Is Tesla or Exxon More Sustainable? It Depends Whom You Ask

September 17 2018 - 12:28PM

Dow Jones News

By James Mackintosh

Is Elon Musk's electric-car maker Tesla the best, the worst or a

merely middling performer on environmental issues? Is Warren

Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway one of the worst-governed big U.S.

companies? Is General Motors one of the most socially aware

businesses, or one of the least?

Investors picking a scoring system for ESG -- environmental,

social and governance -- issues facing companies can have any of

those outcomes.

The differences are easy enough to understand if you dig into

the details. Yet, they show just how difficult it is to take a

simple approach to ESG investing, a style that is becoming

ever-more popular. In addition to the billions of dollars of

exchange-traded funds based on ESG indexes, increasingly fund

managers are being pushed to produce portfolios with better ESG

ratings, encouraged by public mutual-fund ESG scores.

The problem here isn't the ESG ratings, but that they are used

as though they were some sort of objective truth. In reality they

are no more than a series of judgments by the scoring companies

about what matters -- and investors who blindly follow their scores

are buying into those opinions, mostly without even knowing what

they are.

To illustrate these differences, we can dig into the scores

given to five big companies by FTSE Russell, MSCI and

Sustainalytics, all used for ESG indexes and by institutional

investors. The companies are Tesla, Berkshire, oil major Exxon

Mobil, Google-owner Alphabet and carmaker General Motors.

Perhaps the biggest surprise is Tesla, ranked by MSCI at the top

of the industry, and by FTSE as the worst carmaker globally on ESG

issues. Sustainalytics puts it in the middle.

The explanation comes down to what is measured, and how the

measurement is affected by disclosure.

MSCI gives Tesla a near-perfect score for environment, because

it has selected two themes as the most important for the car

industry: the carbon produced by its products, and the

opportunities the company has in clean technology.

FTSE gives Tesla a "zero" on environment, because its scores

ignore emissions from its cars, rating only emissions from its

factories (to confuse things further, FTSE's separate "Green

revenue" score gives Tesla 100%).

Tesla highlights another major difference in scoring: what to do

when a company doesn't disclose. FTSE says it has to assume the

worst if no information is provided about issues that matter to a

company -- and that giving it the worst score encourages more

disclosure.

Tesla, which discloses little about its operations compared with

other automakers, suffers from FTSE's approach, particularly on

social issues (where all three graders anyway give it low scores on

how it treats workers). MSCI is more generous, assuming that if

there's no disclosure the company operates in line with regional

and industry norms. Sustainalytics declined to explain its

methodology, but it gives points for disclosure of policies --

again, Tesla suffers -- as well as low scores for issues where

there is too little disclosure to calculate, such as Tesla's

renewable-energy use.

Berkshire suffers on disclosure too, again being zeroed by FTSE

on both environment and social scores.

Another problem is how to put the separate environmental, social

and governance scores together. Should a highly polluting company

be able to offset that by having great governance and treating

workers well? Sustainalytics ranks Exxon top of the five companies

overall, because it puts a 40% weight on social issues, where Exxon

does well thanks to strong policies for its workers, supply chain

and local communities. MSCI ranks Exxon fourth of the five in part

because it puts a 51% weight on environment and only 17% on social

issues.

The three create their scores differently, too. MSCI selects --

using rules -- a small number of factors that matter to each

company, making each important to the overall score. FTSE includes

a broader set of factors, but is still rules-based. Sustainalytics

also has a broad set of factors, and uses analyst judgments for

some of its assessments. In all three cases the design of the rules

and scoring system makes a big difference to the outcome.

And sometimes the assessments simply differ. MSCI puts Alphabet

in the bottom quartile of its industry for the subcategory of

corporate governance thanks to controlling shareholders and

related-party transactions, although its overall governance score

is lifted by a strong score on "corruption and instability" issues.

FTSE takes the opposite approach, putting Alphabet in the top half

of its peer group for governance, and says it is held back in part

by a weak score for anticorruption assessments and training, as

well as tax disclosure.x`

Investors should not treat ESG scores as settled facts to be

used on their own, but as potentially worthwhile analysis that

needs to be understood before being acted on. The thick ESG reports

behind the scores offer useful detail about the policies and

controversies around each business. But just as with financial

accounts, investing without understanding is unlikely to deliver

what you want.

Write to James Mackintosh at James.Mackintosh@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 17, 2018 12:13 ET (16:13 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

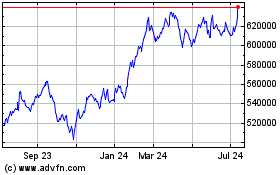

Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE:BRK.A)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

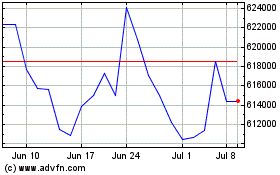

Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE:BRK.A)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024