facebook appears to be the norm this

midterm season, there are those who have yet to buy ads on the

service. It's not necessarily conscientious objection to Facebook:

Perhaps an incumbent in a safe seat doesn't want to spend the

money; perhaps a candidate still sees better results from TV or

radio, or just isn't up-to-date on digital advertising.

Of House members who questioned Mr. Zuckerberg, Reps. Michael

Burgess, Kathy Castor and Bobby Rush are all running for

re-election this year but, according to Facebook's ad database,

have not bought ads on the platform. All have overwhelming odds of

winning their respective elections, according to the

election-prediction site FiveThirtyEight.

Politicians who aren't on Facebook are ceding voters' attention

to their opponents, says P.W. Singer, co-author of the book

"LikeWar," which argues that Facebook has become another front in a

global cyber conflict.

"It's both a battlespace and a marketplace," says Mr. Singer.

The result is an arms race between politicians who must spend to

get their message in front of potential voters and donors.

All of this lines up nicely with Facebook's profit motive. In

the company's most recent quarterly report, the number of monthly

active Facebook users in the U.S. and Europe was flat, but revenue

per user went up significantly. As advertisers, be they politicians

or merchants, become more sophisticated about using Facebook to

micro-target shoppers and voters, Facebook will continue to

profit.

-- For more WSJ Technology analysis, reviews, advice and

headlines, sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Write to Christopher Mims at christopher.mims@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

November 02, 2018 11:28 ET (15:28 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

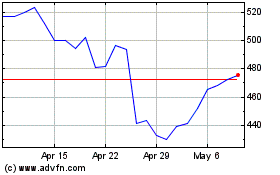

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024