By Christopher Mims

To achieve the dream of autonomous vehicles and robots, it's

going to take much more than computer vision and artificial

intelligence. Cars, drones, delivery bots, even our vacuum cleaners

and robot chefs are going to need something that our ancestors

developed millions of years ago: a sense of place.

"I definitely don't think people understand how reliant

autonomous cars are on the fidelity of the map," says Mary

Cummings, a professor of mechanical, electrical and computer

engineering at Duke University. "If the map is wrong then the car

is going to do something wrong."

It turns out that, whether it's Waymo's self-driving cars or the

many auto manufacturers relying on tech from Intel Corp.'s

Mobileye, so-called "autonomous" vehicles are cheating, in a way.

This is also true of models that are already commercially

available, such as Cadillacs with Super Cruise.

Rather than perceiving the world and deciding on the fly what to

do next, these autonomous and semi-autonomous vehicles are

comparing their glimpses of the world with a map stored in memory.

The incredibly detailed maps they rely on are what engineers call a

"world model" of the environment. The model contains things that

don't change very often, from the edges of roads and lanes to the

placement of stop signs, signals, crosswalks and other

infrastructure.

That self-driving cars -- and eventually, all other forms of

autonomous robots -- require such a map has big implications for

who will need to partner with whom in the autonomous driving space.

It implies a great deal of collaboration, or at least licensing,

because the amount of data and engineering required to build these

maps is so gargantuan. It means that, at least for the foreseeable

future, no matter how sophisticated a company's self-driving

technology, it must engage in a massive effort or else partner with

someone capable of making an ultra-detailed map of every road on

which they might drive -- companies like Ushr, TomTom and Here.

In urban environments where global positioning systems can be

inaccurate, a vehicle must navigate by landmarks, says Sam

Abuelsamid, a senior analyst with Navigant research who specializes

in mobility. Once a vehicle is navigating using lidar -- a 3-D

laser view of the environment -- along with cameras and possibly

radar, it can cross-reference certain buildings, lamp posts or

street markings, to identify its stretch of the road down to the

centimeter, he adds.

When the car knows precisely where it is, it can follow

predetermined routes in its memory, simplifying the driving

process. When the Super Cruise system is activated in a Cadillac,

the car stays in its lane by following a route that has been

determined ahead of time, says Christopher Thibodeau, senior vice

president and general manager at Ushr. Ushr makes the Super Cruise

system's maps -- terabytes of map data boiled down to a few hundred

megabytes of relevant route information.

It's not quite as if the car is driving on rails, but it's

close. Mr. Thibodeau says it allows the AI in the car to

concentrate only on the things in its environment that are

changing: cars, pedestrians, unexpected obstacles, construction and

the like.

This is especially important because self-driving is already a

difficult problem both in terms of the number of sensors it

requires and the amount of computing power. A typical fully

autonomous self-driving car is drawing 2,000 to 4,000 extra watts

of power from its electrical system to operate all of its sensors

and computers, Mr. Abuelsamid says.

The car must combine data coming from a variety of sensors -- a

problem called "sensor fusion" that is an area of intense research

-- into a single consensus view of reality.

If something goes wrong, the consequences can be dire. Uber

Technologies Inc.'s self-driving car killed a pedestrian in March,

and more than one Tesla has crashed into the back of a stopped fire

truck at highway speeds, apparently while its Autopilot

driver-assistance system was on.

Before autonomous vehicles can truly be trusted to operate

without human supervision, the computers tasked with driving

according to those maps while looking out for unexpected hazards

must be much more powerful than those in use today, says Mr.

Abuelsamid. Self-driving chips from both Nvidia Corp. and Mobileye

are undergoing rapid leaps in computing power, on the order of a

tenfold improvement every time these firms release a new

iteration.

For Nvidia and Mobileye-owner Intel, this means new

opportunities to enter a market that has long been dominated by

specialist manufacturers of automotive-grade microchips, such as

NXP Semiconductors NV, Mr. Abuelsamid says. But it could also hurt

companies that were early to the race to autonomy, such as Tesla

Inc.

"Frankly both the sensing and compute capabilities that [Tesla's

vehicles] have today are not capable of providing full self-driving

under all conditions, which is what [Chief Executive Elon Musk]

said they could do," says Mr. Abuelsamid. That might change. Mr.

Musk has said that Tesla is developing its own AI chip for

self-driving, and that it will be a "drop-in" replacement for the

existing hardware in its cars. It's not clear when this replacement

computer for Tesla vehicles will arrive.

Eventually, Dr. Cummings says, the hope is that all self-driving

vehicles will contribute to a collective database that updates in

near real-time as roads and conditions change. Mobileye has already

promised to create such a database with camera data coming from its

partners, including Nissan Motor Co., Volkswagen AG and BMW AG.

By the end of 2018, Mobileye will be gathering data from three

million vehicles' forward-facing cameras, which will be compiled

into a database that will be usable for driver assist and

self-driving systems starting in 2019, says Jack Weast, vice

president of autonomous vehicle standards at Mobileye.

Others, such as Waymo, are apparently trying to go it alone,

since data and algorithms are a huge competitive advantage in the

race to fully autonomous driving.

But the cost of such precision mapping sensors at the moment is

very high, says Mr. Thibodeau, adding at least $100,000 to the

price of each vehicle. These systems will become cheaper, but he

believes it will be at least three to five years before they make

it onto the kind of vehicles that private citizens could buy, and

that it will take many years after that for them to achieve

sufficient density on the world's roadways to contribute to

detailed maps suitable for autonomous driving.

How often we re-map all our roads is of critical importance.

Ushr's current database covers about 200,000 miles of

controlled-access highways in North America, and even so, the

amount of roadway that changes in that database is between 6,000

and 8,000 miles a year, says Mr. Thibodeau.

Another challenge for such a system, says Dr. Cummings, is that

any central database used by autonomous vehicles would be a prime

target for hackers. Not only would a breach have dire consequences,

but so would corrupting the map from the outside -- in other words,

attempting to fool autonomous vehicles by changing things in their

environment.

That maps are so critical to self-driving shows, once again,

that the road to fully autonomous fleets is longer than we were

told -- and pushes back the arrival of self-driving cars even

further.

Write to Christopher Mims at christopher.mims@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 11, 2018 08:15 ET (12:15 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

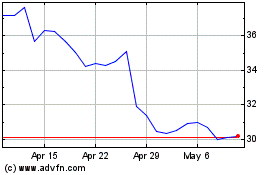

Intel (NASDAQ:INTC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

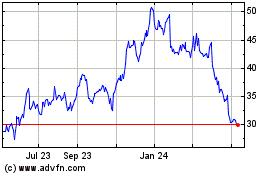

Intel (NASDAQ:INTC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024