Investors grow leery of free-spending firms, preferring the

discipline seen at ConocoPhillips

By Bradley Olson

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (April 3, 2018).

Big oil is starting to think small.

Once defined by massive spending and ambitious exploration, some

of the world's biggest energy companies have begun to preach

frugality. Investors increasingly favor producers that promise to

increase cash payouts, rather than boosting spending to drill for

more oil.

The best-performing major U.S. oil producer by share price

increase in the past year isn't Exxon Mobil Corp. or Chevron Corp.,

but ConocoPhillips, a company that has reduced its size and

prioritized share buybacks and dividends over growth in recent

years. Its shares have risen 29%, beating the S&P 500 and

significantly outperforming the company's U.S. rivals. Shares of

Exxon, which recently laid out plans to increase spending by 25% or

more beginning in 2020, have fallen by about 9% in that time.

The success of ConocoPhillips suggests that investors are

looking for something different from big oil companies these days.

Fading are the days when shareholders bought Exxon or Chevron to

get exposure to the big profits that could come with rising oil

prices, while being insulated somewhat from falling prices through

running refineries and petrochemical plants.

An increasing number of investors want conservative, stable

returns -- not unlike why some look to the utility industry.

"The oil-and-gas industry is on its way to transitioning to a

more mature market in the U.S.," said Tim Beranek, who helps manage

more than $18 billion in assets for Cambiar Investors. "Over the

last decade, with the evolution of shale, it was an emerging

industry and attracted a lot of growth investors. Now, the

shareholder base just wants return on capital."

As surging U.S. crude production continues to threaten price

rallies with new supply, investors have become far more skeptical

about growth. Instead, the push for cash is catching on.

Beginning in 2012, ConocoPhillips, once among the world's

biggest oil companies, started to make this transition. It spun off

its refining business, closed its deepwater exploration unit, and

chose to distribute more of its free cash flow to shareholders

rather than reinvesting it.

Few oil chieftains at the time were moving in that direction. It

was "a pretty lonely place," said Ryan Lance, ConocoPhillips' chief

executive, in an interview.

The strategy was shaped by a view that surging U.S. oil output

would create a new era of uncertainty. American oil production

recently topped 10 million barrels a day, breaking a prior U.S.

record set in 1970.

"The cycles are getting shorter, from peak to peak and trough to

trough, " Mr. Lance said. Instead of "chasing the cycles up and

down," he said, ConocoPhillips has focused on its "sustaining

capital" -- the oil price it needs to keep production flat and pay

for dividends and new investments.

The company's "sustaining" price is now $40 a barrel, Mr. Lance

said, which means that with U.S. crude selling for more than $60 a

barrel, much of the excess can go to shareholders.

While other companies have boosted share buybacks and dividends,

few have as low a sustaining price. Many are turning to asset sales

in order to balance new spending and cash-return plans with the

funds they receive from operations. For example, Hess Corp.

increased its buyback program by $1 billion in March, avoiding a

proxy fight with an activist shareholder.

The company is expected to generate about $1.6 billion from

operations, according to analyst estimates on FactSet. With $2.1

billion in spending planned for 2018, that equates to a cash

deficit of $1.5 billion. Hess sold more than $3 billion in assets

last year. Hess executives have said they plan to reach a point

where they will generate enough cash to pay for new investments by

2020.

Exxon and Chevron, which are much larger than ConocoPhillips and

have far higher profits, also have longstanding dividends that

neither company cut since oil plunged in 2014. The companies also

had a long history of buying back billions of dollars of their

shares, but Chevron suspended its program in 2015 and Exxon's was

scaled back significantly. Chevron is expected to resume its

buyback program soon.

The recent run of ConocoPhillips hasn't been without challenges.

Once among the industry's biggest dividend payers, the company cut

the payout by about two-thirds in early 2016 as oil prices fell to

less than $30 a barrel. It argues that this is all part of its

cash-management strategy. While oil prices rise, it returns the

bounty to investors, but when prices fall below the sustaining

price, it can sell assets, cut dividends or increase debt.

Crude prices are up by about 26% in the past six months, but

unlike in the past, oil equities haven't followed, suggesting that

some investors lack confidence in the price rally.

In this climate, shareholders are likely to prefer producers

like ConocoPhillips that demonstrate frugality, said Doug Terreson,

an energy analyst at Evercore ISI who has championed greater

discipline in oil.

"One of the key concerns in the industry is that companies are

growing more disciplined today, but if the oil price rises, they

will increase spending," he said.

Write to Bradley Olson at Bradley.Olson@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 03, 2018 02:47 ET (06:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

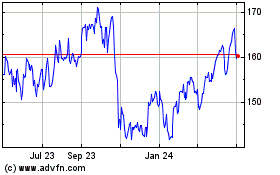

Chevron (NYSE:CVX)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

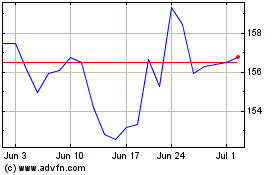

Chevron (NYSE:CVX)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024