Approach to policing those with access to user information led

to company's crisis

By Deepa Seetharaman and Kirsten Grind

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (March 21, 2018).

Facebook Inc.'s loose approach to policing how app creators and

others deployed its user data persisted for years, including after

a 2015 effort by the social network to restrict access, according

to court documents and people familiar with Facebook. The

social-media giant is now dealing with the fallout.

The Federal Trade Commission is investigating whether Facebook

violated terms of a 2011 settlement when data of up to 50 million

users was transferred to an analytics firm tied to President Donald

Trump's campaign, a person familiar with the matter said on

Tuesday. If the FTC finds that Facebook violated the settlement

terms, the company could face millions of dollars in fines.

That firm, Cambridge Analytica, said Tuesday it is launching its

own investigation to determine if the company engaged in any

wrongdoing. In addition, it said it was suspending its chief

executive, Alexander Nix, after a video released Monday depicted

Mr. Nix touting campaign tactics such as entrapping political

opponents with bribes and sex. A spokesman said the comments by Mr.

Nix in the video "do not represent the values or operations of the

firm, and his suspension reflects the seriousness with which we

view this violation."

Meanwhile, Canada's privacy commissioner said Tuesday it had

formally opened its own investigation into alleged unauthorized

access and use of Facebook user profiles, focusing on the company's

compliance with Canada's privacy law.

The user-data controversy, which knocked another 2.6% off

Facebook's stock price Tuesday, after it fell 6.8% Monday,

underscores the broad challenge for Facebook: how to balance the

pursuit of digital advertising dollars, which depend on selling

access to user data, with protecting the privacy and personal data

of its more than two billion monthly users.

The Cambridge Analytica crisis has its roots in a 2007 decision

by Facebook to open access to its so-called social graph -- the web

of friend connections, "likes" and other Facebook activity that

knit users together.

While advertisers pay to reach Facebook's users, developers were

for years able to tap that data by creating an app that plugged

into Facebook's platform. Tens of thousands of app developers and

others used the data, giving birth to a new crop of dating and

job-search apps, as well a new form of political campaigning.

Although Facebook had rules stating the terms under which

developers could accumulate data, it appeared not to be able to

ensure its rules were being followed, developers and former

employees said. In interviews, developers said Facebook was

sometimes unclear about how they could use the data they gathered

from the platform.

"Their enforcement mechanism is, if they notice it, they tell

you to stop," says Nick Soman, founder and chief executive of the

health-care company Decent, who has accessed Facebook's data in the

past.

In 2010, The Wall Street Journal reported that online tracking

firm RapLeaf Inc. was using Facebook data to build databases of

personal user information and selling the data to political

advertisers and others, in some cases transmitting users' ID

numbers. At the time, RapLeaf said the transmission of the data was

inadvertent and stopped.

The episode prompted Facebook to build a way to tag a

developers' data so that if it leaked, the company could trace it

back to the source, according to a person familiar with the matter.

This analysis could only be done after Facebook was alerted to a

potential violation, the person said.

In 2011, Facebook users started complaining to the social

network that some of their old profile data was inexplicably posted

for anyone to view on a little-known search site called Profile

Engine, court records allege. Facebook sued the developer two years

later, saying it had violated its agreement, but not before the

details of about 420 million user profiles were collected,

according to the court records.

Early on, almost anyone could create a Facebook app and access a

trove of data about the site's users. President Barack Obama's 2012

re-election campaign, for example, created a voter-outreach app

that found other potential supporters among its users' connections

on Facebook by plugging directly into the company's platform.

In 2014, Facebook said it would restrict developers' access to

many data points about app users' friends, citing privacy concerns.

But even after the policy went into effect in 2015, Facebook

couldn't proactively keep track of how developers used previously

downloaded data, according to current and former employees. By

2016, Facebook had changed its platform rules, making it impossible

for other campaigns to do the same.

"On an ongoing basis, we also do a variety of manual and

automated checks to ensure compliance with our policies and a

positive experience for users," a Facebook spokesman said.

The Facebook data allegedly used by Cambridge Analytica was

provided by an academic who wasn't authorized to share the user

data under Facebook's policies. Cambridge Analytica has said it

didn't break Facebook's rules.

On Friday, Facebook said it learned about the academic sharing

the data in 2015 and demanded the parties delete the data. Facebook

said it learned this month the parties kept those records despite

saying the information had been destroyed.

Sandy Parakilas, a former Facebook platform-operations manager

from 2011 to 2012, said in an interview that Facebook was primarily

alerted to data-policy violations from media reports or companies

that said competing apps were breaking Facebook's rules.

According to Mr. Parakilas, a media report in 2011 said the

social-media startup Klout Inc. had created profiles for minors

without their knowledge using Facebook data. Klout quickly stopped

the practice after the report, Mr. Parakilas said.

Soon after, Mr. Parakilas said, he called Klout's management

team to ask if the startup was violating Facebook's data policies.

Klout officials denied it violated the policies, Mr. Parakilas

said, and he asked the company to make it sure it wasn't violating

the policies in the future.

"And that was it. They continued to access the platform," Mr.

Parakilas said in an interview. "We never got to the answer of what

happened."

He added: "The main enforcement mechanism was call them and yell

at them."

Klout couldn't be immediately reached for comment.

Facebook in 2015 rolled out new restrictions to the type of data

outside parties could access, making it harder for them in

particular to get data on a user's friend base. Developers and

other parties were informed of the change through an email.

But Facebook didn't instruct developers to delete the data they

had already captured, nor did it follow up to see if developers

were still using it, according to some developers.

--Jim Oberman and John D. McKinnon contributed to this

article.

Write to Deepa Seetharaman at Deepa.Seetharaman@wsj.com and

Kirsten Grind at kirsten.grind@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 21, 2018 02:47 ET (06:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

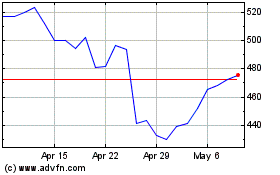

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024