By Liz Hoffman

David Solomon became the heir apparent at Goldman Sachs Group

Inc. Monday after his main rival for the top job abruptly resigned,

moves that show the Wall Street powerhouse is continuing to move

beyond its trading roots.

The surprise announcement came after Goldman's board of

directors last month anointed Mr. Solomon as the eventual successor

to current CEO Lloyd Blankfein, according to people familiar with

the matter.

The Wall Street Journal reported last week that Mr. Blankfein

could retire as soon as year-end, though he remains firmly in

control of his exit. Messrs. Schwartz, 54, and Solomon, 56, who

were jointly elevated to the No. 2 role in December 2016, were the

top contenders to succeed him.

The two hail from different parts of the firm. Mr. Solomon is a

longtime investment banker who DJs on the side. Mr. Schwartz, a

karate black belt, scaled the ranks of Goldman's trading arm on his

way to becoming CFO.

In choosing Mr. Solomon, Goldman is going with a business

builder who is respected, if not universally loved, inside the

firm. The move amounts to a bet that the coming decade will look

little like the last one, as Goldman continues to evolve from a

secretive trading powerhouse into a more entrepreneurial place.

The two men were told of the board's decision last week, at

which point Mr. Schwartz, who was informed upon his return from a

West Coast trip, said he would leave, people familiar with the

matter said.

Mr. Blankfein shared the news Monday morning with the firm's

management committee, a group of about 35 top officials. "Harvey's

leaving the firm, " the typically blunt CEO said, according to

people briefed on the meeting. Mr. Solomon quickly canceled a

planned trip to China.

For generations, power at Goldman has tended to swing from

bankers to traders. When Mr. Blankfein, a former trading chief,

took over in 2006, that business was dominant. Since the financial

crisis, though, it has faltered, sending Goldman into new

businesses like consumer banking and low-fee index funds in search

of growth.

Those changes were seen to favor Mr. Solomon. He know known less

as a superstar deal maker than a strong manager, able to prune dead

weight, motivate strivers and marshal Goldman's resources behind

big initiatives.

"David is a pied piper, and I mean that in the best way," said

Chris Nassetta, CEO of Hilton Hotels Corp., who worked with Mr.

Solomon at Bear Stearns. "People want to follow him."

Mr. Solomon came to Wall Street in the mid-1980s, selling

commercial paper at Drexel Burnham Lambert. Off duty, he played

social planner to a group of college friends, organizing casino

outings in Atlantic City and summer rentals in the Hamptons, where

roommates would wake up to find him mowing the lawn.

After a stint at Bear Stearns, Mr. Solomon joined Goldman as a

rare outside partner in 1999 and set about to build a junk-debt

business. In 2006 he assumed responsibility for Goldman's

investment bankers, who advise companies on mergers and

fundraisings.

Mr. Solomon is credited with professionalizing that division,

which he ran for a decade. The unit's profit margin doubled, even

as some longtime bankers lamented the decline of collegiality and

autonomy.

He had a policy of giving zero bonuses to the bottom 5% of

employees, executives said. But he also spearheaded Goldman's

efforts to lighten the workload for junior bankers, and took a

leading role in the firm's effort to recruit and promote women. He

built a debt capital-markets business that reported record revenues

last year.

Mr. Schwartz, meanwhile, embodied Goldman's profitable past,

having scaled the ranks of its trading division. As finance chief

from 2013 to 2016, Mr. Schwartz navigated the political and market

forces that reshaped banking after the crisis, and was a strong

hand in the areas of risk management and regulation.

He graduated from high school in New Jersey with grades so poor

he didn't bother applying to college. He eventually attended

Rutgers University, working as nightclub bouncer and other odd jobs

to pay his way, and joined Citigroup Inc. as an operations temp in

1989.

He came to Goldman's commodities trading arm in 1997 as a

derivatives salesman, helping energy and mining companies protect

themselves from price swings.

By 2008, Mr. Schwartz was running the trading division. As the

financial crisis unfolded, he kept the firm on the offensive while

competitors pulled back. The gambit worked: Goldman's traders made

$33 billion in 2009, the most profitable year on record for a Wall

Street broker-dealer.

Mr. Schwartz was named CFO four years later, a move was so

unexpected that senior executives including the firm's heads of

risk and accounting threatened to quit, according to a person

familiar with the matter.

But Mr. Schwartz won over critics by overseeing an operation

that avoided surprises that plagued other banks. His 18-quarter

tenure as CFO is captured in pen on a pair of lime-green boxing

gloves that he keeps in his office: "18-0, all by KO."

Write to Liz Hoffman at liz.hoffman@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 12, 2018 17:33 ET (21:33 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

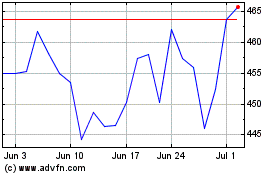

Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

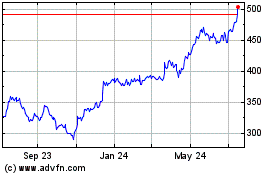

Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024