By Georgia Wells and Deepa Seetharaman

Two accounts that Facebook Inc. said appear to have ties to

Russian operatives amassed more than half a million followers in

the past couple of years with posts, ads and events that stoked

strong emotions over issues including race and immigration.

Most followers never suspected that people with possible Russian

ties were behind the accounts -- except for a few users who

interacted in real life with the people running the sites.

Some users said the content from these accounts seemed like

something their peers would share. "Blacktivist," an account that

supported causes in the black community and used hashtags such as

#BlackLivesMatter, frequently posted videos of police allegedly

shooting unarmed black men. "Secured Borders" often railed against

illegal immigration, publishing material such as a photoshopped

image of a woman holding a sign that said "Give me more free

shit!"

Via several platforms -- Facebook and its Messenger and

Instagram services, as well as Twitter Inc. and YouTube, part of

Alphabet Inc.'s Google -- 470 Russia-backed Facebook accounts

including Blacktivist and Secured Borders quietly infiltrated

communities on social media. The issues they targeted spanned the

U.S. political and social spectrum, including religion, race,

immigration, gun rights and gay rights. Facebook said the accounts

were created by Russian entities to exploit tensions among

Americans and interfere with U.S. elections.

"We were clear that there was a possibility that

less-than-friendly actors would look for ways to align with the

movement," said Heber Brown III, a pastor and activist for racial

justice in Baltimore who first noticed the Blacktivist group on

Twitter in April 2016. "But I had no idea that it would reach all

the way to the Kremlin."

Russia has denied any interference in the election.

The experiences of Facebook users illustrate the apparent

sophistication of people who ran the accounts. The posts mimicked

the tone and topics of conversations in various communities well

enough that the accounts largely were believed to be authentic.

In late August, before it was taken down, Blacktivist had

411,000 followers, according to cached versions of the page,

surpassing the official "Black Lives Matter" Facebook account by

more than 100,000 users.

Facebook disclosed last month that the Internet Research Agency,

a Russian outfit that shares pro-Kremlin views online, created

accounts that bought $100,000 in ads over a two-year period, from

June 2015 to May 2017. At least some of them continued to post

divisive content as recently as August.

"Any time there's abuse on our system, foreign interference on

our system, we are upset," Facebook Chief Operating Officer Sheryl

Sandberg said at an event on Thursday. "But what we really owe the

American people is determination. These are threats. These are

challenges, but we will do everything we can to defeat them because

our values are worth defending." Facebook has declined to say how

many users engaged with the Russian content overall.

The Journal interviewed about a dozen people who followed the

pages to illustrate how the accounts attracted so many users. Most

of the people the Journal interviewed said they don't believe the

content they absorbed sowed divisions or influenced their voting

choices. "No Russian ever called me and said, 'Who are you going to

vote for?'" said Wendy Harris, from Frisco, Texas, who said she

thinks she followed the "Secured Borders" page around the time of

the election. "I do my own research."

Facebook removed the 470 accounts last month for violating its

policy prohibiting accounts from misrepresenting their origin. But

because they weren't identified earlier, and because of an

algorithm that favors posts that trigger reactions regardless of

their authenticity, these groups were able to operate and amass a

following for the past two years or longer.

In interviews, Facebook users often said they couldn't remember

the first time they followed one of these pages. Facebook said the

entities used divisive ads to lure users to their pages, where the

accounts would then serve up unpaid content -- in the form of

posts, photos and videos -- more frequently. Soon the content

filled their newsfeeds, the users said.

One Facebook user in Charlotte, N.C., recalled coming across the

Blacktivist page in late 2014 after a friend shared a Blacktivist

post about the FBI's surveillance of black activists. Soon after,

the person, who declined to be named, shared a different

Blacktivist post that elicited a flood of likes and comments from

the person's friends, potentially drawing more people into

Blacktivist's network. "Whoever wrote that copy definitely had

their finger on the pulse," the person said.

Sometimes the Blacktivist page shared content that came from a

page with a more militant stance called "The Quiet Ri0t," which

published content including an image that said "Black revenge:

white people fear it...But so do most black people." That site is

no longer up and no contact information is listed.

Blacktivist also used Facebook Messenger, the messaging service

spinoff of Facebook, to reach people such as M'tep Merlotte, from

Washington, D.C., who received an invite from the group before the

election. Soon, she was receiving videos, including alleged police

brutality, with a comment about where they happened and what they

meant for black Americans.

The group posted nearly every day so Ms. Merlotte turned off

Messenger notifications. "It was irritating," she said.

Blacktivist began raising suspicion among some followers when

the account tried to organize real-life events. The account planned

several events last year in cities such as Chicago, Baltimore,

Houston and Atlanta, according to archived versions of

webpages.

A march planned for April 2016 in Baltimore to mark the

anniversary of the death of Freddie Gray, a black man who suffered

injuries and died while in the custody of the Baltimore Police

Department, spurred local activists to contact the Blacktivist

administrators about the difficulty of having a group from out of

town organize a sensitive event.

Cortly Witherspoon, a Baltimore-area activist who spoke to one

of the administrators by phone, said he was surprised to hear him

speak with an accent Mr. Witherspoon identified as possibly

European.

Around the same time, Rev. Brown, the Baltimore pastor, also

realized Blacktivist's administrators weren't from his area. He

messaged Blacktivist on Twitter and asked if Blacktivist was a

local organizer because none of his activist acquaintances had

heard of the group.

"Me personally -- no," the administrator for the Blacktivist

account replied, according to a screenshot of the exchange viewed

by The Wall Street Journal. "We are looking for friendship, because

we are fighting for the same reasons."

--Jim Oberman contributed to this article.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 13, 2017 14:32 ET (18:32 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2017 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

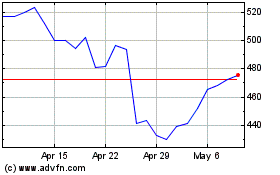

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024